- Can you identify the social statuses found in the biography in the module introduction? Which would you describe as ascribed? Which ones are achieved? Why?

- Make a list of social statuses with which you identify. Which ones are achieved, and which ones ascribed? Why?

Sociology of Identity

Kritee Ahmed

Who Am I? How Did I Become Me?

.

My name is Kritee Ahmed.

I am a teacher, a student, a writer, and a researcher, as well as a husband, father, and son. I identify as Bengali, South Asian, and Muslim. I am Canadian-born, able-bodied, and come from a working-class background. I love to eat food, such as fresh-cut fries and fragrant, flavourful biryani; you might call me a foodie.

Is this me? How did I become this person? In this module, we grapple with these two questions by considering concepts and theories used in sociology. The processes that shape and define us are far more complex than we might imagine.

Constructing Identities

In my simple biography above, I identify myself using different categories. Before we make sense of those identities and where they come from, we must think through how identity is formed. There are two main frameworks used to understand identity: essentialism and social constructionism.

.

According to essentialism, identity is innate; it is something with which we are born. Essentialism proposes that we have some kind of unchanging fundamental self. Identity, thus, lies outside the sphere of culture and politics (O’Brien & Szeman, 2004, p. 170). Essentialism as a theory of identity limits the possibility of our identities changing or shifting over time. It suggests that from birth to death we can only identify in one way.

The other way of looking at identity is to see it as something that takes shape and changes over time. We might think of identity as cultural critic Stuart Hall (1990) does, as “not already an accomplished fact” but rather “a ‘production,’ which is never complete, always in process” (p. 395). This understanding of how identities are made up is called social constructionism.

Social constructionism argues that identity is the product of society and culture. It reminds us that our connections to each other, the social groups we are part of, and the social institutions we interact with all play a role in shaping our identity. In other words, our identities are produced, reproduced, and developed through our relationships with and within society. In this course, we focus on how our identities are constructed by understanding how society functions.

Go Deeper

Want to know more about cultural critic Stuart Hall who passed away in 2014? Read his obituary here. (Source: “Stuart Hall – Obituary,” 2014)

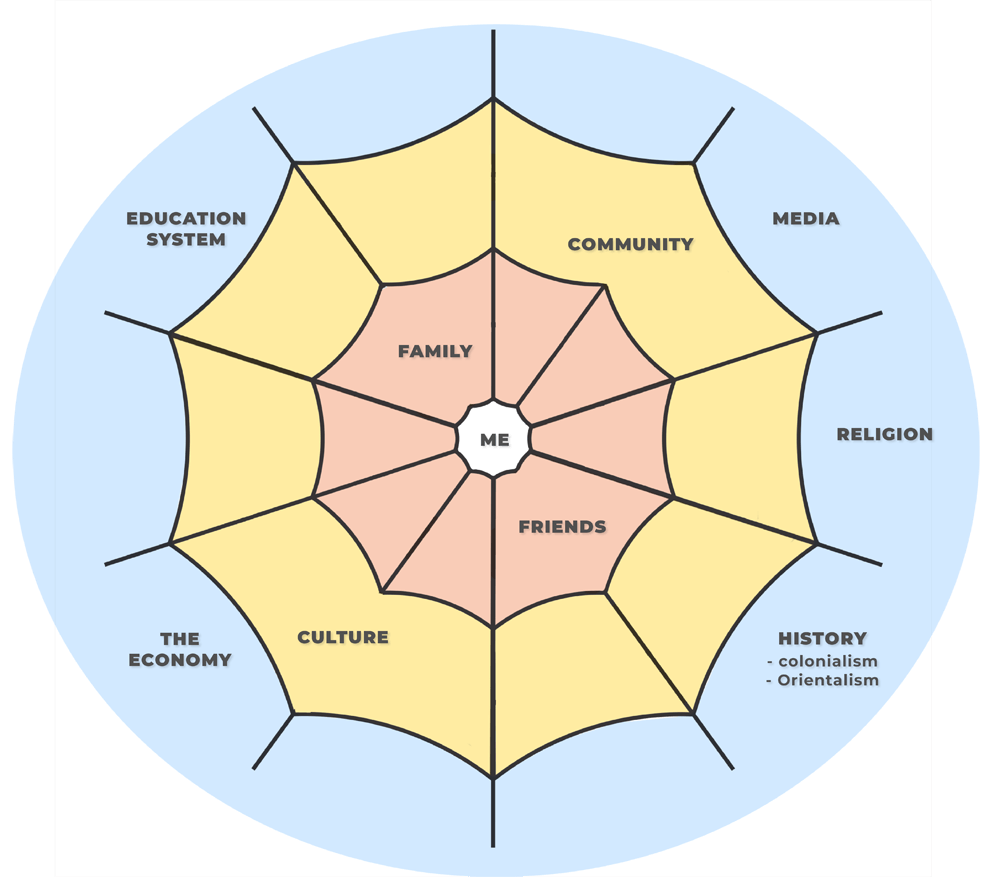

Societal Web

The question of identity is more complex than simply choosing the key details of how we present ourselves to others and the career choices we make. For example, not everyone can choose the career path they would like to take. It may be too expensive to follow that career path. It may take too long. It may require a move from one place to another, which might not be possible. Our decision might be affected by what others, including our loved ones, need. Look to the image title “Societal Web.” The societal web’s basic function is to get us to think about how we are connected to family and friends, community groups, social institutions, media, and history. By realizing how we are connected to one another, a key aspect of global citizenship, it reminds us of how our identities are also connected to not only the choices we make but to others who impact how we come to identify ourselves. By thinking through identity in relation to how we are connected to others, we can think of how our identities come to be shaped by social construction—through our relationships and connections, the groups we are a part of, culture, and social institutions such as media and government.

Identifying You and Me

When I talk about myself as a teacher, student, father, or Canadian, I am identifying myself through a social status. Social statuses help us categorize our identities through the positions we hold in society and how these positions relate to other positions in society (Murray et al., 2014, pp. 119–120). In other words, social statuses, rightly or wrongly, also tend to be arranged based on a hierarchy of prestige. For example, think of the health-care field and how the different professions within it relate to one another: volunteers, cleaners, pharmacists, technicians, nurses, doctors, administrators. All these workers are needed to keep us healthy, but how are these statuses valued differently based on prestige or ranked in terms of importance?

The duties associated with a social status are socially defined. This means that we don’t simply make them up on our own. Society helps to develop an understanding about those specific duties. We refer to the duties, or behavioural expectations, that are tied to social statuses as roles.

For example, think of a teacher you’ve had and consider the following questions:

- What were your behavioural expectations of the teacher before you met them?

- How did you expect them to speak and present themselves (e.g. how they dress, what they look like) to the class?

- How did those expectations affect your interactions with the teacher?

- From where did those expectations come, anyway?

Chances are these expectations come from ideas floating around in society (such as in media representations of those social statuses; see the module on Critical Media Literacy). By accepting these expectations as true and incorporating them in our interactions, we reinforce them.

We can roughly divide social statuses into two categories, though there may be overlap between these two categories. First, some social statuses are ascribed. This means they are assigned to us at birth and cannot be easily changed. Examples of these include your age, sex, or ethnicity. Second, some statuses are achieved. These require work and effort to earn and include our jobs or abilities. Our accomplishments, such as degrees or diplomas we complete, can help us earn these achieved statuses. When you think of the social status of teacher, is it an example of an ascribed or an achieved social status?

Choosing Who I Am

Imagine you’re trying to figure out what to wear to a job interview. Perhaps this choice feels simple to you. You know exactly what to wear. But when we slow down the process and think about what went into that decision—about who you are and how you want to present yourself— a more complex picture emerges.

George Herbert Mead helps us understand that process. He describes the self as having two key aspects, the “I” and the “me.” The “I” is the part of you that presents itself to and interacts with others. When it does this, it uses information it receives from the “me.” The “me” is like a library of past information collected from the interactions and experiences of the “I” (Elliot, 2014, p. 33; O’Brien, 2011, p. 110; Appelrouth & Desfor Edles, 2007, p. 179). The “I” and the “me” have internal conversations discussing how the “I” should act or behave (Dillon, 2010, p. 259). The “I” is also the creative aspect of you (Craib, 1992, p. 88), so it can, if it chooses, behave as it wants, despite the advice and data provided through conversations with the “me.”

This internal dialogue between the two aspects of the self is how we reflect on things. Reflection shapes who we are, and how we present ourselves. It allows us to think about and interpret the various roles we’re expected to play when performing certain social statuses. For example, in figuring out what to wear for a job interview, your “I” has a conversation with your “me” as they decide together how your “I” should present itself. The result of that conversation determines what you end up wearing. You may want to dress professionally or creatively (however you interpret that!) depending on the type of interview, and the social status and roles you want to present to the interviewer. In this way, Mead’s theory helps us to understand how our identity is shaped, and how our understanding of social statuses and roles comes to be.

Another sociologist, Charles Cooley, frames this a little differently. Cooley believes that we develop our sense of self, or self-identity, based on how we imagine others perceive or judge us. He calls this the looking-glass self (Murray et al., 2014, p. 102).

In the end, Mead and Cooley both highlight that our sense of self and our identity are shaped by forces around us. While we choose many aspects of identity, the range of choices that we have is affected by the people and things we’re connected to.

Do you remember a time when you sent an SMS/text or a WhatsApp message to a friend and you waited a long time for them to get back to you? What went through your mind in that time? Did it go something like this?

You send a text to your friend, telling them you want their response. They don’t respond right away like you expect them to. In fact, two hours pass, perhaps even a day, and you start to imagine what you may have done that’s keeping them from responding to you. Your mind races. You think back to interactions that may have caused your friend to be upset at you. You wonder how you’ve offended them. The longer you wait, the worse the anxiety gets and the more you think you may have done something wrong. After enough time, you start to believe that maybe you are not a friendly or good person! So, what do you do next? You send your friend a message saying you’re sorry—that you feel terrible for what you’ve done—even though you don’t know what that is! Then they write back and tell you they didn’t get back to you because their phone broke or they had an emergency. It wasn’t your fault at all.Your reaction in these situations reveals the effect of the “I” and the “me” having an internal conversation about who you are and how to present yourself. Such conversations may cause you to reflect on your identity. You can see the looking-glass self emerging. Your actions are based not on how your friend actually saw you but how you imagined they understood you. You may also see the social status of friend and its behavioural expectations (roles) emerge in the given scenario.

Presenting Myself

Imagine you’re in a classroom. You sit at a desk facing the front of the class with a pen or pencil in hand and a notebook. Perhaps you have your computer open. Someone enters the front of the room, dressed “professionally.” They place a bag on the front table, turn on a computer, and put PowerPoint slides on the screen. They say, “Welcome to class, today we’ll be talking about…” You think, this must be the teacher. You ask the instructor a few questions. The class ends. Your teacher goes back to their office. The teacher sees a colleague and says to them, “I wasn’t able to teach everything I wanted to in that class! I should’ve prepared less material!” Of course, you, the student, never know about that conversation the teacher has with a colleague.

In the scenario above, sociologist Erving Goffman (1959) would use his theory of dramaturgy to make sense of what was happening. He would tell us that individuals in society act much like actors do on stage. We perform convincingly to our various audiences—the student to their teacher, and the teacher to their students. In front of an audience, we behave with our roles in mind. This affects how we use our body to communicate, how we ask questions, how we lecture and lead discussion. The setting, the way we’re positioned, and the various props we use, such as computers, notebooks, and projectors, all help to make our front-stage performances believable to our public audiences. When we’re alone or with people whom we trust, we let our guard down and relax our bodies much like actors do when they go backstage. In these back-stage performances, we reveal things that were hidden or affected us emotionally in our front-stage performances.

It is tempting to think of front-stage behaviour as fake, and backstage as a place where a person can be his or her real self, but Goffman did not necessarily intend it this way. He would say they are both our real selves. In both settings, we imagine how other people perceive us and this affects our behaviour. However, with back-stage performances, we are less anxious about how we might be judged due to the trust and familiarity we have with those closer to us. In other words, the choices we make about how we present ourselves and fulfill our roles change in different contexts.

Socialization and Social Constructionism

Social constructionism says that we learn much of our identity from our families, communities, educational institutions, and other surroundings. We do not “come into the world pre-programmed with a sense of self and the knowledge necessary to act and interact appropriately with others” (Shaffir & Pawluch, 2014, p. 51). We learn this over time, often without even realizing it. We also learn how to present ourselves to manage other people’s impressions of who we are. And we come to understand different social statuses and the roles, or behavioural expectations, associated with them through interactions with others. In other words, social constructionism argues that our identities are formed through socialization. Socialization is “the lifelong process of social interaction through which individuals acquire a self-identity and the physical, mental, and social skills needed for survival in society” (Murray et al., 2014, p. 93).

This does not mean, however, that biological or psychological factors do not influence identity. We are born with certain qualities of character. Some children are naturally more expressive, aggressive, or sociable than others. However, it is through the social process of learning how to perceive and then express these qualities that our sense of self—our individual identity—is born.

Agents of Socialization

Those groups and institutions from which we learn how to identify and behave are known as agents of socialization, or socializing agents (Parsons, 1952). Examples of these include family, friend/peer groups, school, religion, and media.

Early in our lives, our primary agents of socialization are often our parents, guardians or family members (Berger & Luckmann, 1966, p. 131). From them we learn to imitate behaviour and how to act in relation to others. They also communicate values to us, through the things they tell us. How they act in relation to us teaches us about our own social status, child. These interactions also help us understand who and what our parents or guardians are—including their social statuses and roles.

A parent or guardian may feed, clothe and clean us. Through these acts, we understand that they are our protectors, and so we come to trust them…and test them! Because of this trust, parents or guardians can set boundaries for their children, for example, by telling their kids not to scratch their arms, pick their nose, or act out. This is socialization at work. Through this give-and-take relationship, we are engaged in a process of becoming. Children learn that they are children and how to be children by understanding things they are permitted to do, and not to do. Meanwhile, a parent or guardian also learns (or should learn!) about their social status and role as a parent or guardian by interacting with their children, as well as by learning from other parents and guardians about how to act and behave.

For another example of socialization, consider how people become religious or atheistic. A case could be made that we are born Muslim, Catholic, or atheist, but this is only part of the story. Now that we understand the social construction of identity and socialization, we know that we learn about our identity and social status, and the associated expected behavioural roles, from our environment. In other words, agents of socialization play a role in whether we become religious or not.

If you went to church every Sunday or mosque every Friday as a child, you would have learned certain traditions that determined how you act and behave in that environment. These would have reinforced your sense of being part of a religious community, and thus, your religious identity.

But your religious identity is determined by more than what happens in a religious space. It may be affected by the types of food you eat or don’t eat, such as not eating pork. You may participate in religious rituals, such as fasting during the holy month of Ramadan. Or you may have been told religious parables that shape how you act and think about the world. Events, foods, lessons, stories—all play a role in shaping your religious identity. And these don’t come from a single source like a religious institution. They come from school, family, friends. We learn about these things from agents of socialization, and they affect how our identities develop over time.

Socialization, Ideology and the Media

Another way we learn about social statuses and ways of being and acting is through media, such as advertisements, TV and radio, social media, and the internet. You’ll learn more about how this works in subsequent modules (you can jump ahead to them here and here). What is being transmitted to us through media is ideology, the topic of another module. In this section, we’ll begin making links between these concepts.

Media is a social institution. What we see in media is imbued with ideology, or beliefs or ideas about how society should work and be organized. In other words, media tells us how we should act and behave and what we should value (Festenstein & Kenny, 2010; Mullaly, 2007). When we see messages and ideas repeated over and over again in the media, they begin to shape our beliefs of who we can be and how we should behave. For example, if everywhere we look we see advertisements for products that we could potentially buy, we may start to believe in and see the world through the ideology of consumerism. Consumerism tells us that our happiness is tied to the things we buy, own and consume. This can shape our sense of self and even the social statuses we hold. For example, companies and organizations identify us by the social status of consumers or customers. We in turn may start to identify ourselves by these social statuses. This then will affect our actions and behaviour within particular social situations (Ahmed, 2016).

Have you ever watched an ad on TV or the internet and found yourself convinced that you must have the advertised product? If so, think through the following questions:

- Did the ad convince you that possessing the product will somehow make your life better or make you happier?

- What was the product? How was it presented to you?

- If you bought it, did it live up to expectations?

There are no right answers to these questions. But they do illustrate the ideology of consumerism and how it can convince us that buying or consuming something can improve our lives.

Historical Tendencies, Knowledge and Representations

In previous sections of this module, we have discussed how our identities are influenced by our interactions with others, our connections to groups and social institutions, such as family, religion and media, as well as our environment. Now we will consider how social statuses and roles developed and how they connect us to each other (as highlighted by the societal web).

Every society has particular ways of doing and knowing things. These develop over time. We can call them “historical tendencies.” These tendencies are revealed through the knowledge, ideas or representations that are repeated time and again in society and that people have come to generally accept as true (whether they are or not) (Grossberg, 1986, pp. 53-54). This knowledge can be found everywhere—books, TV shows, travel journals, scientific studies, reports, etc.—and is repeated to us such that we accept it as common sense. And it has a large effect on how people and places get represented.

These tendencies shape what we understand about different social statuses and expected roles because they impact and shape representations of people and places, as well as their social statuses and roles. They’ve also helped stereotypes flourish (which will be discussed in the next module more fully). The voiceover below provides an example of how historical tendencies can shape what we know of particular social statuses and how that can ultimately shape our behaviour.

Historical tendencies, in the end, make us realize that we are socialized to believe in our society’s way of doing and knowing things over time, but that doesn’t mean we can’t resist this. We can refuse to be socialized to accept certain ideas and behaviours. We can refuse to adopt the social statuses and the expected behaviours society tries to attach to us. However, we may encounter resistance if we try to identify differently or in new ways (Grossberg, 1986, p. 54).

What does the above discussion have to do with identities, anyway? Take a second and think of the social status of “professor.” When you think of a professor, who do you imagine? Do they wear glasses? A tweed sportscoat? (I wear tweed sportscoats!) Are they a man? White? Do they have a British accent? What a social status looks like in our heads serves as a reminder that this representation is the product of socialization. The fact that many of us imagine the same representation, despite being socialized differently, suggests that these ideas come from something a lot deeper than our simple connections with each other. Historically, people with certain identities—for example, white, male—have held the social status of professor. Even though this isn’t always true anymore, we may still associate the social status of professor with this representation. This is an example of how historical tendencies affect how we identify with or relate to and understand various social statuses and roles.

You might also think about why I, a professor, choose to wear tweed. Could it be that I have been socialized into thinking that’s what professors wear? Could I be doing it subconsciously so people will recognize me as a professor, since many people already believe professors wear tweed?

We could take this discussion in another direction still. Perhaps I just think that it makes good fashion sense and like it! Good point! But even if this is true, what helped create the conditions for me to like it? How did I even come to think about wearing tweed in the first place? Did it come from an idea about what “professor” as a social status entails? And what does this example say about how historical tendencies affect representation, social status, and how we relate to each other?

Finally, you might ask, what if a professor you’ve never met before came to class wearing a t-shirt and shorts? What would that make you feel about this professor and professors in general? Your answer to this question might reveal how historical tendencies affect social statuses and roles and perhaps how people may resist them.

Colonialism, Orientalism and Identity

One of the ways our knowledge and understanding of identities has been shaped is through a historical process known as colonialism. Colonialism can typically be understood as the political, economic or cultural domination of less powerful nations by more powerful countries (Dillon, 2010, pp. 400-401; Alexander, 2005, 181-182). Sometimes this domination can be seen when a powerful country takes over land and territory for its own interests. It can also be seen when a powerful country forces less powerful nations to exist and function using its own language, customs, practices and art, which it deems superior.

Powerful countries reasoned it was okay to dominate people of another country and take their resources by assigning those people a less valuable social status. In some cases, they continue this practice today. For example, First Peoples in Canada, like other Indigenous groups across the world, continue to be treated as inferior by the government. Their concerns are ignored, and their communities lack basic services. The government as well as non-Indigenous people and groups, meanwhile, make money off their land and resources, as well as their culture (Francis, 2012).

Colonialism’s legacy has affected our understanding of identities and difference, particularly in how it has played a role in defining social statuses of entire groups of people and the roles they are expected or imagined to play by those in relative positions in power. In the next module, you will learn about some of colonialism’s effects, for example, by thinking through stereotypes and discrimination.

Orientalism is a concept developed by Edward Said (2003) to explain how colonizing countries (mostly in Western Europe and North America) defined and identified people from other parts of the world. They described these groups of people as “other,” different, abnormal, exotic, backward, savage, inferior, etc. Doing this allowed them to position themselves as the opposite—as forward-thinking and superior. It was also another way to position these people as less valuable so that it was okay to dominate them.

These representations can still be found in society today. For example, Muslims have been portrayed negatively in Western countries. Today, we see this in media, where they are often connected to terrorism, torture, and war. They have also been represented as culturally abnormal or even “barbaric.” This affects how Muslims are seen and treated, by both non-Muslims and governments. In turn, this affects how Muslims understand their own sense of self and how they are able to participate in society.

Can you think of another example of a group of people being described and viewed as “other,” or backward or exotic? How has this affected the way they are treated?

Go Deeper

To learn more about Islamophobia in Canada, read this piece in The Conversation. (Source: Zine, 2019)

What happens when people catch on to false and misleading representations? Read this article about how a magazine cover hashtag prompted a social media response. (Source: Hotz, 2012)

Summary

In this module, we learned about the sociology of identity to help us understand how we came to be ourselves. Our identities are not simply chosen by us. Instead, they are affected by the people, environment, social institutions, history, and knowledge with which we come into contact. Recognizing how we are interconnected to other people sets us up to understand global citizenship and how we can act as global citizens by thinking of others and ourselves.

Key Concepts

Key Concepts

achieved status

A social status that is a result of an individual’s work, accomplishments, and/or abilities.

agents of socialization

Groups or institutions that play role in the process of developing our identities and the roles we play.

ascribed status

A social status assigned to an individual from birth. It is not chosen and cannot easily be changed.

audience

A group of people or a person to whom we perform our identities.

back-stage performance

The behaviour that we exhibit only when alone or around people we are close to and trust.

colonialism

The political, economic and cultural domination of one country over another group of people or nation. This can include taking land or resources.

discrimination

The unjust or unfair treatment of different categories of people, especially based on their race, age, or sex.

essentialism

A perspective that assumes that aspects of our identities are innate. We are born with them, and they remain fundamentally unchanged throughout our lives.

front-stage performance

The behaviour that we exhibit when in public or around less-familiar acquaintances.

gender-fluid

A gender identity that is not fixed to masculine or feminine.

hierarchy

A system of increasing value that ranks people based on certain criteria.

“I” and the “me”

Two key aspects of the self that allow a person to reflect on their actions and behaviours.

ideology

A defined set of beliefs and ideas shared by a group of people. Ideologies provide members of a group with an understanding and an explanation of their world.

Indigenous peoples

A catch-all term to describe the people who originally lived in an area. In Canada, this refers to First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples.

intersectionality

The experience, or potential experience, of multiple forms of discrimination based on the intersection of different social statuses.

looking-glass self

The theory that our ideas about our identity are formed through the way we imagine we are seen by others.

media

A social institution that involves channels of mass communication that reach a large audience.

media representations

The way people, events, places, ideas, and stories are presented by the media. These presentations may reflect underlying ideologies and values.

Orientalism

A term coined by Edward Said that refers how countries in the West define the people from the East without their input.

prejudice

A “preconceived opinion that is not based on reason or actual experience” (“Prejudice,” n.d.).

prestige

A form of social honour, or respect, that is valued by society or particular groups, and placed on people based on their social status.

props

Items, such as pencils, books, and computers, which play a role in our performances to other people. Props help people understand who you are and the social status you hold.

representation

A portrayal or re-presentation of something. In other words, a depiction or description meant to “stand in the place of” and “stand for” the original, but not the original itself (Hall, 1997, p. 16).

role

The social and behavioural expectations assigned to different social statuses, or positions in society.

setting

The physical environment and the location in which we act.

social constructionism

A perspective that argues that our identities are the product of society and culture, and are always changing.

social institutions

Established areas, organizations, or groups of organizations within a society that coordinate our actions and interactions with each other. Examples include: the economy, the political system, family, education, religion, mass media, and the law.

social status

The position or ranking a person has in relation to others within society.

social structure

The arrangement of social institutions into relatively stable patterns of social relations. The way a society is organized.

socialization

The process by which we come to understand different social statuses and their roles, or behavioural expectations, through interactions with others.

stereotype

“A widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person” or group (“Stereotype,” n.d.).

Global Citizenship Example

In the introduction to this module, I, Kritee Ahmed, did not simply identify myself as a man. I said I am brown, Bengali, Muslim, able-bodied, working class and a man, among many other things. We are not solely one social status at any one point. Many of them intersect at any given moment. Therefore, when we experience negative responses or positive successes for just being ourselves, it is important to note that this is not just because of a single social status we hold. It may be due to a combination.

Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) highlighted the multiple ways people experience the world with her idea of intersectionality. This concept underscores how thinking through identity in only one way limits our ability to understand the unique advantages and social disadvantages people can experience because of who they are. In the next module, you’ll learn more about this term. You will consider how the various social statuses you hold intersect. You will also think about why this may cause disadvantages, as well as prejudice or discrimination. Our identities are complex. We don’t experience them in the same way in different social situations.

So why is thinking about identity important to global citizenship, anyway? Well, for many reasons. Studying identity helps us understand the processes, such as socialization, that affect who we are and how we act. It lets us think about how our connections and interactions with other people shape us. In this light, it makes us socially and culturally aware. We can imagine how other people are shaped and affected by the connections and interactions in their lives and societies. In the coming chapters, we will use what we’ve learned to consider why certain groups are affected by social problems more than others. We will trace the roots of those social problems and work towards taking action to address them. Thinking through our own identities—how we became us and the forces that produced our identities—will enable us to make connections with others and act to create more justice in the world.

Could our social class—whether we identify as working class, middle class, or upper class—be considered a form of identity? How so? (More of this discussion can be found in the module discussing inequality).

Global Indigenous Example

The term Indigenous peoples is a catch-all term for people who are “[i]ndigenous to the lands they inhabit, in contrast to and in contention with the colonial societies and states that have spread out from Europe and other centres of [power]” (Alfred & Corntassel, 2005, p. 597). But it’s important to remember that Indigenous peoples do not have the same cultures. They also don’t have the same political, economic or social aims as other Indigenous groups or the societies that have been built around them (Smith, 2012, p. 6; Alfred & Corntassel, 2005, p. 597).

As a result, Indigenous groups use different language to identify themselves. This may happen for various reasons. Crucial to this is an understanding that not everyone is able to self-identify easily.

For some, identifying with a particular social status comes with a link to a particular culture, relationship and/or political situation. For example, in Ireland, as Joyce (2018) has noted, “Mincéirs (Irish Travellers) are a traditionally nomadic ethnic minority indigenous to Ireland, distinct from the majority Irish population.” The term “Traveller” was given to the community by outsiders because of their nomadic history. The name “Mincéirs” comes from their own indigenous language Cant/Gammon. They use this name to self-identify (Joyce, 2018).

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Indigenous people of the land are known as Maori. But Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012) writes that “Maori” also represents a colonial relationship between those who are indigenous to the land (Maori) and those who are non-indigenous settlers (Pakeha) (p. 6).

Alfred and Corntassel (2005) say the terms “aboriginal” in Canada and “Native American” in the US refer to those “who identify themselves solely by their political-legal relationship to the state rather than by any cultural or social ties to their Indigenous community, or culture or homeland (p. 599). In other words, these identities were established by colonial governments; however, Indigenous people may accept these terms as a means to attaining what they need to survive (pp. 598–599).

Go Deeper

To learn more about Irish Travellers, see Dr. Joyce’s article “Policing Travellers: Ireland’s Deeply Ingrained Racial Divide” here. (Source: Joyce, 2020)

Critically Thinking About Identity

Socialization is a useful concept to understand how people become who they are. It also explains how ideas get transmitted to us to shape who we think we should be. Keeping this in mind is useful when critically thinking about identity. It forces us to think about why our social status labels affect the ways we treat others with different social statuses. For example, you might want to consider whether you treat boys, girls, and gender-fluid children differently. Why would you treat kids of different genders differently? From where do our ideas about how to treat children of certain genders come? How have those ideas shaped your own identity?

We think through these things not to criticize our understanding of gender, but to consider the roots of these ideas and how they impact our actions and the actions of others. This can help us decide to act differently, perhaps in a more just way, keeping the global citizenship principles of equity and social justice in mind.

Using the key terms you’ve learned in this chapter, answer the following questions:

- What role does understanding your identity play in getting to know others?

- What are the expectations and assumptions attached to your social status? Do these expectations shift when your social status changes?

- Our identities are socially constructed. This means that we acquire them through our interactions with society. How is this true for your own identity? What social structures and institutions (school, media, parents, and friends) have shaped your identity, and how?

Sources

Licenses

Sociology of Identity in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action (2021) by Centennial College, Kritee Ahmed is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) unless otherwise stated.

Introduction photo by Hannah Xu on Unsplash.

References

This module contains material from “Understanding Identity,” by Selom Chapman-Nyaho & Alia Somani, in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action © 2015 by Centennial College.

Alexander, M. J. (2005). Pedagogies of crossing: Meditations on feminism, sexual politics, memory and the sacred. Duke.

Alfred, T., & Corntassel, J. (2005). Being Indigenous: Resurgences against contemporary colonialism. Government and Opposition, 40(4), 597–614.

Ahmed, K. (2016). Engaged customers, disciplined public workers and the quest for good customer service under neoliberalism. In M. Ivković, G. Pudar Draško, S. Prodanović (Eds.), Engaging Foucault (Vol. 2, pp. 46–62). Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory. http://instifdt.bg.ac.rs/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Engaging-Foucault-vol.2.pdf

Appelrouth, S., & Desfor Edles, L. (2007). Sociological theory in the contemporary era: Text and readings. Pine Forge Press.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

Craib, I. (1992). Modern social theory (2nd ed.). St. Martin’s Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. pp. 139–167.

Dillon, M. (2010). Introduction to sociological theory: Theorists, concepts, and their applicability to the twenty-first century. Wiley-Blackwell.

Elliott, A. (2014). Concepts of the self (3rd ed.). Polity Press.

Festenstein, M., & Kenny, M. (2010). Political ideologies. A reader and guide. Oxford University Press.

Francis, M. (2012). The imaginary Indian: Unpacking the romance of domination. In D. Brock, R. Raby, & M. P. Thomas, Power and everyday practices (pp. 299–320). Nelson Education.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

Grossberg, L. (1986). On postmodernism and articulation: An interview with Stuart Hall. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 10(2), 45–60.

Hall, S. (1990). Cultural identity and diaspora. In J. Rutherford (Ed.), Identity: Community, culture and difference (pp. 392–403). Lawrence and Wishart.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 13–74). Sage.

Hotz, A. (2012, September 17). Newsweek ‘Muslim rage’ cover invokes a rage of its own. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/us-news-blog/2012/sep/17/muslim-rage-newsweek-magazine-twitter

Joyce, S. (2018, November 29). A brief history of the institutionalisation of discrimination against Irish Travellers. Irish Council for Civil Liberties. https://www.iccl.ie/equality/whrdtakeover/

Joyce, S. (2020, January 8). Policing Travellers: Ireland’s deeply ingrained racial divide. European Roma Rights Centre. http://www.errc.org/news/policing-travellers-irelands-deeply-ingrained-racial-divide

Khanacademcymedicine. (2015, January 22). Charles Cooley- Looking glass self | Individuals and Society | MCAT | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bU0BQUa11ek

Mullaly, B. (2007). The new structural social work. Oxford University Press.

Murray, J. L., Linden, R., & Kendall, D. (2014). Sociology in our times (6th ed.). Nelson Education.

O’Brien, J. (2011). The production of reality: Essays and readings on social interaction (5th ed.). Pine Forge Press.

O’Brien, S., & Szeman, I. (2004). Popular culture: A user’s guide. Nelson.

Parsons, T. (1952). The social system. The Free Press.

Prejudice. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/prejudice

Said, E. (2003). Orientalism. Penguin.

Shaffir, W., & Pawluch, D. (2014). Socialization. In R. J. Brym (Ed.), New society (7th ed., pp. 50–72). Nelson Education.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Stereotype. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/stereotype

Stuart Hall – Obituary. (2014, February 11). Daily Telegraph. http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A358348176/STND?u=ko_acd_cec&sid=STND&xid=b54682a4

Zine, J. (2019, January 28). Islamophobia and hate crimes continue to rise in Canada. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/islamophobia-and-hate-crimes-continue-to-rise-in-canada-110635

Socialization: The Influence of Groups and Social Structure on Me

When Stuart Hall (1990) tells us that our identities are never an accomplished fact, he’s reminding us that identities can change over time and are affected by others around us. Sociologists like Mead and Cooley highlight how our interactions affect how we identify ourselves in relation to other people. Goffman builds on this to show how we understand our identities by reading the setting and context we’re in. These theorists highlight how our identities develop through limited choice—we understand our social status and roles based on perceptions of those around us.

But when we think about identities, we must move one step further and consider a concept called socialization. Socialization is the process through which we come to act and behave in line with an identity by learning about it from other people, groups, and social institutions (these are a part of society’s social structure). We have already discussed how our actions and behaviours are influenced by our interactions with other people and the environment we’re in. Now let’s think about how these actions and behaviours are influenced by our relationship to groups, institutions, and history.

Go Deeper

Connect the dots and think a little more deeply about how Cooley’s looking-glass self and socialization work together by watching this video. (Source: Khanacademymedicine, 2015)