Globalization: A History

In our lifetime and in our parents and grandparents’ lifetime, there have been three waves of globalization (Rumford, 2008).

The first wave can be traced back to the 1870s. That lasted until the First World War. Industrialization was well underway at that time, and advances in transportation meant less trade barriers and more globalization of trade (Hill, 2012). Prosperity in some parts of the world led to the migration of more and more people. During this period, nearly 10% of the world’s population migrated to new territories (Maddison, 2007).

The first wave of globalization has a legacy in colonization. Many of the trade measures that are in place today can be traced back to the colonial structures of that time, when groups in power wanted to ensure they would always benefit and maintain their superiority.

For three decades starting in 1920, most economies faced major crises, and globalization slowed down (Lewis & Moore, 2009). But before long, the world entered the second wave of globalization (1950–1980). During this time, many economies picked up where they left off and grew at a rapid pace. New trade agreements and cartels like OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) were formed during that time period to encourage a global economy (Wallerstein, 2008).

The third wave of globalization started in the early 1980s. Advances in communication technologies made this stage evolve quickly. Many countries could not resist global trade associations such as the World Trade Organization and opened up their economies for global business (Stiglitz & Pike, 2004).

When we think about globalization, a new sense of community and locality comes to mind, where the world is interconnected and unified. But four decades later, critics are warning that the third wave of globalization has exploited the working class, caused more harm than benefit for developing economies, and ultimately made the rich richer and the poor poorer (Kunnanatt, 2013; Klein, 2007).

An important question many people are asking is if globalization in its current form (third wave) is the only feasible option for us right now.

Those who answer yes likely believe in “globalization from above.” Also called corporate globalization, “globalization from above” is driven by big business. It mainly serves the interests of transnational corporations and monetary institutions like the World Bank that work in collaboration with the most powerful economies in the world (Demaine, 2002). These corporations and institutions have made a lot of money off third-wave globalization and want it to continue.

But there are also those who believe in “globalization from below.” These include social movements, non-government organizations, and people who are active in grassroots initiatives and community-based movements. These people want to open up spaces for community building and meaningful participation in democracies.

Critics have pointed out that third-wave globalization has led to greater social exclusion and marginalization (Santos, 1998). Those who believe in “globalization from below” counter this through bottom-up approaches that represent the interests of ordinary people. For example, by participating in initiatives that “[re-inject] ideas of social justice, human rights and environmental sustainability into the global agenda” (Ife, 1995, p. 5). These movements resist “globalization from above” and offer meaningful alternatives to the models imposed by economic powerhouses and governments that keep the hegemony of the “haves” over the “have-nots” alive and well (Falk, 2013; Smith, 2008).

Citta`Slow

One example of a “globalization from below” response to “globalization from above” is the Slow Movement. This began with the “Slow Food” philosophy in Italy, which was a reaction to the extensive spread of “fast food” (Miele, 2008). It promoted eating local and sustainably grown food, and slowing down to cook and enjoy meals with friends and family. This expanded to become an overall philosophy of slow living.

Citta`Slow, which means “slow city,” is an international network of small towns that have been inspired by the Slow Movement. Now more than 100 countries worldwide are part of Citta`Slow and practicing in the slow-living movement as a measured response to globalization. Slow living has been called a form of “ethical cosmopolitanism” (Parkins & Craig, 2006). In Canada, four towns in British Columbia, Quebec, and Nova Scotia are part of the Citta`Slow movement (Cowichan Bay, Lac-Mégantic, Naramata, Wolfville).

Mullah Nasreddin, a Persian sage who used humour to share his wisdom, was asked to show the centre of the universe. He pointed to the hook on the ground where his donkey was tied. “There,” he said, “there is the centre of the universe—and if you don’t believe me, go and measure the equidistance from it around the world.”

Consider these questions:

- Is it possible for globalization to create one centre for the whole world?

- Can we have a form of globalization that allows for multiple centres?

Go Deeper

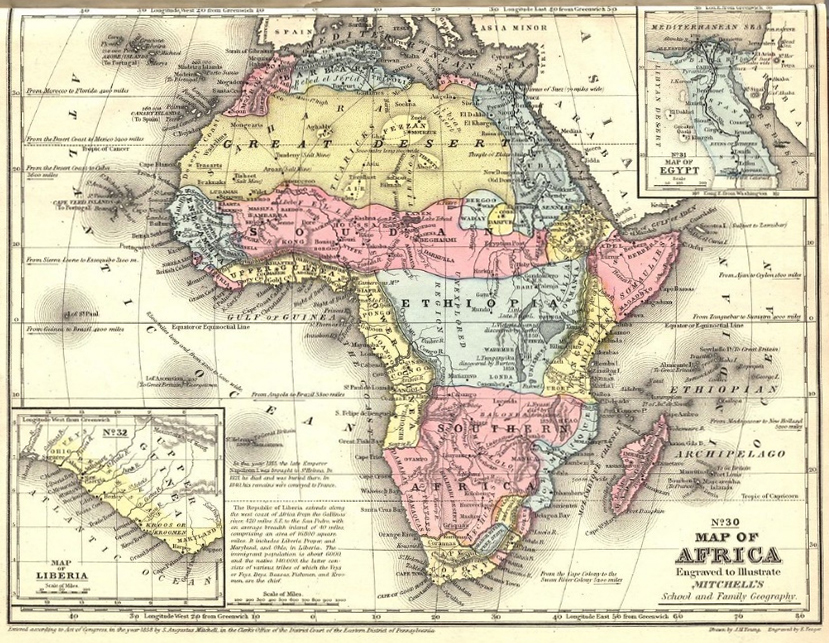

The Scramble for Africa refers to a time known as the New Imperialism period between the 1880s and the start of the First World War. European nations had long exploited African countries. They did this in the name of bringing civilization to Africa. But in reality, European countries were reaping the benefits of Africa by exploiting the land and its inhabitants. During this period, European countries divided Africa up between themselves and even created artificial states without taking into consideration cultural, religious, linguistic, or ethnic issues. In the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, France, and Germany tried to regulate European colonization and trade in Africa. But it was a failure. The involved nations did not agree on how to divide up Africa among themselves. One of the central reasons behind WWI is believed to be the dispute over who got what in Africa (Joplin, 2019).

Watch The New Scramble for Africa to get an idea of how the continent of Africa was taken advantage of and exploited by European powers. (Source: Al Jazeera English, 2014)