Consider the impact of our increasing reliance on media: How does engaging with media shape our perceptions of each other, ourselves, and the world? Do you think media plays a role in informing your personal beliefs, opinions, and values? Why or why not?

Critical Media Literacy

Sabrina Malik

Our Use of Media

If you are like me, while you’re working or playing you usually have at least one screen open. Maybe your laptop is open to your course shell while you’re completing homework, and your television is playing a show on Netflix. Perhaps you are also chatting with your friends using your cellphone while streaming music online. More and more, we rely on media technology to connect with each other, gain information, entertain ourselves, and learn about the world beyond what we can experience directly.

As illustrated in the above scenario, the influence of media in our lives is undeniable. In today’s interconnected world, where we find ourselves living in a global village, our ability to critique and analyze media messages is increasingly important. In this module, we will examine how we define media, the importance of critical media literacy, and media as a social structure. We will also explore media bias, regulation, and consolidation. Finally, we will consider how advertising and news coverage influences our understanding of social and global issues.

What Is Media?

Media is a social institution that involves channels of mass communication that reach a large audience. For example, some types of media are television, film, and radio; traditional print media such as books, magazines, and newspapers; and digital media such as the internet and social media. We use media for many reasons: to stay informed, to be entertained, to express our thoughts, feelings, and opinions, and to keep us connected to others in our social network.

We are constantly surrounded by media messages. Think about the last time you commuted to school or work. Chances are you read several advertisements posted in the subway and on billboards. Perhaps you checked social media sites or watched your favourite television show on your mobile device. Maybe you picked up a newspaper to get caught up on local and world events. Media messages can be found everywhere. It is difficult to escape the impact these messages have on how we view ourselves and others.

Go Deeper

This short introduction explores what media is and how we define media. The video asks its viewers to consider the types of media they engage with daily. (Source: MediaSmarts, 2013)

This video explains what media is and why media analysis is important in the current digital era. An introduction to the necessity of critical media literacy is also provided. (Source: McPherson, 2018)

Are you using media, or is media using you? Have you noticed that when you click on a link, or if you like a post on social media, that you will suddenly start seeing ads that reflect what you clicked on or liked? Did you know that your cell phone service provider can track your movements and sell that information to marketing research companies? This is the new reality of “big data.” As we will learn later in this module, big data is not just about gathering information, it’s about profiling citizens for profit. Most of us are giving away our personal data without fully understanding that we’re doing it.

To learn more about big data and its implications, watch the video from The Guardian called “Big Data: Why Should You Care?” It can be found in the Go Deeper section under the Regulating the Internet and Big Data sub-topic

The Importance of Media Literacy

Media is so common in our everyday lives that we may take it for granted. We might assume, for example, that the news stories we read are reliable sources of information. We might see advertisements as forms of media that affect other people, but not us. We might think of social media as simply a way to share information and connect with friends. But, as we will see throughout the module, media does not exist outside the realm of power, ideology, and social structures.

Critical media literacy is an approach to thinking about media messages and learning to read media text. “Text,” in this case, refers not just to words but also to images, sounds, and video. When you read media text, you consider all elements and how they contribute to the overall message. To “read” media text means to analyze its direct and indirect messages critically and actively. As you read, you will question what specifically is being communicated.

Go Deeper

John Randolph (better known as Jay Smooth) is a cultural commentator, founder of New York City WBAI radio station’s hip hop program Underground Railroad, and creator of the video blog Ill Doctrine. In this video, he explains what media literacy is. He also discusses how to use media literacy as a tool to navigate the many messages we receive through the mass media. (Source: CrashCourse, 2018a)

Andrea Quijada is a media literacy educator and executive director for the Media Literacy Project. In this video, she speaks about her experiences teaching others how to “deconstruct” or analyze media messages. She asks us to consider the text and “subtext” (the hidden meaning) of media messages and encourages us to question what we see and don’t see in the media. (Source: Quijada, 2013)

Media as a Social Structure

Media acts as a powerful agent of socialization. We learn about ourselves and others through the media representations we find in popular media, whether on television, in films, in advertisements, or online. These messages may not affect us immediately. Instead, as we are continually exposed to them, they become part of our worldview over time.

For example, consider how media and advertising represent gender roles. Girls’ toys, such as baby dolls and toy kitchen appliances, are often based in the domestic realm. For boys, toys often mirror the world outside of the home, such as toy cars and trucks. As we age, we are continually exposed to gendered representations in the media that reflect these norms and expectations: that women belong at home, and men in the labour force.

The media appears to mirror reality back to us. But this is an illusion. In fact, it gives us a very limited and often false representation of our world. For example, media often encourages us to adopt dominant ideologies and norms, ones that may create and maintain social inequalities. It takes time to reflect and critically analyze all the media messages we see and hear. We may see the same headline repeated in the news so often that we take the message as fact. In our busy lives, we often rely on limited descriptions of issues in the media to form our judgments and create our opinions.

Much of our view of reality is based on media messages, so it is important to consider who created the message and why. What is the purpose of the message? What is being communicated in the message, and what is being left out? By critically examining media messages, we have the power to pick and choose which messages are truer to us or more representative of our lived reality than others.

Go Deeper

Educator, author, and social theorist Jackson Katz explores issues related to violent masculinity in popular media. This documentary examines representations of gender and race in popular films, television shows, and news stories. It discusses the impact of these harmful messages on culture and society. (Source: Katz et al., 2013)

Media Bias

Media bias generally refers to the particular slant or perspective of media messages that influences how specific issues or people are presented. For example, media representations often reflect bias. Media bias also refers to how media tends to represent and spread dominant ideologies. This can lead to prejudiced attitudes and opinions, as well as stereotyping and discrimination, most often of minoritized and marginalized groups.

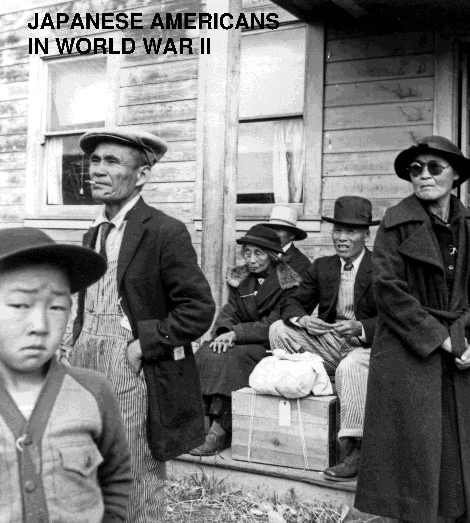

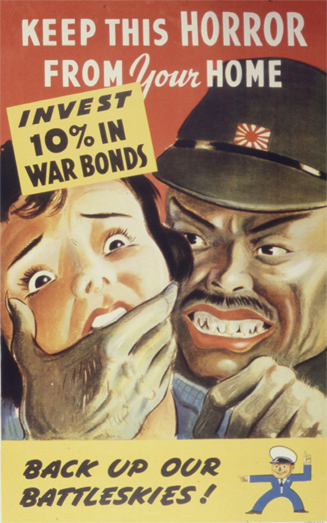

The images and language used to describe an event or issue can reflect and contribute to the bias of a media message. For example, as we will see in the video found in the Go Deeper section below, an advertisement from the 1940s describes the camps where Japanese residents of Canada and the United States were imprisoned during the Second World War as “assembly centres.” In fact, these were temporary concentration camps for people of Japanese ancestry. Those forced to live and work at these camps spent an average of three months there before being transferred to a permanent concentration camp (Linke, 2015).

“Japanese Americans in World War II, a National Historic Landmark theme study” by Dorothea Lange, United States National Park Service (Public Domain).

” (Public Domain).

Biased news reporting influences how the public feels about issues. One way bias in the news can occur is through a process of selection and omission, where an editor may choose to include only some details of a story, while ignoring others. Another way bias can creep in is through the use of negative language. One survey of newspaper articles about unions found that negative terms such as “demands,” “inconvenience,” “labour unrest,” and “greedy” kept occurring (Finn, 1983, as quoted in Naiman, 2008). How might this affect how readers feel about unions?

How an event is described and what choice of words are used feed into dominant discourses. These discourses recreate and maintain inequities. The way the world is represented in the media will always contain bias. So it is important to learn how to recognize limiting perspectives and to seek a variety of sources and points of view.

Identifying bias in a news headline

Consider the following headlines:

More than 900 people attended the protest!

vs.

Less than a thousand people attended the protest.

Are these headlines describing the same or different events? What is the perspective of each? How does the choice of words used in the headlines contribute to bias?

Go Deeper

This video explores ways in which we can learn how to recognize bias in the media. What words are chosen to describe people and events can lead to biased reporting in the news, as well as issues surrounding false information disguised as fact – or “fake news.” (Source: PBS NewsHour, 2017)

Other Sources

Media literacy: Five core concepts. (n.d.). Young African Leaders Initiative. https://yali.state.gov/media-literacy-five-core-concepts/

Savvy info consumers: Detecting bias in the news. (n.d.). University Libraries, University of Washington. https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/evaluate/bias

Serani, D. (2011, June 7). If it bleeds, it leads: Understanding fear-based media. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/two-takes-depression/201106/if-it-bleeds-it-leads-understanding-fear-based-media

We learned how bias is created in the media and specifically in news reporting in this module. Biased news reporting can occur in three ways: through selection and omission, placement, and headlines. As you now know, selection and omission refers to which aspects of the story are included and which are left out. This type of bias can be the outcome of space considerations or advertising pressure on editorial decisions. Because of this type of bias, it is important to consider different sources of news to get a fuller picture of events. Bias can also occur through placement—where does the story appear? Is it on the front page of a newspaper or magazine, or is it the first story covered in the news on television? Does it appear on the front page of the news website? Or is it buried somewhere and given a very small word count? Placement of news stories determines how relevant the story is to media producers, and ultimately to us as media consumers. It sends a subtle message to us about what is important and what isn’t. Finally, bias can occur through the news headline. Headlines usually contain very few words, and these words are chosen carefully. In journalism, there’s a saying that “if it bleeds, it leads”: the more shocking or provocative the headline, the more likely it is to grab the reader’s attention. You can read more about the creation of fear-based media in the article called “If It Bleeds, It Leads: Understanding Fear-Based Media” in the Go Deeper section of the Media Bias sub-topic.

Representation in the Media

Growing up as a child of immigrants to Canada, it was rare to see people like me fairly represented in the media. I didn’t see many South Asian people on TV or in the films I watched. The representations that I did see were stereotypical, negative, and simplified. They made me feel ashamed of who I was. Over time, I began to question the validity of my experiences. Today, I see more diversity in popular media, but I still question how accurate and representative these depictions really are.

Do you see yourself fairly represented in the media? Are your experiences and lifestyle reflected in the films you watch or the news stories you read? Why might this be important to consider?

Representation in the media often reproduces stereotypes about gender, race, class, ethnicity, religion, ability, and sexuality. This is because media recreates inequalities that exist in our society. When examining how diversity is represented in the media, it is important to consider three main issues: inclusion, roles, and control of production (Croteau & Hoynes, 2003). For example, we may ask if media includes diverse perspectives of racialized groups in Canada. We may question how racialized groups are portrayed in the media by exploring the roles their members are given. Finally, we may consider who is controlling the creation and production of media.

Representation and Race

As we saw in the previous module on media bias, what the media chooses to reflect is very selective. Overt or obvious racism is less present in media representations today. However, subtle racism is still very much present (Hall, 1995). This often shows up in representations that feel natural but in fact hold unquestioned assumptions about race.

An example of this is how Africa is continually portrayed as a region marked by corruption, famine, and civil war. Those issues have been present in Africa. However, there are many other positive stories about Africa that are never mentioned. These include successful community development projects and the rapid growth of the movie industry in Nigeria.

This sort of subtle racism also occurs closer to home. Usually in stories about First Peoples in Canada, the focus is on corruption on reserves, violence, and alcoholism. Rarely do we hear positive stories about Indigenous art, culture, or leadership.

Media representations of Indigenous groups recreate harmful stereotypes. Stuart Hall (1995) describes this representation in popular media as having two sides. On one side is the stereotype of Indigenous groups as “noble and “primitive.” On the other side is the stereotype of Indigenous groups as “savage” and “uncivilized” (p. 21). These representations have fed into the marginalization of Indigenous communities.

In these examples, we can see how the media reflects and contributes to the racism present in our society.

Representation and Gender

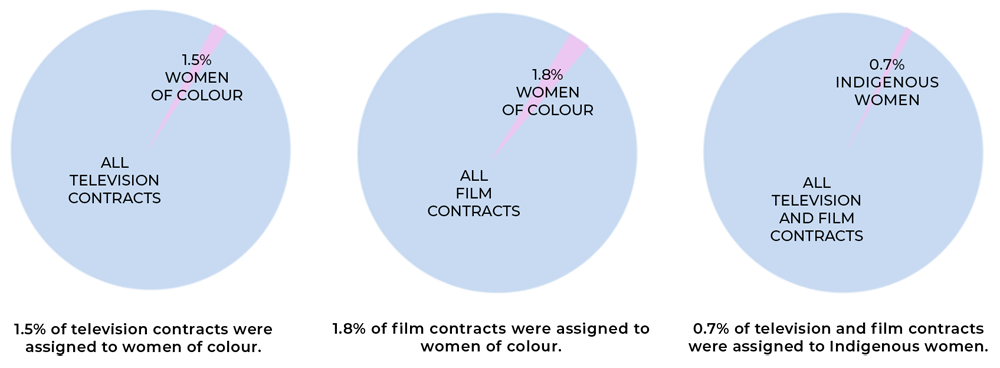

Although gender balance has improved in film and television in recent years, women of colour and Indigenous women in Canada are still extremely underrepresented in the media, both in front of and behind the camera. A recent study by the not-for-profit organization Women in View analyzed 90 television shows publicly funded by the Canadian Media Fund (CMF) airing between 2014 to 2017, and 1098 film productions funded by Telefilm between 2015 and 2017. They found that only 1.5% of television contracts and 1.8% of film contracts were assigned to women of colour. Alarmingly, only 0.7% of television and film contracts were assigned to Indigenous women. In 2017, of 24 television shows created, not one had any Indigenous women on staff (Collie, 2019).

Today, stereotypical representations in the media can be more subtle than they have been historically. Think of a television show or movie that you have watched recently and consider applying the Bechdel test. This test asks if there were at least two women in the film who talk to each other about something other than a male character. This is how it assesses if female characters are present and how complete or well-rounded they are. This simple test can help determine if there is equality of gender representation.

Representation and Class

Media representations of people experiencing poverty tend to frame their struggles as an individual problem, and not as a social problem. By doing so, they encourage us to believe that we can avoid such struggles through personal effort, such as hard work. Those who are struggling are often described as not working hard enough or exploiting social supports. In other words, they are blamed for their own poverty. For example, people who claim government benefits may be described in the media as “undeserving” of benefits or as committing fraud (Thompson, 2019).

Often we see media representations of wealthy lifestyles. These do not reflect the reality of most citizens. The vast majority of American and Canadian citizens work in service, manufacturing, or production jobs (Croteau & Hoynes, 2003, p. 218; Statistics Canada, 2020). These images are most obvious in advertising. For example, ads do not typically feature working class people. They portray images of white, middle class, and affluent upper-class people (p. 218). These messages make us feel anxious about our current lifestyle. They are also usually offering ways to fake our social status by purchasing luxury products and brand names. Consider the following question: How do these messages from advertising campaigns feed into the ideology of consumerism?

Reflect on the impact the media has on how you view yourself and others. How does the media feed into existing power structures? What does the media tell us about ourselves and those around us? What values, lifestyles, or points of view do you see represented or omitted in the media?

Go Deeper

In this TED talk, researcher Min Kim explores how our understanding of others is filtered through media images and the perspectives chosen by the owners of mass media. He argues the benefits of direct experience over filtered experiences. (Source: TEDx Talks, 2017b)

Cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s theory of representation is explored in this video, with attention on his groundbreaking work on the relationship between stereotypes, power, and the media. (Source: The Media Insider, 2019)

Artist, photographer, and educator Bayete Ross Smith examines how media images of people of colour shape our perceptions and create stereotypes in this TEDx Talk. He explores how art and media can be used as tools to educate and expose the many stereotypical representations we see during our lifetimes. (Source: TEDx Talks, 2015)

Other Sources

Bechdel Test Movie List. (n.d.). https://bechdeltest.com/

Lawson, K. (2018, February 20). Why seeing yourself represented on screen is so important. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/zmwq3x/why-diversity-on-screen-is-important-black-panther

Statistics Canada. (2020, June 5). Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-20-0001/142000012018001-eng.htm

Women in View. (2019, May). Women in View: Onscreen Report. [Report] Women in View. http://womeninview.ca/reports/

Media Ownership

In Canada and the US, most of the newspapers, radio stations, television stations, and internet providers are owned by a few very large corporations. This is referred to as media consolidation.

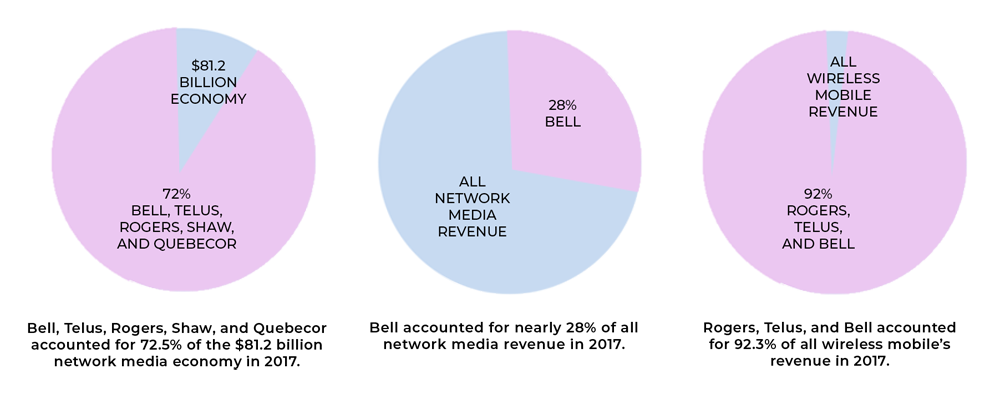

The top five media companies in Canada are Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw, and Quebecor. These five corporations accounted for 72.5% of the $81.2 billion network media economy in 2017. Bell, the largest media company in Canada, accounted for nearly 28% of all revenue in 2017, up by one percent from the previous year. Wireless mobile is also extremely concentrated. Rogers, Telus, and Bell accounted for 92.3% of the sector’s revenue in 2017 (Winseck, 2018).

From a critical media literacy perspective, we must ask what issues arise when a few very large companies own so many media outlets. For example, are these companies constructing media messages to gain and maintain power? Do they create and spread ideas that help them maximize their profits?

With this level of consolidation, it is important to question in whose interest media messages are created, and why.

Go Deeper

Read the Media and Internet Concentration in Canada Report 1984–2017. (Source: Winseck, 2018)

Learn more about the major companies in the media landscape here. (Source: Molla & Kafka, 2018; this source is kept updated)

This video provides an overview of media concentration in the US. (Source: NowThisWorld, 2016)

The history of media ownership and concentration is explored in the eighth installment of Jay Smooth’s Crash Course in Media Literacy. Issues surrounding mergers and monopolies by media corporations are examined, including tech companies and access to the internet. (Source: CrashCourse, 2018b)

Media Regulation

The government of Canada plays an important role in media regulation. In other words, it determines what media and media content we have access to.

In Canada, the government body that controls media is called the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The CRTC was created in 1968 by the Broadcasting Act. It oversees all sectors of the Canadian broadcasting system, including radio and television. Before the CRTC was created, this responsibility belonged to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). The CBC was created in 1936 to provide an alternative to American radio.

The CRTC plays many roles. Companies that wish to operate radio and television broadcasting networks must first apply for a license from the CRTC. In addition, companies that want to buy or take over other broadcasting companies must receive approval from the CRTC.

The main role of the CRTC is to ensure Canadian culture is represented in media. However, large media corporations have pressured the government to change their policies so that they do not need to represent Canadian culture in their programs. This has made it very difficult for the CRTC to fulfill this role (McChesney, 2008). In addition, the increasing concentration of media ownership in Canada has not been challenged by the CRTC.

Media can be controlled and owned in various ways. For example, private-sector control of the media includes media that is produced and distributed by corporations for a profit. In contrast, media controlled by the public sector refers to media that is produced and distributed as a public service, and not necessarily to generate any profit. Here are some examples of different ways that media can be controlled.

Media produced by media corporations and media conglomerates to make a profit.

Media supported, regulated, and controlled by the government. State-controlled media acts as a tool for social control. The only information citizens have access to must be approved by the state and is most often in support of the government. In countries with state-controlled media, independent media sources may be suppressed or banned. This can threaten journalistic integrity and promote the state’s interests over its citizens.

Media produced by public film and broadcasting organizations. It provides a public service by creating content that does not necessarily produce a profit. In other words, it serves public instead of corporate interests, e.g. TVOntario.

Media in which people directly participate. This includes citizen journalism, blogs, social media sites like Twitter and Facebook, opinion pieces, etc. It is also called participatory media.

Go Deeper

Learn about the statutes and regulations of the CRTC here. (Source: Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, 2019)

In this report, the Committee to Protect Journalists describes 10 countries where independent media is suppressed or banned. (Source: Wang, n.d.)

Regulating the Internet and Big Data

What do you do online in a typical day? Check your social media pages to get updates from friends? Read reviews on the latest cell phones? Post a picture on Instagram? Find a map for directions to a restaurant? Everything you do online is tracked. The online trail you leave of your interests, movements, and purchases is your personal data, and it’s extremely valuable. If you’ve ever noticed advertisements “pop” up that seem to offer the kinds of products and services you’ve been recently browsing, then you’ve had a glimpse at why companies are willing to pay for your data. They harness it to target sales to you. Here’s how it works.

The term “ big data” is important to understand because your free internet is built on it. You likely pay for an internet connection, but once you are online, you don’t pay for the actual internet—the online world where all your websites live. That is because there is an important difference between data and “big data.” Data is simply information. Even if you have a lot of information, it may not be very useful. For example, if you tracked how many people purchased shoes online in Canada, you would have data. However, this data would not help you sell more shoes online. Big data takes online shoe purchase numbers and then combines them with other information about those shoe buyers, such as their age, income, etc. This combination of data produces very valuable information for advertisers. With big data, shoe companies know which shoes to advertise to which people. It also tells companies where to place those ads, when to place those ads, and what prices to offer the shoes in those ads. Big data is not about the shoe. It’s about you. (Source: Anderton, Centennial College, 2020)

Regulating the internet is an issue of concern for most Canadians. The majority of Canadians (60%) believe that the government should step in to address disinformation and data privacy issues created by social media platforms (Wong, 2019). These issues have been highlighted by Brexit, the Trump presidency, and the Cambridge Analytica scandal (covered in more detail in Media 2). A general distrust is developing towards social media companies, in particular Facebook. People are becoming increasingly uncomfortable with how big tech companies target them for political and sales advertising. This, along with the fact that the internet is now controlled by a few large companies, has challenged the idea of net neutrality as well as democracy more generally.

Go Deeper

This video on big data by The Guardian explains how data is gathered on individuals. It also explains what companies can do with this information, such as target advertisements and political campaigns, or predict your future actions. (Source: The Guardian, 2019)

In this video, senior reporter and policy editor Russell Brandom explains how the end of net neutrality has given big companies the power to control internet access and streaming services. (Source: The Verge, 2018)

After watching the videos on big data and net neutrality, do you think our role as global citizens is being challenged by big tech companies? Why or why not?

Other Sources

Finley, K. (2020, May 5). Net neutrality: Here’s everything you need to know. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/guide-net-neutrality/

Lytvynenko, J., Boutilier, A., Silverman, C., & Chown Oved, M. (2019, April 9). The Canadian government is considering regulating Facebook and other social media giants. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeed.com/janelytvynenko/canada-social-media-regulation

Malik, N. (2018, September 7). The internet: To regulate or not to regulate? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nikitamalik/2018/09/07/the-internet-to-regulate-or-not-to-regulate/#4985a0141d16

Media and Advertising

Advertising is the primary way media companies make money. Because of this, advertisers have great control over the content of media, as well as the owners of media companies. As explained in Robert McChesney’s Rich Media, Poor Democracy, media conglomerates now own many different types of companies. These may include publishing companies, promotion companies, production companies, television and radio stations, and newspapers. This is called vertical integration. It allows media conglomerates to maximize profits by a process called “ synergy,” which involves the following:

This refers to how conglomerates turn movies into books; books into movies; movie music into soundtracks; hit movies into TV shows, etc. Because media conglomerates own companies that create different types of media content, they can take one product and find many ways to profit from it.

This refers to when a corporation promotes their entertainment product (movie, book, etc.) within their own media outlets. For example, a movie production company may promote their movie on a television “entertainment” show or news program owned by the same company. Deals may be made with food companies and restaurant chains to have the characters appear on cereal boxes, “kids’ meals,” toys, bed sheets, video games, etc. Some of these companies might also be part of the same media conglomerate. This means the profits stay with the same company, another example of vertical integration. Disney is a good example of a powerful media company that uses cross-promotion for their products and branding.

Movie productions can cost hundreds of millions of dollars. This makes them very risky and expensive. That risk is reduced if the production company is owned by a media conglomerate. The conglomerate has the ability to aggressively promote the film. It can make sure it gets good reviews in the newspapers, magazines, and television media it owns. It can advertise and promote it widely. Therefore, big media corporations can help reduce risk and guarantee their products make money.

In the 1990s in both the US and Canada, governments removed some regulations on media companies. This allowed them to merge different media sectors together to create media conglomerates. As new technologies emerged, these too were taken over by media conglomerates. This deregulation was supposed to promote competition. However, it caused media companies to overpower and buy competing companies. So, in fact, it reduced competition. The 1996 Telecommunications Act made it possible for corporations to own large segments of the media sector. As a result, deregulation benefited these businesses more than the public.

Go Deeper

Media theorist Robert McChesney and media scholar Mark Crispin Miller demonstrate how conglomerates influence media content in this film. They show how power in the hands of a few produces a system of media that feeds into consumerism and biased news reporting. (Source: Smith et al., 2003)

Manufacturing Consent: The Five Filters

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman are American media analysts and educators. They argue that corporate media uses five “filters” to determine what is considered “newsworthy.” These filters are: corporate ownership, advertising, sourcing, negative responses to a media statement or program (“flak”), and creating polar opposites.

Due to media consolidation, a small number of large corporations control the media. Major media corporations are very large companies seeking to make money, and they directly influence editorial content. Chomsky and Herman remind us that very wealthy and politically connected people sit on the boards of these corporations.

Advertising is essential to the success of any newspaper or television station. It is how they make money. Because media outlets want to attract and keep their advertisers, they are often biased towards their business interests. Chomsky and Herman point out that corporations that buy major advertising space can influence what content is printed or broadcast. These large companies have the power to withdraw their advertising dollars if they disagree with editorial content.

Sourcing is where media outlets get their news information. For example, the media gets information about important issues involving the government from government sources. This means that this information is highly controlled and regulated. Governments also control media through the laws they create. These laws might protect public interest or promote competition among media outlets. Those who control and regulate the media can influence what stories and information are presented in the news.

“Flak” refers to negative responses to a media statement or program. It may take the form of letters, phone calls, petitions, lawsuits, speeches, and legislation. It includes any type of complaint, threat, and punishment. These responses may be highly organized by a group or independent actions of individuals. For example, governments and advertisers can control media content by providing inaccurate, misleading, or biased information. They can threaten to pull their business (ads). In the case of the government, it can cut off their sources of information if they don’t cooperate. They can also threaten media companies with lawsuits (libel) and forced public apologies.

This filter refers to the ability of the media to create a perceived enemy or “other.” Major media outlets may create a story of “us” versus “them,” or “good” versus “evil.” This influences the public to pick a side. Usually, the public is encouraged to side with the position of the government or corporations and support their goals. These goals might be to buy more products (consumerism) or to support a political agenda. For example, in Canada the oil industry in Alberta is often portrayed in the media as benefiting the country’s economic interests. The Green Party of Canada (concerned with the environmental issues related to big oil) is shown as not representing national interests.

Go Deeper

In this video, the five filters of media are explored in relation to the propaganda model from Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’s writing in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988).

Summary

In this module, we examined how media is defined, the importance of critical media literacy, media as a social structure, media bias, regulation and consolidation, and the influence of advertising and news coverage on our understanding of social and global issues.

Key Concepts

Key Concepts

Bechdel test

A simple test to determine the representation and inclusion of well-rounded female characters in films and TV.

big data

“Extremely large data sets that may be analysed computationally [by computers] to reveal patterns, trends, and associations, especially relating to human behaviour and interactions” (“Big data,” n.d.).

consumerism

An ideology that connects our happiness to the things we buy, own, and consume.

critical media literacy

The ability to analyze and evaluate how media messages influence our beliefs and behaviours. In this process, viewers are not just recipients of media messages. They actively critique media content.

discrimination

The unjust or unfair treatment of different categories of people, especially based on their race, age, or sex.

disinformation

“Information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organisation or country” (UNESCO, 2021).

dominant discourses

How the common-sense ideas, assumptions and values of dominant ideologies are communicated to us. Dominant discourses can be found in propaganda, cultural messages, and mass media.

dominant ideologies

Ideologies that are particularly influential in shaping our ideas, values, and beliefs because they are supported by powerful groups.

First Peoples

Peoples indigenous to Canada; includes First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

global village

The idea that the entire world is becoming more interconnected because of advances in technology. This makes it possible to deal with the world as if all areas of it were local.

media

A social institution that involves channels of mass communication that reach a large audience.

media bias

The act of favouring one perspective over others by the creators of media messages.

media conglomerate

A media company that owns many other media companies.

media consolidation

The process by which the ownership of media is concentrated into the hands of a small number of large corporations.

media messages

The main idea or moral of the story that is communicated by the content and type of media, such as in a television show, an advertisement, a news article, a song, etc.

media regulation

Government control of mass media through laws that may protect the public interest or promote competition among media outlets.

media representations

The way people, events, places, ideas, and stories are presented by the media. These presentations may reflect underlying ideologies and values.

media text

Refers not just to words but also images, sounds, video, taken as a whole message.

minoritized

Experiencing discrimination and other disadvantages compared to members of the dominant group.

net neutrality

“The concept that all data on the internet should be treated equally by corporations, such as internet service providers [ISPs], and governments, regardless of content, user, platform, application or device” (Kenton, 2020).

norms

Social expectations about attitudes, values, and beliefs.

prejudice

A “preconceived opinion that is not based on reason or actual experience” (“Prejudice,” n.d.).

racialized

The process of creating, preserving, and communicating a system of dominance based on race.

selection and omission

A process through which bias is expressed in the news, where editors may choose to share only some details of a story, while ignoring others.

socialization

The process by which we come to understand different social statuses and their roles, or behavioural expectations, through interactions with others.

stereotype

“A widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person” or group (“Stereotype,” n.d.).

synergy

When two or more media companies work together to produce and control one brand.

vertical integration

The control of two or more stages of media production by one media company.

Global Indigenous Example

The Indigenous Media and Communication Caucus at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) was founded in 2016. It was created by Indigenous journalists and media practitioners from Bolivia, Guatemala, Nepal, and Venezuela. The aim of the caucus is to increase Indigenous voices and participation in media, as well as access to media. It also seeks to strengthen the use of Indigenous languages in the media within state and international legal frameworks.

Read this article to learn more about the caucus. (Source: Sunuwar, 2019)

You can visit the caucus website here. (Source: Indigenous Media Caucus, n.d.)

Global Citizenship Example

In this module, we learned how big data has created issues with disinformation and privacy rights. However, it can also be used to identify social problems and solutions. For example, access to clean cooking fuel is a huge problem in India. The traditional cooking method can expose a person to toxins equivalent to smoking 400 cigarettes. The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas partnered with SocialCops to bring clean cooking fuel to 80 million women below the poverty line in just four years. To do this, they used big data to identity the need for liquefied petroleum centres (LPGs) in rural communities in India.

To learn more, watch this TedX video. (Source: TedX Talks, 2017a)

You can also visit the SocialCops website here. (Source: “Data to decisions,” n.d.)

Other Sources

Learn more about how big data is used for the greater good.

Lebied, M. (2019, December 10). 12 examples of big data in healthcare that can save people. Datapine. https://www.datapine.com/blog/big-data-examples-in-healthcare/

Panah, A. S., & Mccosker, A. (2018, November 2). Five projects that are harnessing big data for good. Government Technology. https://www.govtech.com/analytics/Five-projects-that-are-harnessing-big-data-for-good.html

Sources

Licenses

Critical Media Literacy in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action (2021) by Centennial College, Sabrina Malik is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) unless otherwise stated.

Introduction photo by camilo jimenez on Unsplash.

References

This module contains material from the chapter “Media Literacy” by Sabrina Malik & Jared Purdy, in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action © 2015 by Centennial College, and material adapted from class materials for GNED500 Global Citizenship by P. Anderton, Centennial College.

Al Jazeera English. (2017, March 2). Noam Chomsky: The five filters of the mass media machine [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/34LGPIXvU5M

Bechdel Test Movie List. (n.d.). https://bechdeltest.com/

Big data. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/big_data

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. (2019, October 3). Statutes and regulations. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/statutes-lois.htm

Collie, M. (2019, May 28). The lack of diversity in Canadian media is ‘hard to ignore’ – and the numbers prove it. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/5297230/women-of-colour-indigenous-canadian-media-diversity-women-in-view/

CrashCourse. (2018a, February 27). Introduction to Media Literacy: Crash Course Media Literacy #1 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AD7N-1Mj-DU

CrashCourse. (2018b, April 17). Media ownership: Crash Course Media Literacy #8 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvSTlxJsKzE

Croteau, D., & Hoynes, W. (2003). Media/society: Industries, images, and audiences (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Data to decisions. (n.d.). SocialCops. https://socialcops.com/

Finley, K. (2020, May 5). Net neutrality: Here’s everything you need to know. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/guide-net-neutrality/

Hall, S. (1995). The whites of their eyes: Racist ideologies and the media. In G. Dines & J. M. Humez (Eds.), Gender, race, and class in media (pp. 18–22). Sage Publications, Inc.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. New York: Pantheon Publishers.

Indigenous Media Caucus. (n.d.). https://www.indigenousmediacaucus.org/

Katz, J., Young, J., Earp, J., & Jhally, S. (Directors). (2013). Tough Guise 2 [Video]. Media Education Foundation. https://centennialcollege.kanopy.com/video/tough-guise-2

Kenton, W. (2020, January 29). Net neutrality. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/net-neutrality.asp

Lawson, K. (2018, February 20). Why seeing yourself represented on screen is so important. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/zmwq3x/why-diversity-on-screen-is-important-black-panther

Linke, K. (2015, July 31). Assembly centers. In Densho Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Assembly%20centers/

Lytvynenko, J., Boutilier, A., Silverman, C., & Chown Oved, M. (2019, April 9). The Canadian government is considering regulating Facebook and other social media giants. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeed.com/janelytvynenko/canada-social-media-regulation

Malik, N. (2018, September 7). The internet: To regulate or not to regulate? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nikitamalik/2018/09/07/the-internet-to-regulate-or-not-to-regulate/#4985a0141d16

Marshall McLuhan’s theory of the global village. (1960, May 18). CBC Archives. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/marshall-mcluhan-the-global-village

McChesney, R. W. (2008). The political economy of media: Enduring issues, emerging dilemmas. New York: Monthly Review Press.

McPherson, K. [GNED500 Global Citizenship, Centennial College]. (2018, August 15). Week 5: What is media? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LIgQoBRPpSs

Media literacy: Five core concepts. (n.d.). Young African Leaders Initiative. https://yali.state.gov/media-literacy-five-core-concepts/

MediaSmarts. (2013, October 17). Media Minute Introduction: What is media anyways? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBP_kswrtrw

Molla, R., & Kafka, P. (2018, January 23). Here’s who owns everything in Big Media today. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/1/23/16905844/media-landscape-verizon-amazon-comcast-disney-fox-relationships-chart

Naiman, J. (2008). How societies work: Class, power, and change in a Canadian context (4th ed.). Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

NowThisWorld. (2016, March 21). Who owns the media? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awRRPPE3V5Q&feature=emb_logo

PBS NewsHour. (2017, June 6). How media literacy can help students discern fake news [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/z4fwJHhv6ZY

Prejudice. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/prejudice

Quijada, A. [TEDx Talks]. (2013, February 19). Creating critical thinkers through media literacy: Andrea Quijada at TEDxABQED [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHAApvHZ6XE&t=17s

Savvy info consumers: Detecting bias in the news. (n.d.). University Libraries, University of Washington. https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/evaluate/bias

Serani, D. (2011, June 7). If it bleeds, it leads: Understanding fear-based media. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/two-takes-depression/201106/if-it-bleeds-it-leads-understanding-fear-based-media

Smith, J., Alper, L., Robb, M., & Jhully, S. (Filmmakers). (2003). Rich media, poor democracy [Video]. Media Education Foundation. https://centennialcollege.kanopy.com/video/rich-media-poor-democracy&inst=centennial

Statistics Canada. (2020, June 5). Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-20-0001/142000012018001-eng.htm

Stereotype. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/stereotype

Sunuwar, D. K. (2019, September 19). Indigenous Media Caucus amplifies Indigenous voices globally. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/indigenous-media-caucus-amplifies-indigenous-voices-globally

TEDx Talks. (2015, February 19). Breaking down stereotypes using art and media | Bayete Ross Smith | TEDxMidAtlantic [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zyqcuQVafk

TEDx Talks. (2017a, April 19). How big data can influence decisions that actually matter [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C6WKt6fJiso

TEDx Talks. (2017b, May 17). Whoever controls the media, the images, controls the culture: Min Kim at TEDxLehighU [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpjWioF6iMo

The Guardian. (2019, May 7). Big data: why should you care? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ji18sDbWI_k&feature=youtu.be

The Media Insider. (2019, November 8). Stuart Hall’s representation theory explained [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJr0gO_-w_Q

The Verge. (2018, June 11). Net neutrality is dead: Now what? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hIULYHz6BWA

Thompson, K. (2019, October 1). Media representations of benefits claimants. ReviseSociology. https://revisesociology.com/2019/10/04/media-representations-of-benefits-claimants/

Wang, R. A. (n.d.). 10 most censored countries [Report]. Committee to Protect Journalists. https://cpj.org/reports/2019/09/10-most-censored-eritrea-north-korea-turkmenistan-journalist.php

Winseck, D. (2018, December 11). Media and Internet Concentration in Canada Report 1984 – 2017. Canadian Media Concentration Research Project (CMCRP). doi:10.22215/ cmcrp/2018.2. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/110.nsf/vwapj/972_CMCRP_MediaandInternetConcentration1984-2017.pdf/$file/972_CMCRP_MediaandInternetConcentration1984-2017.pdf

Women in View. (2019, May). Women in View: Onscreen Report. [Report] Women in View. http://womeninview.ca/reports/

Wong, T. (2019, September 25). Majority of Canadians want government to regulate social media, poll says. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2019/09/25/majority-of-canadians-want-government-to-regulate-social-media-poll-says.html

UNESCO. (2021, May 7). Journalism, ‘Fake News’, and Disinformation: A Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. https://en.unesco.org/fightfakenews

Social Analysis Example

Social structures and institutions are a way of organizing society and creating patterns of social behaviour. As we have learned, the media reinforces dominant ideologies. Because of this, it is important to approach a social analysis of media using the following questions:

Who has created the message? Why? Who benefits from this message? Who loses? What techniques are used to attract my attention? How might different people understand this message differently from me? What are the roles, norms, and expectations communicated by this message? What is being left out, hidden, or omitted altogether? What types of representations are considered valuable or desirable, and which are not? How has media influenced what I believe, how I think, and how I behave?