In what other ways might globalization have contributed to how the COVID-19 pandemic progressed?

Globalization and Global Citizenship

Soudeh Oladi

What is Globalization and Global Citizenship?

Globalization has become a one-word-fits-all concept. Put simply, it acknowledges that we are becoming increasingly connected economically, culturally, and politically. We can see this shift in our everyday lives. Think about how quickly you can receive news about events in another country. Consider how a social movement in one country (for example, Black Lives Matter in the US) can spark protests around the world. Think about where your food comes from—or how massive companies like Amazon crisscross the globe, producing, sourcing, and selling products. All these are examples of globalization in action.

Globalization and capitalism are closely linked. Capitalism requires new markets, places in which to buy and sell products. Globalization provides such markets (Awan, 2016). As you will see in this module, some of the criticisms and defenses of globalization overlap with those of capitalism. For example, defenders of capitalism point out that there has never been a better economic system for creating wealth, leading people out of poverty, and improving quality of life. But critics warn that unchecked capitalism disempowers workers and leads to greed and corruption on a massive scale.

A commonly used term to describe globalization is global village. In a village, one person’s actions can affect everyone else. This is why it is important to consider the effects of globalization. For example, what role did globalization play during the COVID-19 pandemic? You might start by considering negative effects—like how the ease of international travel caused the virus to spread. You may also note how emerging crises tend to unveil the extreme injustices and inequalities of economic and social systems. But also consider hopeful effects—such as how scientists were able to collaborate to produce vaccines more quickly than ever before.

In the unit on globalization, we will explore the different waves of globalization, multiculturalism, cosmopolitanism, and what it means to be a global citizen.

Globalization: A History

In our lifetime and in our parents and grandparents’ lifetime, there have been three waves of globalization (Rumford, 2008).

The first wave can be traced back to the 1870s. That lasted until the First World War. Industrialization was well underway at that time, and advances in transportation meant less trade barriers and more globalization of trade (Hill, 2012). Prosperity in some parts of the world led to the migration of more and more people. During this period, nearly 10% of the world’s population migrated to new territories (Maddison, 2007).

The first wave of globalization has a legacy in colonization. Many of the trade measures that are in place today can be traced back to the colonial structures of that time, when groups in power wanted to ensure they would always benefit and maintain their superiority.

For three decades starting in 1920, most economies faced major crises, and globalization slowed down (Lewis & Moore, 2009). But before long, the world entered the second wave of globalization (1950–1980). During this time, many economies picked up where they left off and grew at a rapid pace. New trade agreements and cartels like OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) were formed during that time period to encourage a global economy (Wallerstein, 2008).

The third wave of globalization started in the early 1980s. Advances in communication technologies made this stage evolve quickly. Many countries could not resist global trade associations such as the World Trade Organization and opened up their economies for global business (Stiglitz & Pike, 2004).

When we think about globalization, a new sense of community and locality comes to mind, where the world is interconnected and unified. But four decades later, critics are warning that the third wave of globalization has exploited the working class, caused more harm than benefit for developing economies, and ultimately made the rich richer and the poor poorer (Kunnanatt, 2013; Klein, 2007).

An important question many people are asking is if globalization in its current form (third wave) is the only feasible option for us right now.

Those who answer yes likely believe in “globalization from above.” Also called corporate globalization, “globalization from above” is driven by big business. It mainly serves the interests of transnational corporations and monetary institutions like the World Bank that work in collaboration with the most powerful economies in the world (Demaine, 2002). These corporations and institutions have made a lot of money off third-wave globalization and want it to continue.

But there are also those who believe in “globalization from below.” These include social movements, non-government organizations, and people who are active in grassroots initiatives and community-based movements. These people want to open up spaces for community building and meaningful participation in democracies.

Critics have pointed out that third-wave globalization has led to greater social exclusion and marginalization (Santos, 1998). Those who believe in “globalization from below” counter this through bottom-up approaches that represent the interests of ordinary people. For example, by participating in initiatives that “[re-inject] ideas of social justice, human rights and environmental sustainability into the global agenda” (Ife, 1995, p. 5). These movements resist “globalization from above” and offer meaningful alternatives to the models imposed by economic powerhouses and governments that keep the hegemony of the “haves” over the “have-nots” alive and well (Falk, 2013; Smith, 2008).

Citta`Slow

One example of a “globalization from below” response to “globalization from above” is the Slow Movement. This began with the “Slow Food” philosophy in Italy, which was a reaction to the extensive spread of “fast food” (Miele, 2008). It promoted eating local and sustainably grown food, and slowing down to cook and enjoy meals with friends and family. This expanded to become an overall philosophy of slow living.

Citta`Slow, which means “slow city,” is an international network of small towns that have been inspired by the Slow Movement. Now more than 100 countries worldwide are part of Citta`Slow and practicing in the slow-living movement as a measured response to globalization. Slow living has been called a form of “ethical cosmopolitanism” (Parkins & Craig, 2006). In Canada, four towns in British Columbia, Quebec, and Nova Scotia are part of the Citta`Slow movement (Cowichan Bay, Lac-Mégantic, Naramata, Wolfville).

Mullah Nasreddin, a Persian sage who used humour to share his wisdom, was asked to show the centre of the universe. He pointed to the hook on the ground where his donkey was tied. “There,” he said, “there is the centre of the universe—and if you don’t believe me, go and measure the equidistance from it around the world.”

Consider these questions:

- Is it possible for globalization to create one centre for the whole world?

- Can we have a form of globalization that allows for multiple centres?

Go Deeper

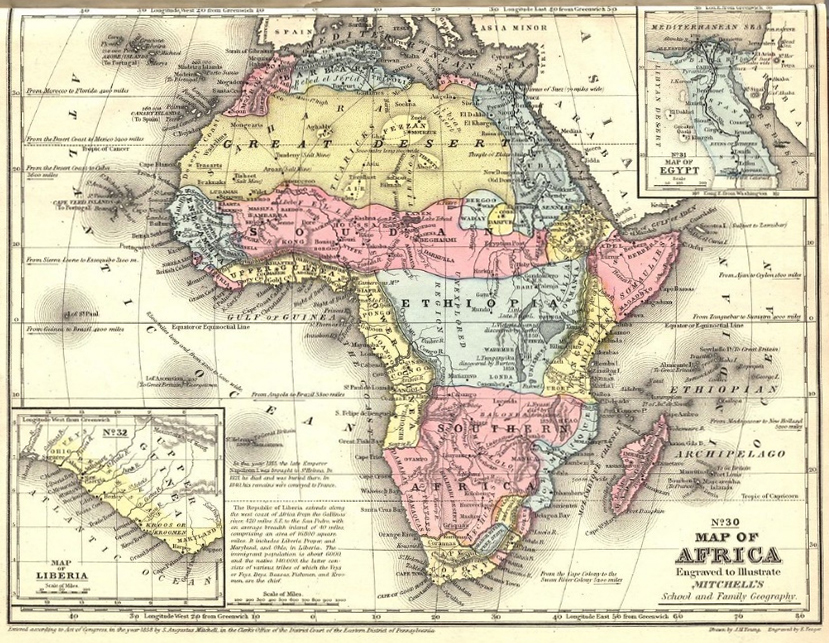

The Scramble for Africa refers to a time known as the New Imperialism period between the 1880s and the start of the First World War. European nations had long exploited African countries. They did this in the name of bringing civilization to Africa. But in reality, European countries were reaping the benefits of Africa by exploiting the land and its inhabitants. During this period, European countries divided Africa up between themselves and even created artificial states without taking into consideration cultural, religious, linguistic, or ethnic issues. In the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, France, and Germany tried to regulate European colonization and trade in Africa. But it was a failure. The involved nations did not agree on how to divide up Africa among themselves. One of the central reasons behind WWI is believed to be the dispute over who got what in Africa (Joplin, 2019).

Watch The New Scramble for Africa to get an idea of how the continent of Africa was taken advantage of and exploited by European powers. (Source: Al Jazeera English, 2014)

Globalization and Cosmopolitanism

When I was growing up in Canada, I would often be asked, “Where are you from?” and I’d say, “Born and raised in Scarborough, Ontario” or “Toronto.” The person asking would try to hide their disappointment at my response. I could see them thinking hard about how to ask the question again without offending me: “No, I mean what’s your background,” they would venture. Of course I knew exactly what response they were fishing for from the first question. But I wanted to know if there would come a day when I would be considered a Canadian without being asked, “But where are you really from?” That day has yet to come.

For many people, including myself, globalization has brought up questions about home and belonging. I often find myself “suspended between the no longer and the not yet” (Braidotti, 2006). I “no longer” only identify with my ancestral “homeland,” but I am still perceived as “not yet” a Canadian.

In trying to locate myself, I have looked closely at concepts like cosmopolitan and global citizen. The word cosmopolitan means “world citizen” and its roots go all the way back to ancient Greece (kosmo-politēs). The Greek words kosmo (the world/universe) and politēs (a citizen) combine to give us cosmopolitan. In the Western tradition, cosmopolitanism has been traced to Diogenes of Sinope, the founder of the philosophy of Cynicism. Diogenes challenged the conventions of Greek society in numerous and often outrageous ways. For example, he lived in a large clay pot in the marketplace of ancient Athens. When he was challenged by Athenians to say where he came from, Diogenes would respond, “Kosmo-politēs!”—“I am a citizen of the world!”

European Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant also informs the modern understanding of cosmopolitanism. He believed that being a cosmopolitan means we have moral obligations towards one another. These moral obligations are rooted in our shared humanity and should not be impacted by our attachments to concepts such as nation, language, religion, or family. Kant expressed the idea that all human beings have an “intrinsic worth” and a “dignity” that must be respected (Kant, 1981). Because of this, we cannot use people and treat them as a means to an end (to produce a result we desire). Kant’s writings about cosmopolitanism came around the same time European countries were colonizing the rest of the world (Kent & Tomsky, 2017). Nowadays, cosmopolitanism means thinking beyond local and national concerns. But in a world that is increasingly becoming interconnected, is this a realistic expectation? Can we say that we are moving towards a borderless world? Or has globalization had the opposite effect: highlighting local and national differences?

Globalization, Migration, and Employment

In our globalized world, people increasingly move to study, live, and work in other countries and communities (Gibson & Koyama, 2011). The number of individuals living outside their original homelands increased from approximately 33 million in 1910 to 272 million in 2019 (Benhabib, 2004; United Nations, 2020). In 2020, India, Mexica, and China had the largest number of migrants living abroad (United Nations, 2020).

To accommodate the growing number of immigrants, many countries have adopted multiculturalism policies. For nearly half a century, Canada’s multiculturalism policies have promised opportunities to immigrants on the basis of merit and hard work.

But this wasn’t always the case.

Renisa Mawani (2010) writes that at the start of the 20th century, colonial states like Canada put in place laws and policies to regulate perceived threats. In Canada, these “threats” included Indigenous Peoples, Japanese and Chinese labourers, and mixed-raced populations. For example, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 stopped almost all Chinese immigrants from coming to Canada. It would be 24 years before this policy was repealed (ended).

In the late 1950s, after the end of World War II, multiculturalism began to emerge as an official policy in Canada. Throughout the 1960s most new immigrants to Canada were from European countries (Italy, Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, Greece, Australia, France, and Portugal) (Lee, 2013). But as Europe became more economically stable after WWII, fewer European immigrants wanted to come to Canada. The country had no choice but to look to non-European (in particular, non-white) nations for new immigrants.

Canada’s Multiculturalism Act, passed in 1988, promised to promote respect and uphold the differences in ethnicities, cultures, religions, languages, and heritages of Canada’s citizens. The act was originally established as Canadian policy in 1971 by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

In 2002, Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government adopted the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which included the category of “economic immigrants” (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2014). Canada’s interest in economic migrants is primarily aimed at pursuing “the maximum social, cultural, and economic benefit of immigration” and “to support the development of a strong and prosperous Canadian economy” (Government of Canada, 2001). According to Canada’s immigration minister, the federal government plans to bring in more than 1.2 million new immigrants between 2021–2023 to fill gaps in the labour market and boost an economy that has been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. For Canada, these will be the highest years on record for accepting immigrants since 1911. By 2036, nearly half of Canada’s population is expected to be an immigrant or the child of an immigrant (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Globalization has its success stories, but it also often generates demand for low-paid service workers who are mostly women, new immigrants, and people of colour. These workers fall into a new category called the “serving class” (Sassen, 2010). Even though Canada recruits skilled professionals through its immigration programs, many end up underemployed in low-paying and precarious jobs (Allan, 2014). A study published by Citizenship and Immigration Canada entitled Who Drives a Taxi in Canada? found that overqualified immigrants, including architects, engineers, and physicians, drive taxis. Immigrants from India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Haiti and Iran were significantly overrepresented among taxi drivers (Xu, 2012).

Underemployed immigrants is one of the negative side effects of globalization. One important question we might ask ourselves when we think about globalization is: How can we navigate and negotiate between its good, bad, and ugly sides? Listen to the summary of a short story by Ursula Le Guin (1973) and reflect on this question.

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas is a story about a utopia. In this town, the people want for nothing. They celebrate and dance and embrace each other. The animals, children, and land are well looked after. The air is fresh and clean and filled with the sounds of beautiful music. The people of Omelas live in bliss, though they are not unintelligent. All of the people who live in this beautiful place know that their happiness and enjoyment is contingent on the incessant suffering of a lone child, kept out of sight in some small, rarely visited room. All of the people who live in Omelas know about the child and they know that the child must suffer in order for the rest to have what they need. The people of the city learn of the child’s existence in their youth and often rationalize to themselves that there is nothing they could do to help the child, and while it’s awful that it has to suffer, the suffering is what allows for the beauty and bounty of the city for everyone else. Some, however, cannot stay in the city once they learn of this secret and they choose to walk away, into the night, onward in a new direction.

Questions

- Does globalization require us to ignore the misery of some so we might continue to benefit ourselves?

- Can you identify similar cases in your life when you ignored a glaring injustice or just walked away from it because there was nothing you could do?

Globalization, Global Citizenship, National Citizenship

There is no more dynamic social figure in modern history than The Citizen.

– Ralf Dahrendorf (1974)

Philosophers in the ancient world shared many ideas about what global citizenship should involve. These early philosophers were united by a belief in the shared humanity of all persons. Global citizens since the time of Diogenes have believed that there are many acceptable ways to live.

The spirit of global citizenship has appeared in different ways throughout history. Until the 16th century, much of South and Southeast Asia were united by language and the activities of traders, writers, religious figures, and adventurers. There was a similar period of cultural flourishing under the Islamic Abbasid Dynasty, which stretched from the Middle East and Persia to North Africa and Spain. Philosophy, science, mathematics, and literature thrived in a cosmopolitan environment that allowed for diverse languages, religions, and ethnicities. Global citizenship was also experienced in the great multicultural centers of the Ottoman Empire, including Istanbul, Aleppo, and Baghdad, where people from all faiths and ethnicities lived and worked together (Riedler, 2008; Zubaida, 2010).

In search of a unified definition of global citizenship, scholars and writers have agreed on common topics that fit under its umbrella. Such topics include:

- economic fairness

- equitable distribution of resources

- education

- poverty relief

- cultural identity

- environment

- human rights

- health

- gender equality

- globalization

- social entrepreneurship

- social justice

- sustainable economic development

- corporate responsibility towards one another as global citizens (United Nations, n.d.).

Centennial College’s Institute for Global Citizenship and Equity has its own definition of global citizenship:

To be a citizen in the global sense means recognizing that we must all be aware of our use of the world’s resources and find ways to live on earth in a sustainable way. When we see others are treated without justice, we know that we are responsible for trying to ensure that people are treated justly and must have equitable opportunities as fellow citizens of this world. We must think critically about what we see, hear and say, and make sure that our actions bring about positive change. (Centennial College, 2008)

But what is citizenship? Picture citizenship as a “social glue” that connects people to one another and to a particular territory (Yarwood, 2016). This image differs from a historic understanding of citizenship. For the longest time, a citizen was defined in relation to “nation-state boundaries” (Fischman & Haas, 2012). That is, a citizen was a recognized subject of a country.

The concept of a “citizen” goes back to the Latin civis or civitas, meaning a member of an ancient city-state (Isin & Turner, 2002). The traditional citizen was someone who contributed to public life, including participating politically, while living in the city (Yarwood, 2016; Bellamy, 2008; Janoski & Gran, 2002). For the Greeks, citizenship was linked to the territory of a particular city-state and could not be transferred from one person to the next.

Citizenship can also be understood historically as an instrument of inclusion and exclusion (Mackert & Turner, 2017). We cannot forget that citizenship is a status given to people at different times for different reasons. For instance, citizenship was often slow to be granted to groups of people that were categorized as inferior by the dominant class. Most of what we know of history has been told from the perspective of the included (citizens) and not the excluded (aliens, outsiders, the other) (Janoski & Gran, 2002).

While there are differences between citizenship, global citizenship, and national citizenship, it is useful to note that these concepts are complementary. For instance, identifying as global citizens does not mean we don’t value our national citizenship. It simply means that we assume greater responsibilities for and engage with local and global communities. National citizenship is obtained through birth or naturalization and includes shared national values along with obligations such as paying taxes and following the law. When we think of national citizenship, we think of the rights, privileges, and responsibilities associated with living in a particular country. Citizens fulfill their obligations to the state and in turn the state fulfills its duty by providing protection, education, health care, and access to jobs and resources.

Nowadays, with millions of people living in several nations, many with multiple citizenships, the term citizenship has taken on new meanings. (Castles & Davidson, 2000). It is no longer as much about being connected to a particular territory (Fleming et al., 2018). In the modern world, citizenship fosters feelings of belonging, identity, responsibility, and protection. The contemporary notion of citizenship is about “helping your neighbour; supporting known and unknown ‘others’ in your local area; having a connection and shared understanding with people across your nation; feeling a sense of humanism and attachment to communities across the globe” (Anderson et al., 2008, p. 34).

Key Concepts

Key Concepts

capitalism

A global economic system in which private people and companies own goods and property. The capitalists’ main aim is to produce goods to sell at a profit by keeping the cost of labour and resources low.

cartel

A cartel is formed when businesses agree to act together instead of competing with each other, all the while maintaining the illusion of competition. A cartel is a group of independent businesses whose concerted goal is to lessen or prevent competition” (Government of Canada, 2018).

citizenship

Refers to social and political relations among people who are considered to be community members. It can also refer to borders, passports, and nationalities that divide membership communities from the rest of the world. In the latter form, citizenship labels some people as “national members and others as national outsiders and limits the entry of those outsiders into the national territory” (Bosniak, 2006, p. 2450).

colonization

Occurs when a new group of people migrates into a territory and then takes over and begins to control the Indigenous group. The settlers impose their own cultural values, religions, and laws, seizing land and controlling access to resources and trade.

cosmopolitanism

Belonging to all the world; not limited to just one part of the world. To be free from local, provincial, or national ideas, prejudices, or attachments.

global citizenship

A concept based on social justice principles and practices that seeks to build global interconnectedness and shared economic, environmental, and social responsibility.

globalization

The increasing integration of world economies, trade products, ideas, norms, and cultures in ways that affect all individuals as members of the global community (Albrow & King, 1990; Al-Rodhan & Stoudmann, 2006).

global village

The idea that the entire world is becoming more interconnected because of advances in technology. This makes it possible to deal with the world as if all areas of it were local.

hegemony

The process of building consent through social practices where the ruling classes present their interests as the general interests of the society as a whole.

multiculturalism

The “practice of creating harmonious relations between different cultural groups as an ideology and policy to promote cultural diversity” (Anzovino & Boutilier, 2015, p. 3).

national citizenship

Legal membership in a country typically due to birth or naturalization, which comes with certain responsibilities towards the state and country in question. In exchange the state fulfills certain social responsibilities (access to healthcare, education, etc.) towards its citizens.

naturalization

In Canada, naturalization happens when an immigrant attains citizenship status. The basic requirements to obtaining a Canadian citizenship include permanent residency status, knowledge of English or French, and basic knowledge of the history and sociopolitical makeup of Canada. Naturalized citizens have the same rights as Canadian-born citizens, which include the right to vote, hold public office, and serve on a jury (Canada Statistics, 2011).

precarious jobs

Refers to work that is part-time and/or temporary. Precarious employment means job insecurity, unpredictability in terms of schedule and income, limited control or autonomy as an employee, and lack of regulatory protections, benefits, and entitlements such as paid sick leave, a minimum wage, and protection against unfair dismissal (Goldring & Joly, 2014; Cranford et al., 2003).

social entrepreneurship

A commerce model that combines the principles of business with the objectives of social action and charity

Global Indigenous Example

Historically, there has always been a connection between land and citizenship. When the colonizers wanted to strip the colonized of citizenship rights, one way they did this was by labelling their land as available to be used and owned by others.

“Aboriginal Images Adelaide Museum Reflections #dailyshoot” by Leshaines123 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

For instance, in 1788, Australia adopted the doctrine of terra nullius or “nobody’s land.” As a result, the Indigenous peoples of Australia were treated as de facto migrants who could only claim rights as foreigners and not as citizens of Australia. By doing this, European colonizers deprived the Aborigines people of Australia of the rights associated with citizenship (Egin & Bryan, 2002). To push their agenda, the colonizers labelled Indigenous peoples as savages whose “condition serves as a sort of zero in the thermometer of civilization” (Merivale, 1837, p. 87).

It took around 200 years until there was a symbolic referendum in 1967 to amend the Constitution so it didn’t discriminate against Aboriginal people. In 1992, a landmark decision by the High Court of Australia overturned terra nullius and recognized some Indigenous people’s claims to their land.

Go Deeper

Watch this video that looks at Indigenous rights in Australia, four decades after the 1964 referendum. (Source: Deborah Cornwall, 2016)

Summary

This module takes you through the roots and history of contemporary globalization. It draws a connection between globalization and concepts such as multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism. Additionally, the importance of migration in the context of globalization is discussed. Finally, the link between globalization, global citizenship, and national citizenship is brought to light as we continue to build on what it means to be a global citizen.

Global Citizenship Example

The pandemic has changed our lives in countless ways. But will COVID-19 spell the end of globalization? Watch the video from The Economist called Will Covid-19 Kill Globalization? to find out if we are nearing the end of an era. (Source: The Economist, 2020)

Critically Thinking About Globalization

Globalization and Its Ideological Roots

At first glance, globalization seems like a one-size-fits-all concept. Useful and relatively neutral. But upon closer inspection, we can see that globalization has its own ideological roots that need to be examined. All sorts of questions come to mind when trying to pinpoint the ideological underpinnings of globalization. Questions like:

- When did globalization become a household name and why?

- Who benefits most from a globalized world?

- Who benefits least from a globalized world?

- Are there alternatives to globalization?

- How are capitalism and globalization connected?

- Can we aim for a capitalism that cares more about the interests of Main Street (regular people) as opposed to Wall Street (rich people)?

- How is it that individuals like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have grown their wealth by billions during the COVID-19 pandemic, but millions have been hit by poverty and joblessness?

- The GameStop debacle, where a group of random people on the internet managed to make a big impact on the market, made a lot of rich people worried. Why? (Source: CNET, 2021)

Sources

Licenses

Globalization and Global Citizenship in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action (2021) by Centennial College, Soudeh Oladi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) unless otherwise stated.

Introduction photo by Yeshi Kangrang on Unsplash.

References

This module contains material from the chapter “Global Citizenship: From Theory to Application” by Philip Alailabo, Moreen Jones Weekes, Athanasios Tom Kokkinias, and Cara Naiman, in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action © 2015 by Centennial College.

Albrow, M., & King, E. (1990). Globalization, knowledge and society. London: Sage.

Al-Jazeera English. (2014, July 27). The New Scramble for Africa | Empire [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_KM06hTeRSY

Allan, K. L. (2014). Learning how to “skill” the self: Citizenship and immigrant integration in Toronto, Canada (Doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto, Canada.

Al-Rodhan, N. R. F., & Stoudmann, G. (2006). Definitions of globalization: A comprehensive overview and a proposed definition.

Anderson, J., Askins, K., Cook, I., Desforges, L., Evans, J., Fannin, M., … & MacLeavy, J. (2008). What is geography’s contribution to making citizens? Geography, 93(1), 34–39.

Anzovino, T., & Boutilier, D. (2015). Walkamile: Experiencing and understanding diversity in Canada. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Awan, A. G. (2016). Wave of anti-globalization and capitalism and its impact on world economy. Global Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 2(4), 1–21.

Beck, U. (2003). Toward a new critical theory with a cosmopolitan intent. Constellations, 10(4), 453–468.

Bellamy, R. (2008). Citizenship: A very short introduction. OUP Oxford.

Benhabib, S. (2004). The rights of others: Aliens, residents, and citizens (Vol. 5). Cambridge University Press.

Birkvad, S. R. (2017). The meanings of citizenship: Mobility, legal attachment and recognition (Master’s thesis).

Bosniak, L. (2006). Varieties of citizenship. Fordham L. Rev., 75, 2449.

Braidotti, R. (2006). The ethics of becoming-imperceptible. In C. V. Boundas (Ed.), Deleuze and philosophy (pp. 133–159). DOI:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748624799.003.0009

Canada Statistics. (2011). Obtaining Canadian citizenship. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011003_1-eng.pdf

Canadian Chamber of Commerce (2008). Canadian Experience Class (CEC): Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) Consultations. Canadian Chamber of Commerce report, January 2008.

Castles, S., & Davidson, A. (2000). Citizenship and migration: Globalization and the politics of belonging. New York: Routledge.

Centennial College. (2008). Global citizenship: From social analysis to social action (2nd ed.). Toronto: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2014). Canada facts and figures: Immigration overview temporary residents. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/cic/Ci1-8-10-2013-eng.pdf

CNET. (2021, January 27). The Internet vs. Wall Street: GameStop short squeeze explained [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ZoPEaBAe0CY

Cranford, C. J., Vosko, L. F., & Zukewich, N. (2003). Precarious employment in the Canadian labour market: A statistical portrait. Just Labour, 3. https://doi.org/10.25071/1705-1436.164

Dahrendorf, R. (1974). Citizenship and beyond: The social dynamics of an idea. Social Research, 41, 673–701.

Day, R. J. F. (2000). Multiculturalism and the history of Canadian diversity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Deborah Cornwall. (2016, January 31). Indigenous rights in Australia, 40 years after referendum [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OQb_zvOuPiM

Demaine, J. (2002). Globalisation and citizenship education. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 12(2), 117–128.

de Sousa Santos, B. (1998). Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre: Toward a redistributive democracy. Politics & Society, 26(4), 461–510.

Falk, R. (2000). Resisting ‘globalization-from-above’ through ‘globalization-from-below’. In Globalization and the Politics of Resistance (pp. 46–56). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Falk, R. (2013). The declining world order: America’s imperial geopolitics. Routledge.

Fischman, G. E., & Haas, E. (2012). Beyond idealized citizenship education: Embodied cognition, metaphors, and democracy. Review of Research in Education, 36(1), 169–196.

Fleming, D., Waterhouse, M., Bangou, F., & Bastien, M. (2018). Agencement, second language education, and becoming: A Deleuzian take on citizenship. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 15(2), 141–160.

Gibson, M. A., & Koyama, J. P. (2011). Immigrants and education. In B. A. U. Levinson and M. Pollock (Eds.), A companion to the anthropology of education (pp. 391–407). Walden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Glenn, E. (2000). Citizenship and inequality: historical and global perspectives. Soc. Probs., 47, 1.

Goldring, L., & Joly, M. P. (2014). Immigration, citizenship and racialization at work: Unpacking employment precarity in southwestern Ontario. Just Labour, 22. https://doi.org/10.25071/1705-1436.7

Government of Canada. (2018). What is a cartel? https://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/04262.html

Government of Canada. (2001). Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-2.5/page-1.html

Hill, C. W. (2012). International business (9th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ife, J. (1996). Globalisation from below: Social services and the new world order. In Globalisation from below: Social services and the new world order (pp. 192–196). University of Canterbury.

Isin, E. F., & Turner, B. S. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of citizenship studies. Sage.

Janoski, T., & Gran, B. (2002). Political citizenship: Foundations of rights. In E. F. Isin & B. S. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of citizenship studies (pp. 13–52). Sage.

Joplin, S. (2019). Scramble for Africa. In New World Encyclopedia. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Scramble_for_Africa

Kant, I. (1981). Grounding for the metaphysics of morals (J. W. Ellington, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett.

Kent, E., & Tomsky, T. (Eds.). (2017). Negative cosmopolitanism: Cultures and politics of world citizenship after globalization. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. Macmillan.

Kunnanatt, J. T. (2013). Globalization and developing countries: A global participation model. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 8(4), 42–58.

Lee, E. (2013). A critique of Canadian multiculturalism as a state policy and its effects on Canadian subjects. University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (Doctoral dissertation). https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42631/1/Lee_Emerald_201311_MA_thesis.pdf

Le Guin, U. K. (1973). The ones who walk away from Omelas. In M. Rea (Ed.), Evil and the hiddenness of God (pp. 23–26). Cengage Learning.

Lewis, D., & Moore, K. (2009). The origins of globalization: A Canadian perspective. Ivey Business Journal. https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/the-origins-of-globalization-a-canadian-perspective/

Mackert, J., & Turner, B. S. (Eds.). (2017). The transformation of citizenship, volume 2: Boundaries of inclusion and exclusion. Taylor & Francis.

Maddison, A. (2007). The world economy volume 1: A millennial perspective volume 2: Historical statistics. Academic Foundation.

Mawani, R. (2010). Colonial proximities: Crossracial encounters and juridical truths in British Columbia, 1871-1921. UBC Press.

Merivale, H. (1837). Senior on political economy. Edinburgh Review, 66(133), 73–102.

Miele, M. (2008). Cittáslow: Producing slowness against the fast life. Space and Polity, 12(1), 135–156.

Moore, K., & Lewis, D. C. (2009). The origins of globalization. Routledge.

Pagden, A. (2000). Stoicism, cosmopolitanism, and the legacy of European imperialism. Constellations, 7(1), 3–22.

Parkins, W., & Craig, G. (2006). Slow living. Berg.

Riedler, F. (2008). Rediscovering Istanbul’s cosmopolitan past. ISIM [International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World] Review, 22, 8–9.

Rumford, C. (2008). Cosmopolitan spaces: Europe, globalization, theory. Routledge.

Sassen, S. (2010). A savage sorting of winners and losers: Contemporary versions of primitive accumulation. Globalizations, 7(1–2), 23–50.

Schattle, H. (2007). The practices of global citizenship. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Smith, J. (2008). Social movements for global democracy. JHU Press.

Statistics Canada. (2017). A look at immigration, ethnocultural diversity and languages in Canada up to 2036, 2011 to 2036. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170125/dq170125b-eng.htm

Stiglitz, J., & Pike, R. M. (2004). Globalization and its discontents. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 29(2), 321.

The Economist. (2020, September 30). Will covid kill globalisation? | The Economist [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/KJhlo6DtJIk

Tim Thoughts. (2020, July 21). The ones who walk away from Omelas [Audiobook] | Ursula K. Le Guin [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/fnjyCcfaync

United Nations. (2020). International migration report 2017. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf

UNAI (United Nations Academic Impact). (n.d.). Global citizen education. https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/global-citizenship-education-path-peace-preventing-violent-extremism-and-promoting

Wallerstein, I. (2008). The demise of neoliberal globalization. YaleGlobal Online, 4. https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/2008-demise-neoliberal-globalization

Xu, L. (2012). Who drives a taxi in Canada? Ottawa, ON: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/migration/ircc/english/pdf/research-stats/taxi.pdf

Yarwood, R. (2016). The geographies of citizenship.

Zubaida, S. (2010). Cosmopolitan citizenship in the Middle East. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/cosmopolitan-citizenship-in-middle-east/