What Would You Do?

Do you know where your clothes were made, and by whom? Or what the living and work conditions are for the farmers who grew and harvested the coffee beans in your morning coffee? What if you learned that your clothes are being made for very low wages in an unsafe work environment, or that the production of most coffee impacts the farmers and the environment in negative ways? What would you do?

Go Deeper

One way to try to interrupt the process of labour exploitation and the negative environmental impact of the products that we purchase is to practice conscious consumerism: making purchases that have positive impacts on our society. However, it’s important to consider how much of an impact is made when we try to challenge a system of exploitation from within the very structures that are creating these inequalities.

Read this article to learn more about conscious consumerism. (Source: Wong, 2019)

What Is Social Action?

We don’t have to engage in grand, heroic actions to participate in the process of change. Small acts, when multiplied by millions of people, can transform the world.

– Howard Zinn

This module will explore what global citizenship means in terms of social action, the point at which awareness is put into practice. When “this isn’t fair” becomes “let’s make it fair,” the shift has been made from awareness to action. Social action, then, is any action of an individual or a group that seeks to promote social change on a small or large scale. Social action starts with an awareness of the root cause(s) of a social problem. We can understand why a social problem exists by applying critical social analysis to the issue. We can then use that analysis to take action and work towards fairness and equity.

Anyone can take social action at any level. Individual actions, such as writing an email or re-posting a link online, can start a conversation about problems in our society, and how we might begin making changes. We do not need to be considered an activist to engage in social action. There is more to social action, however, than just a willingness to get involved. Good intentions can sometimes do more harm than good. For example, some of the most vocal and committed individuals work for extremist groups willing to kill to promote their values. This module focuses on social action in the service of social justice—that is, social action that seeks to heal divisions in society, not hurt other people.

Go Deeper

This article, although written with educators and teachers in mind, includes strategies for students, such as sharing your knowledge of social issues to educate others, and engaging in social action through public awareness campaigns, protests, and political advocacy. (Source: “10 Ways Youth Can Engage in Activism,” n.d.)

Why Take Social Action?

If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.

– Desmond Tutu

We take social action because we believe that a social condition is unacceptable and requires change. We may think that there is not much we can do as individuals, but as we will see in this module, people can get involved on the individual level, with groups, and with large social movements. Individual actions, such as choosing to purchase fair trade products and boycotting companies that are exploitative, or reducing your carbon footprint by walking or taking public transit to work or school instead of driving, are good places to start. But when these actions are taken by many towards the same goal—when we engage in collective action—there is strength in numbers. Collective action refers to a group of individuals working together towards a greater cause.

Social action can start with the simplest idea and the willingness to implement it. To address injustices and inequities in our society, we can start by learning about and raising awareness of the structural and ideological foundations that create and maintain social problems. It is important to also examine our own biases and beliefs, as well as the ideologies that inform our worldview when we consider taking action. Social action can often inspire resistance from groups that are benefiting from the status quo and do not wish to see society reorganized, as you’ll see in the sub-topic on backlash.

Go Deeper

Consider how social change can begin on a small scale. Read this article to learn how researchers have identified that it only takes a small minority group of 25% to reach a “tipping point” for social change. (Source: Noonan, 2018)

Challenging Norms—How Social Action Begins

Let’s say you’ve been learning about the controversies over national holidays that are based on colonial history. These debates have got you thinking, and you want to talk about it. Thanksgiving is coming up—one of those holidays at the center of the debate—and you’ve been considering what this celebration represents. It’s always good to discuss new ideas, right…? Read on.

Thanksgiving Dinner

Your family is gathered around the table for your annual Thanksgiving dinner. Everyone is ready to dig into the feast, but you find yourself distracted. Doesn’t this holiday celebrate the origins of colonialism and hundreds of years of violence and oppression? Should we really be mindlessly gorging ourselves on turkey when we are still living this history? What about the people who can’t afford to eat this way, right now? And, oh yeah, who will be washing up when it’s over?

Half an hour into the meal, your aunty notices you’ve been unusually quiet. “You haven’t said much, dear, are you not feeling well?” she asks.

“I’ve been wondering about this Thanksgiving tradition,” you say. “Doesn’t it glorify colonialism and slavery, and the genocide of Indigenous peoples?” The table goes silent. Your uncle freezes with a forkful of food halfway to his mouth. Your mother glares at you in horror. Then it starts.

“It’s just a celebration of the harvest,” says your aunt, exasperated.

“I haven’t oppressed anyone,” your uncle snaps. “Don’t blame me for history.”

“This is not the time and place for politics,” growls your father.

Your brother stares down at his phone. Your cousin points out the factory-farmed turkey on the table, but gets cut-short by your uncle with “don’t you start now.” Your mother pleads, “Can’t we just have one day when we don’t feel guilty about something?”

You silence yourself with a piece of turkey. “I guess I should have kept my mouth shut,” you think.

You’ve just confronted the first challenge of being an activist—defensiveness. You asked hard questions, made people uncomfortable about their privilege and ran headlong into their unconscious biases. It seems you picked the wrong time and place to raise your concerns, but there is never a “right” time or place, because talking about social injustice always meets with resistance. You are faced with a choice—let it drop, live your life, and let someone else fix the world, or keep asking questions and going deeper, because if not you, then who?

“Thanksgiving Dinner” by Paula Anderton, Centennial College is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License.

Backlash to Social Action

As the “turkey dinner” story illustrates, it is difficult to ask people to reconsider their perspective. People like comfort and certainty, and change can make them feel confused and insecure. It puts people on the defensive when the way they do things, or view things, is challenged. But no progress can be made to address injustice without discomfort.

Imagine that dinner-table defensiveness on a larger scale. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, for instance, has become an international effort to end the structural racism that causes Black lives to be valued less in our social institutions. This is big social action and it gets a big response, including fear and anger from thousands of people who have benefited from this unequal system and like it just the way it is. When dinner-table defensiveness is felt by thousands of people, it becomes backlash.

Types of Backlash

Politicians, the media and the police often label social action, which includes both activists and advocacy, as ‘special interests’. But I don’t see anything special about needing to – or at the very least wanting to and trying to, feed the hungry and house the homeless. Social action, at its root, is about fighting for and ensuring the most basic of human rights for all people. (Crowe, 2006)

Backlash can range from words and labels used to undermine social action, to organized violence. Labels like “special interests,” for instance, make social action for change sound like “fringe movements” that only concern a few. The phrase “All lives matter” is commonly used to counter the BLM message, missing the point of the movement. Rioting in the streets and hate groups, like white supremacists, take backlash to the extreme.

Watch this video for an explanation of the backlash phrase “All lives matter” (Source: Peace House, 2016). While the video may be humorous, it makes a real point about how easy it is for people to dismiss an important issue like BLM when it becomes “inconvenient” for them.

It is important to understand the difference between backlash and dissent. To disagree with an opinion, policy or objective is not the same thing as backlash. Backlash happens when the group in power believes that power is being threatened. Backlash is about maintaining privilege and keeping things the way they are—with dominant groups remaining dominant. People engaging in backlash resist change not because of well-reasoned arguments against that change, but because they may lose their advantage in society. Dissent, or disagreement, should always be permitted in a free and open society. In fact, most social movements are based on dissent against some aspect of the system that isn’t fair—it’s how social progress starts. Backlash, however, is an emotional response, often driven by anger or fear, which holds back progress on social problems.

Go Deeper

Backlash in Canada

It’s easy to critique social problems in the United States, where everything seems to happen on a bigger scale and in full view of a global audience. But when we turn the lens on ourselves, Canada is also seeing a disturbing trend of backlash to social action. Take a look at the examples that follow.

Wet’suwet’en pipeline-protest backlash (Source: Fine, 2020)

Alberta’s Bill 1 (Source: CityNews Edmonton, 2020)

Islamophobia in Quebec (Source: “Why this photo of a politician with Malala is being criticized,” 2019)

Types of Social Action: Charity and Social Justice

Social action takes many different forms. Social justice and charity are both forms of social action, but their goals and impact are different.

Social justice usually involves collective public acts to promote social change in institutions and in society. The aim of social justice is to create an egalitarian society based on the principles of equality and solidarity. Such a society understands and values human rights and recognizes the dignity of every human being (Bell, 2007). Social justice is directed at the root causes rather than the symptoms of social problems.

Charity, on the other hand, addresses the symptoms of social problems, but it may not directly address the real long-term needs of people or communities. Charity can take several forms. It may involve acts by individuals or groups aimed at providing for the immediate needs of others through direct services such as serving food and providing shelter. Charitable organizations run services such as homeless shelters and food banks, and set up emergency aid campaigns to deal with specific issues, such as famine relief. All are attempts at responding to injustice and are usually not controversial.

Although such efforts are valuable to those in need, they are limited in scope. Charity does not fix the underlying, systemic problems that create suffering. It does not address structural or ideological issues. For this reason, relying on charity can be disempowering for those who are socially disadvantaged. Only permanent structural changes can eliminate the root causes of social inequalities—and remove the need for charity in the first place.

Social justice work is challenging. It means raising difficult questions about how society is arranged and thinking about the root causes of such problems as poverty, homelessness, or racism. To engage in social justice is to ask, for example, whether people who are wealthy owe something to those who are poor. Such questions are unsettling to those who believe that their good fortune is a product of their hard work and abilities rather than the result of unjust social structures.

Go Deeper

This video offers a satirical look at aid projects to Africa. It uses humour to make a serious point about the shortcomings and stereotypes in the international aid system. (Source: SAIH Norway, 2013)

This TED Talk article discusses an interesting take on the function of charity. Philosopher Peter Singer has proposed a way to make charity into a social movement that makes a difference in the long term, which he calls “effective altruism.” (Source: Ha, 2013)

Grassroots Social Action

Grassroots social action occurs “on the ground” at a local level. It involves community-based activities and projects that improve conditions or change policies. This form of collective action turns awareness of root causes and structural reasons for social problems into direct action. It seeks to right wrongs, and support and engage with the people who are most affected by the issue. Grassroots social action typically begins with the people who are directly experiencing the effects of social inequalities.

The realistic scale, combined with solutions based on the needs, desires and identity of the community, make this kind of social action accessible and beneficial to participants.

Grassroots movements must work for change within the system that created the original problem, which can block progress or limit results. They may also collapse due to competing interests or differences within the communities themselves.

An example of a grassroots social action initiative is Idle No More (INM). INM was started in 2012 by four women in Saskatchewan to address First Nations treaty issues across Canada. This non-violent movement began as a response and resistance to Bill C-45, which was passed through the Senate in Canada in December of the same year. This bill included changes to land management on reservations, removed protections for hundreds of waterways, and weakened Canadian environmental protection laws. Beginning with email threads between the four women, INM gained international attention with a hunger strike by northern Ontario Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence that began in 2012 on International Human Rights Day. The Idle No More movement has spread globally both online and offline to provide a voice for Indigenous land rights, cultures, and sovereignty.

Go Deeper

Watch this video for a brief history of the Idle No More movement in Canada. (Source: CBC News, 2017)

Other Sources

An Indigenous-led Social Movement (Source: “An Indigenous-led Social Movement,” 2020)

Being Idle No More: The Women Behind the Movement (Source: Caven, 2013)

Social Justice Movements

When social action occurs on a broad scale and at the group level, we usually call it a social movement. Social movements vary and are sometimes hard to define, but they share certain characteristics. For one thing, social movements tend to bring together people who are interested in advocating for social change. Social movements often have a distinct collective identity and are structured around a particular goal. Their goals can be either specific or broadly aimed at bringing about social change at the structural level.

Social justice movements take collective action to promote social change in institutions and society. They are focused on the root causes of social problems. This also means addressing the ideologies and institutions that work to oppress marginalized groups. Unlike charity, which provides a temporary “Band-Aid” solution to issues, social justice movements try to transform the political, social, and/or economic system. The changes they seek promote equity and equality, the basis of human rights.

Social justice movements work to fix the structural issues that create and maintain social problems. They challenge the dominant values and beliefs of a society. This includes questioning the ideologies that rationalize those structures as well as the oppressive actions of individuals who participate in them. This level of action changes the way society operates. Movements such as women’s rights, LGBTQ2S+ rights, and racial equality have fundamentally altered society, resulting in human rights laws and social protections.

Social justice movements take time. They involve years of dedicated effort from committed reformers. They also require financial resources and access to media to rally support. In the meantime, social justice movements do not answer the immediate needs of those who suffer from marginalization and injustice. Finally, while changing ideologies and structures is the ultimate answer to human suffering, it requires confronting powerful forces resistant to such change. These forces make it difficult to achieve social justice aims.

CC BY 3.0 license

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) social justice movement was started in 2013 by three women, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. It began as an online platform, called #BlackLivesMatter, to mobilize and organize a response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman. Since then, the BLM movement has expanded globally to include more than 40 chapters. It seeks to protect Black people from the deadly violence they face from police and institutions. It also draws attention to and addresses systemic racial discrimination.

Go Deeper

Learn more about the origin story and work that continues in the BLM movement. (Source: Herstory, 2019)

The Canadian chapter of Black Lives Matter seeks to dismantle anti-Black racism in Canada, with a call for solidarity within Black communities and with Indigenous groups. Read more about the Canadian chapter. (Source: Black Lives Matter – Canada, n.d.)

Watch this interview with one of the founding members of the Black Lives Matter movement, Patrisse Cullors, to learn more about the history and future of BLM. (Source: Time, 2018)

International Aid and Social Entrepreneurship

So far, we’ve been learning about social action that happens at the level of groups and communities, and that directly involves the people who are most affected by the issues. This social action tends to occur outside of the system and works to eradicate the systemic and structural causes of social problems. But we might ask: Can social justice be achieved from within existing structures and institutions? Is it possible to have meaningful social action within the very systems that create and contribute to social issues? When we consider these so-called “top-down” approaches to social action, two examples are useful to critique: international aid and social entrepreneurship. These approaches do not necessarily seek to change systems, and are not rooted in transformative ideologies. Instead, they operate using social structures and institutions that are already in place and are largely informed by dominant ideologies and values, such as neocolonialism and capitalism.

International aid is an example of top-down social action that crosses national borders. It is often called international development or foreign aid. International aid involves loaning money on a large scale to struggling countries. Most international aid is provided with an agenda. Countries that accept the aid are forced to adopt “Western” style industrial economics and join the global market economy.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are non-profit organizations that engage in grassroots projects and international aid. They are not run or funded by governments. A common critique of NGOs doing international aid work is that they do not consult or collaborate enough with the people they aim to help. This can produce “Westernized,” patriarchal solutions that might not be a good fit with the values, traditions, and desires of the people receiving the aid. Watch the TED Talk “Want to Help Somebody? Shut Up and Listen!” to see how good intentions don’t always get good results (Source: Sirolli, 2012).

Social entrepreneurship, on the other hand, is a business model that aims to generate both profit for the company as well as social benefits for those in need. It is also known as social enterprise and corporate social responsibility. It involves large companies conducting business with social consciousness. This might include minimizing negative impacts like exploiting labour or damaging the environment. Businesses both large and small can also have charitable programs through which they donate a portion of their profits to social causes.

Social entrepreneurship can work within the current economic system in a way that benefits workers, communities and the environment. This makes it practical and sustainable. Because it does not threaten existing power structures, it is less likely to face resistance (compared to, for example, grassroots movements).

Critics claim that profit is still the priority. Ethical business practices are used as a marketing tool. Therefore, social entrepreneurship does not signal a shift in ideology. It does not create structural change but functions within the larger system of exploitation, so it is not a lasting solution.

Go Deeper

Watch this video to learn more about entrepreneurs and businesses that are focused on addressing sustainable solutions to social problems. (Source: Latitude33, 2015)

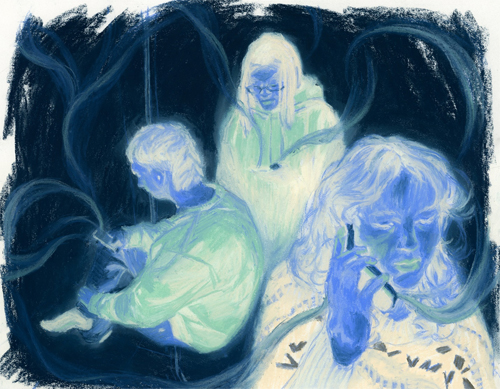

Online Activism

Activism—social justice work—has always involved committed people devoting time and effort to a cause. This often includes “boots on the ground” activities, like protesting, rallying, going door to door, attending public meetings and pressuring politicians, to name a few. But the internet and social media have changed the nature of social action. Now there are alternatives to the “direct action” of conventional activism. Online petitions and “awareness campaigns” about social justice issues require little more from us than a click of the mouse or a small donation. But is “awareness” social action? Does it have the power to actually change anything?

Clicktivism

Online social action or “ clicktivism” uses the internet to rally support for causes. This might involve petitions, “favoriting,” or re-posting content about social justice issues. Also known as “hashtag activism,” these social media–driven “awareness” campaigns publicize social justice issues as a first step in promoting social action.

For most online campaigns, the commitment expected is minimal. Because of this, online activism has been critiqued as “slacktivism,” not activism. Critics also point out that clicktivism is often used as virtue signalling on social media. In other words, people participate in order to appear committed or enlightened, not because they really care about the cause.

Sharing social justice issues on the internet leverages the power of millions of online users to raise awareness and drive change. Petitions conducted through the internet have resulted in significant gains for social justice. Like-minded activists can find each other and organize quickly, while people who were unaware of social problems outside their communities are exposed to issues from around the world.

Traditional activists dismiss clicktivism as an agent of social change because it poses no threat to the dominant power structure—which controls the very platforms where clicktivism happens. There is also the temptation to believe that one has fulfilled their social obligations to global citizenship by merely clicking petitions. This shallow level of engagement and commitment cannot entirely replace “on-the-ground” activism.

Watch this TED Talk by Zeynep Tufekci for a perspective on the benefits and limitations of internet-driven activism (Source: TED, 2015). She looks at various political and social justice movements from around the world and makes a strong case for using social media to rapidly mobilize real action, on the ground. She also points out that these quickly formed protests have a poor track record of actual results. Using the example of the US Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, she demonstrates that “slow and sustained” social movements, with dedicated, long-term participation, achieve political change. Politicians need to see that a movement is not going away before they take it seriously.

Go Deeper

Here are some quick-viewing sources for more perspective on online activism:

Read this story about how an online petition successfully pressured a Florida school board to change the name of a school named after a well-known racist. (Source: Richmond, 2013)

Watch this video about the “Ice Bucket Challenge,” a successful online campaign to fund research on the rare disease ALS. (Source: History NOW, 2017)

Watch this video from Seeker to see how slacktivism can actually harm charities and movements by reducing participation. (Source: Seeker, 2013)

Watch this video from The Feed SBS (an Australian public broadcasting service) for a critique on why clicktivism is not a replacement for traditional activism. (Source: The Feed SBS, 2013)

Activism, Allyship, and Advocacy

Expressing oneself is a part of being human. To be deprived of a voice is to be told you are not a participant in society; ultimately it is a denial of humanity.

– Ai WeiWei

The terms activist, ally, and advocate are sometimes used interchangeably, but there are differences. The differences can be found in the individual’s level of engagement with social problems and marginalized communities.

An activist participates in social change work. Sometimes this is full-time, paid work; sometimes it is part-time and unpaid. What distinguishes an activist from someone who simply supports a cause is their level of engagement. Activists are willing to commit significant time and effort to a cause. In some parts of the world, they take considerable personal risk when their social action challenges those in power. An activist often fights against injustices from outside of the structural system (while an advocate may work from within). For example, an activist may rally supporters to organize a protest that will disrupt the daily commute on a major highway in order to capture the public’s attention for their cause. An activist may also engage in forms of creative communication such as creating visual art, performance, or music to spread a message for change (see the Go Deeper section).

Advocacy may take the form of someone speaking on behalf of communities through legal activity, or speaking on behalf of an individual who requires support. An advocate is perhaps most effective when they can acknowledge and use their position of privilege to speak on behalf of others whose voices may not be heard. An advocate will sometimes have personal experiences with the communities and individuals they support, but not always.

An ally, on the other hand, may not specifically be associated with or belong to a marginalized group, but does support a group’s struggles for equality and social justice. Allyship, for example, is sometimes associated with those who are in support of LGBTQ2S+ communities. Although allies may not be in a position to speak on behalf of this community, they are openly supportive of LGBTQ2S+ peoples’ rights and freedoms. Activism may involve both allyship and advocacy, but activists generally have a direct relationship and lived experience with the communities on whose behalf they are acting for social change.

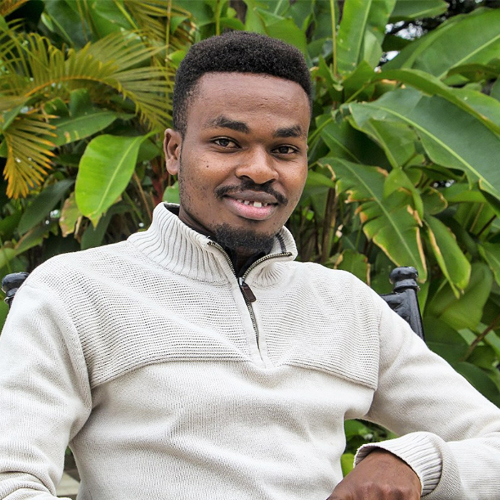

In this TED Talk, Kofi Hope, a Toronto-based social entrepreneur and activist, explores how an individual working with a community can create positive social change (Source: TEDx Talks, 2020). He talks about his work with Black youth in Toronto during 2005, the “year of the gun.” Like today, Black communities at the time were coping with gun violence and racial profiling. He stresses that “hope lives in community” and that we must work together to resist power. “Getting into good trouble” means choosing a cause, finding a community, and starting with an easy and early win. Even small shifts in power can be the first step towards change.

Go Deeper

In this article, activist and teacher Sharif El-Mekki argues that activism and advocacy cannot be separated. The author writes that his personal experiences with racialization have informed his activism and advocacy on behalf of racially marginalized students and communities. He states that advocacy is most impactful when it serves people directly and when it acts with, not just on behalf of, communities. (Source: El-Mekki, 2018)

“Artistic activism” uses art to create connections and evoke a response from an audience. When used to communicate a need for social change, artistic activism expresses values that are shared by communities. Read this article for nine reasons why art as activism can be highly effective. (Source: The Center for Artistic Activism, 2018)

What does it really mean to be an “ally”? Some activists are critical of this word and prefer to think of allyship as involving fellow comrades, or even “co-conspirators.” Others see allyship as a relatively easy way to say you agree with a cause and support the fight for equality. But perhaps it’s too easy. People might think being an ally is enough—and take a pass on any meaningful, direct action. In contrast, perhaps if we saw ourselves as co-conspirators, we might start to show true solidarity—where we work through our feelings of guilt or shame about our privilege, and start taking responsibility for the power that we have to change conditions.

Take a moment to reflect on your level of commitment: Do you consider yourself an ally or perhaps a co-conspirator? What are you willing to risk, or what privileges might you be willing to give up for a cause?

Read the following articles if you would like to learn more about critiques of the term allyship.

Ally or Co-conspirator? What It Means to Act #InSolidarity. (Source: Move to End Violence, 2016)

White People Say They Want to Be an Ally to Black People. But Are They Ready for Sacrifice? (Source: Smoot, 2020)

Global Citizenship and Social Action

None of us are free if one of us are chained.

– Solomon Burke, from the song “None of Us Are Free”

This course has covered a lot of ideas. We’ve looked at big, important concepts for understanding why the world works the way it does—good and bad—and our place in this global community. Social action is the final section of this online textbook because this is where all those concepts connect to global citizenship. The information you’ve read about ideology, identity, power and privilege, media literacy, etc., is important to know to be well-informed and ready to face the world, but it’s only a starting point.

We can be carried along through life hoping the forces of inequality, climate change and injustice don’t affect us. We may think that a good job after graduation will shield us from needing the information in this text. But if you’ve learned anything in a course called “Global Citizenship,” it’s that the forces shaping this world affect all of us, together. This is true on both an economic level, as explained in the module on globalization, and on a social level, where our destiny as a species will be determined by how well we can co-exist with one another.

Living with fairness, sustainability and compassion is not naïve, wishful thinking. These values are necessary for the survival of humanity and our planet. To stay aware of social problems and do something within our means to do is not asking too much of ourselves. Being a global citizen is no longer a choice—it’s an automatic by-product of our interconnected world. We are all contributing to the globalized economy and watching each other on the World Wide Web. The question isn’t whether you will be a global citizen but what kind of global citizen you will be.

There are young activists all over the world tackling social problems on every level. Most of them will never be covered in our media. It is important to acknowledge that even in the field of social action, we tend to be ethnocentric and ignore the work being done in other parts of the globe. For instance, while Greta Thunberg is a hero in the youth climate change movement, there are young climate change activists working in other parts of the world, many before we ever heard Greta’s name, and we don’t know about them.

Go Deeper

Read this article from The Guardian for a perspective on global youth activism and the need to create true global citizenship by recognizing social action efforts around the world. This article asks us to consider our own privilege and ethnocentrism when we think about activism. (Source: Unigwe, 2019)

Read more about two of the global activists in this article by clicking their pictures, below.

Follow the links to see more activists from The Guardian article:

Meet India’s Teen Climate Advocate: Ridhima Pandey (Source: Varagur, 2019)

In India, a Trio of Unlikely Heroes Wages War on Plastic (Source: Associated Press, 2018)

Environmental and Indigenous Rights Activist to Receive WWF’s Top Youth Conservation Award (Source: Naware, 2018)

The Indigenous Teen Who Confronted Trudeau about Unsafe Water Took on the UN (Source: Nagle, 2019)

School Strike for Climate: A Day in the Life of Ugandan Student Striker Leah Namugerwa (Source: EDN Staff, 2019)

Factbox: In Greta’s Footsteps: 10 Young Climate Activists Fighting for Change (Source: Elks, 2019)

Summary

In this module, we defined social action for positive change and identified different approaches to taking social action. We explored charity and social justice movements, online activism, grassroots and top-down approaches, and how and why backlash to social action occurs.

Key Concepts

Key Concepts

activist

An individual who devotes time to work, either paid or unpaid, to bring about social change.

advocate

An individual whose privileged position allows them to speak on behalf of others experiencing inequality, often through legal or institutional activity.

ally

An individual who may not belong to a marginalized group but supports their struggles for equality.

charity

Aid given to those in need. This could be done on an individual basis or it could involve an institution or organization engaged in relief services.

clicktivism/hashtag activism

Online “awareness campaigns” that use the internet to rally support for causes with methods like petitions, “favoriting,” or re-posting content about social justice issues.

collective action

Organized group action towards a common goal.

fair trade

An ethical business model where producers and labourers are paid a living wage and work in safe and humane conditions, and products are made using environmentally sustainable methods.

grassroots

A bottom-up approach to social action, where community members at the local level are directly involved and encouraged to contribute to sustainable positive social change for their community.

international aid

The transfer of resources such as money, goods, and/or expertise from a country or large organization to a recipient country in order to help them emerge from poverty. Also known as foreign aid or development.

social action

Action by an individual or group of people directed towards creating a better society. Social action often involves interactions with other individuals or groups, especially organized action with the goal of social reform.

social entrepreneurship

A commerce model that combines the principles of business with the objectives of social action and charity

social justice

The full and equal participation of all groups in an egalitarian society, where people’s needs are met, and members are physically and psychologically safe (Bell, 2007, p. 1). Social justice aims to address inequities by changing the structural and root cause(s) of social problems.

social movement

A group of people with a common ideology who try to achieve common goals. Social movements can also be described as organized groups of people who may encourage or discourage social change.

virtue signalling

The action or practice of publicly expressing opinions or sentiments intended to demonstrate one’s good character or the moral correctness of one’s position on a particular issue.

Sources

Licenses

Social Action for Social Change in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action (2021) by Centennial College, Paula Anderton and Sabrina Malik is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) unless otherwise stated.

Introduction photo by Isaiah Rustad on Unsplash.

References

This module contains material from the chapter “Making a Difference Through Social Action” by Paula Anderton with Rosina Agyepong, in Global Citizenship: From Social Analysis to Social Action © 2015 by Centennial College.

An Indigenous-led social movement. (2020, February 4). Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://idlenomore.ca/about-the-movement/

Associated Press. (2018, June 4). In India, a trio of unlikely heroes wages war on plastic. National Observer. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2018/06/04/news/india-trio-unlikely-heroes-wages-war-plastic

Backlash. (2020). In Oxford Learners Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/american_english/backlash

Bell, L. A. (2007). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook (pp. 3–15). New York: Routledge.

Black Lives Matter – CANADA. (n.d.). Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://blacklivesmatter.ca/

Cadwalladar, C. (2013). Inside Avaaz: Can online activism really change the world? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/17/avaaz-online-activism-can-it-change-the-world

Caven, F. (2013, March 1). Being Idle No More: The women behind the movement. Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/being-idle-no-more-women-behind-movement

CBC News. (2017, December 10). How Idle No More sparked an uprising of Indigenous people [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/TYf75dKON6k

Change.org. (2015, June 22). Change.org: Reasons for signing [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UcT1rgZDko4

Christiansen, J. (2009). Four stages of social movements: Social movements and collective behaviour. In Research Starters: Academic topic overviews. https://www.ebscohost.com/uploads/imported/thisTopic-dbTopic-1248.pdf

CityNews Edmonton. (2020, July 12). Albertans gather to protest Bill 1 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/–ghwl5chKI

Conley, D. (2013). Collective action, social movements, and social change. In You may ask yourself: An introduction to thinking like a sociologist (3rd ed., pp. 699–725). New York: W.W. Norton.

Crowe, C. (2006, June 2). Why is advocacy or social action important? http://tdrc.net/resources/public/Crowe_Speech_june_02_06.htm

EDN Staff. (2019, June 6). School strike for climate: A day in the life of Ugandan student striker Leah Namugerwa. EARTHDAY.ORG. https://www.earthday.org/school-strike-for-climate-a-day-in-the-life-of-fridays-for-future-uganda-student-striker-leah-namugerwa/

Elks, S. (2019, September 27). Factbox: In Greta’s footsteps: 10 young climate activists fighting for change. Thomson Reuters Foundation. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-youth-factbox/factbox-in-gretas-footsteps-10-young-climate-activists-fighting-for-change-idUSKBN1WC1ZA

El-Mekki, S. (2018, September 24). Educational justice: Which are you – an advocate, ally, or activist? The Education Trust. https://edtrust.org/the-equity-line/educational-justice-which-are-you-an-advocate-ally-or-activist/

Fine, S. (2020, February 25). Alberta tables bill that would jail pipeline protesters for up to six months, impose major fines. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/alberta/article-alberta-tables-bill-that-would-jail-pipeline-protesters-for-up-to-six/?_ga=2.251312902.1875510080.1601920519-100047178.1601920519

Gladwell, M. (2010). Why the revolution will not be tweeted. New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell

Ha, T-H. (2013, March 1). Effective altruism: Peter Singer at TED2013. TEDBlog. https://blog.ted.com/effective-altruism-peter-singer-at-ted2013/

Herstory. (2019, September 7). https://blacklivesmatter.com/herstory/

History NOW. (2017, June 14). Ice Bucket Challenge clicktivism is leading to a real cure for ALS [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/U9Ne88gIXME

Latitude33. (2015, October 6). Social entrepreneuriship – Start a business, save the world, create wealth and sustainable profits [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/8NNyYej0UJg

Morozov, E. (2009). The brave new world of slacktivism [Blog post]. FP. https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/05/19/the-brave-new-world-of-slacktivism/

Move to End Violence. (2016, September 15). Ally or co-conspirator?: What it means to act #InSolidarity. https://movetoendviolence.org/blog/ally-co-conspirator-means-act-insolidarity/

Nagle, R. (2019, January 10). The Indigenous teen who confronted Trudeau about unsafe water took on the UN. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/8xwvx3/the-indigenous-teen-who-confronted-trudeau-about-unsafe-water-took-on-the-un

Naware, R. (2018, May 8). Environmental and indigenous rights activist to receive WWF’s top youth conservation award. WWF. https://wwf.panda.org/?327434

Noonan, D. (2018, June 8). The 25% revolution—How big does a minority have to be to reshape society? Scientific American. www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-25-revolution-how-big-does-a-minority-have-to-be-to-reshape-society/

Peace House. (2016, May 4). All Lives Matter [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/NtAAeyswlHM

Richmond, T. (2013). Duval public schools: No more KKK high school. Change.org. https://www.change.org/p/duval-public-schools-no-more-kkk-high-school

SAIH Norway. (2013, November 8). Let’s save Africa! – Gone wrong [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/xbqA6o8_WC0

Seeker. (2013, November 15). Your ‘like’ doesn’t help charities, it’s just slacktivism [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/efVFiLigmbc

Sirolli, E. (2012, September). Want to help someone? Shut up and listen! [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/ernesto_sirolli_want_to_help_someone_shut_up_and_listen?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Smoot, K. (2020, June 29). White people say they want to be an ally to black people. But are they ready for sacrifice? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/29/white-people-ally-black-people-sacrifice

TED. (2015, February 2). How the Internet has made social change easy to organize, hard to win [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Mo2Ai7ESNL8

TEDx Talks. (2020, December 7). Can one person change the world? | Kofi Hope | TEDxToronto [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/F9VzYWMGA6o

The Feed SBS. (2013, November 18). Clicktivism is bad for charity [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/mUiF6uTjMWI

10 ways youth can engage in activism. (n.d.). Anti-Defamation League. www.adl.org/education/resources/tools-and-strategies/10-ways-youth-can-engage-in-activism

The Center for Artistic Activism. (2018, April 9). Why artistic activism? https://c4aa.org/2018/04/why-artistic-activism

The Feed SBS. (2013, November 18). Clicktivism is bad for charity [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/mUiF6uTjMWI

Time. (2018, January 25). Patrisse Cullors on the history of the Black Lives Matter Movement and its political future [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/nwFq_MnaGds

TVO Docs. (2010, January 21). Social media: Online activism [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AN-kIJI_5wg

Unigwe, C. (2019, October 5). It’s not just Greta Thunberg: why are ignoring the developing world’s inspiring activists? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/oct/05/greta-thunberg-developing-world-activists

Varagur, K. (2019, September 30). Meet India’s teen climate advocate: Ridhima Pandey. The Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2019/0930/Meet-India-s-teen-climate-advocate-Ridhima-Pandey

Virtue signalling. (2020). In Oxford Learners Dictionaries. (2020). Retrieved October 21, 2020, from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/virtue-signalling

White, M. (2010). Clicktivism is ruining leftist activism: Reducing activism to online petitions. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/aug/12/clicktivism-ruining-leftist-activism

Why this photo of a politician with Malala is being criticized. (2019, July 5). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48794502

Wong, K. (2019, October 1). How to be a more conscious consumer, even if you’re on a budget. The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2019/10/01/smarter-living/sustainabile-shopping-conscious-consumer.html

Social Action for Social Change

Paula Anderton and Sabrina Malik