Converse

To converse with a source, you first need to “listen” to what it has to say. After that, it’s time to “respond.”

What You’ll Learn:

- How to listen to your source

- How to formulate a response

Partial Understanding

Full Understanding

In the above example, we see that jumping to a conclusion can often lead to a mistaken impression. It’s safer to have a complete understanding before we react. In this topic, we’ll highlight the importance of listening, or understanding, before responding.

Listening

Exercise A: Reading to Understand

Take a look at the following three claims and determine whether or not the author made them. If Manjoo made the claim, answer “true.” If Manjoo didn’t, answer “false.”

On July 10, 2019, The New York Times opinion columnist Farhad Manjoo wrote an article called “It’s Time for ‘They.’” Its main argument? “The singular ‘they’ is inclusive and flexible, and it breaks the stifling prison of gender expectations. Let’s all use it.”

Read the source.

1. According to Manjoo, the world would be slightly better off if we abandoned unnecessary gender signifiers as a matter of routine communication.

2. According to Manjoo, we should use “they” more freely, because language should not default to the gender binary.

3. According to Manjoo, gender is a ubiquitous prison for the mind, reinforced everywhere, by everyone, and only rarely questioned.

Responding

Exercise B: Reading to Respond

Using the same three claims from the previous activity, you’ll again determine whether or not they are “true” or “false.” Only this time, you’ll be answering “true” if you agree with the claim and “false” if you don’t (notice the missing prepositional phrase at the beginning of each sentence!). Hint: There is no right or wrong answer.

1. The world would be slightly better off if we abandoned unnecessary gender signifiers as a matter of routine communication.

2. We should use “they” more freely, because language should not default to the gender binary.

3. Gender is a ubiquitous prison for the mind, reinforced everywhere, by everyone, and only rarely questioned.

Without the prepositional phrase “According to Manjoo,” you take the fairly big step from listening to responding. In doing so, the answers are not as obvious as when you completed the exercise the first time, are they? That’s because you’re not just showing your understanding of the material. Now, you’re in the early stages of responding.

Tip

When determining whether or not an author’s claim is true or false, or whether or not you agree or disagree with it, consider asking yourself some key questions:

- Do the main ideas of the article match my experience or prior learning on this topic?

- Does the author use convincing evidence to support their ideas?

- Do the author’s ideas seem rational or justified?

- Has the author confronted or ignored ideas contradictory to their own?

- Is the article well-structured, i.e. are the ideas within it logically connected?

Comments, or Letters to the Editor

Nowhere is the process of listening and responding better displayed than in the comments section of an online article or letters to the editor in newspapers and magazines. Here, readers like you are given an opportunity to respectfully respond to an author’s argument (once you’ve listened to it, of course).

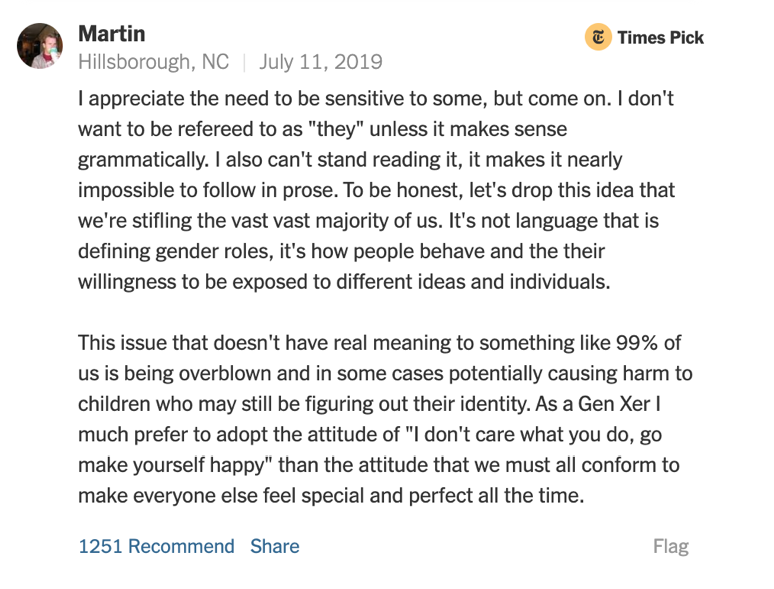

Take a look at the following conversation between the author, Farhad Manjoo, and one of their readers:

Here, you can see a conversation between reader and writer based on a difference of opinion. Maybe you too have differences of opinion with the author (see Exercise B: Reading to Respond). Or maybe you agree. Either way, determining what you believe in relation to an author’s claims is what it means to respond to a source.

Tip

Typically when you respond to a source, it’s unlikely that the author will be able to answer back, as Farhad Manjoo does in the above example. But that doesn’t mean you can’t anticipate what they would say. In fact, anticipating what an author would say in response to you is an effective method of argumentation. It can also encourage you to make your points as clearly and considerately as possible.

Tip

Before writing, consider including the following structural details in your comment:

An introductory statement or topic sentence that clearly expresses the main point(s) of your comment, i.e. What specific point or points are you trying to get across?

Supporting details so that your main point(s) makes logical sense, not just to you, but to your reader.

A concluding statement, where you try to make a lasting impact on your reader.

Try It!

Try writing your own comment!

In the box below, try writing out your own comment or letter to Farhad Manjoo’s article “It’s Time for ‘They.’” You can draw on relevant skills and strategies covered in Build Your Toolkit.

| TECHNIQUE | SUMMARY |

|---|---|

| Listen | First, actively read the source so that you can “hear” what the author is claiming. |

| Respond | Then, examine the claims themselves so that you can have your own “say.” |

See related subtopics in Absorb and Build Your Toolkit.

Gavin, F., Donville, E., Vavrusa, D., & Buchanan, D. (Eds.) (2010). Effective reading and writing for COMM 170 and beyond. Toronto: Pearson Education.

Letter to the editor. (2020). Teaching the Times. https://sites.google.com/site/teachingthetimes/short-assignments/letter-to-the-editor

Manjoo, F. (2019, July 10). It’s time for ‘they.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/pronoun-they-gender.html

Verify

“Everyone is entitled to [their] own opinion, but not [their] own facts.”—Daniel Patrick Moynihan

What You’ll Learn:

- How to verify the reliability of a source

- How to verify evidence to gauge credibility and accuracy

- How to examine a source for conflict of interest

As you probably know, the internet is filled with both information and disinformation. In this topic, we’ll discuss ways to distinguish between them.

Verifying the Reliability of a Source

Today, we mostly access information through various websites. So, what can we do to ensure that the information on these websites is reliable? The best place to start is with the website itself, or the source.

If you’re a postsecondary student, you’re fortunate to have privileged access to your college’s library, whose online databases contain hundreds of thousands of articles from sources that you can trust. That’s because they’ve been carefully selected by the librarians at your institution. In addition, your course instructors have likely included their own list of reliable sources for you to read and respond to.

The spread of disinformation became so impactful during the 2016 American election that it prompted Mark Zuckerberg to write an editorial in The Washington Post. In it, he urged his government to establish stricter online rules to protect elections.

Read the source.

Nevertheless, at some point during your studies, you’ll likely use online search engines to find supplementary articles on a given topic for the purposes of research and inspiration.

When verifying a source’s reliability, consider the three criteria discussed in Michael A. Caulfield’s 2017 book Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, which he bases on Wikipedia’s guidelines for reliable sources.

These three criteria are:

- Process

- Expertise

- Aim

Read more about them here.

Verifying Evidence to Gauge Credibility and Accuracy

Michael A. Caulfield’s book Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers (2017) discusses “four moves” that students can make “when confronted with a claim that may not be 100% true” (Chapter 2, para. 1).

Read about them here.

For the following example, let’s focus on the first of Caulfield’s “moves,” which is to “go upstream to the source” (Chapter 2, para. 3). Many of the articles we read online consist of an author’s faithful—we hope—reporting on their sources. If you’re ever in doubt of an article’s credibility and accuracy, try to track down the original source and check. Let’s try it!

Tip

Nowadays, most articles include hyperlinks directing us to an article’s original source. This makes it fairly easy for us to verify the evidence. It also demonstrates the author’s and source’s commitment to transparency. However, if the hyperlink doesn’t allow us to verify the evidence—for example, if the link is dead—then we should call into question its credibility and accuracy.

In October 2014, David Suzuki published the article “Commissioner’s Report Shows Canada Must Do More for the Environment.” In it, Suzuki highlights the major findings of a report by then Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Julie Gelfand. His conclusion? Canada must do more for the environment.

Read the source.

Because the commissioner’s report is hyperlinked in Suzuki’s article, we can easily verify his summary and conclusion. Let’s take a look.

View the report here.

| SUZUKI (2014) | COMMISSIONER’S REPORT (2014) |

|---|---|

| “Canada is not on track to meet its greenhouse gas emissions targets” (para. 4). | “[T]imelines for putting measures in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have not been met” (Chapter 1, para. 13). |

| “[Canada] . . . has delayed monitoring of oil sands pollutants” (para. 4). | “Most [oil sands] projects we examined are being implemented according to schedule” (Chapter 2, para. 37). |

| “[Canada] . . . has no clear guidelines regarding what projects require environmental assessments” (para. 4). | “Overall, we found that the Agency’s rationale for identification of projects for environmental assessment is unclear, specifically in making its recommendations to designate projects that may require an assessment” (Chapter 4, para. 20). |

In red, we see a discrepancy between Suzuki’s summary of the report and the report itself. Although the majority of Suzuki’s article is faithful to the report, this one discrepancy can impact its overall credibility and accuracy. As a result, Suzuki’s conclusion that “Canada must do more” is compromised. Of course, we would never have known this if we hadn’t made the extra move of “go[ing] upstream to the source” (Caulfield, 2017, Chapter 2, para. 3).

Examining a Source for Conflict of Interest

Up to this point, we have looked at ways to

- verify the reliability of the source; and

- verify evidence to gauge credibility and accuracy.

Similar to verifying reliability of your source is examining it for the possibility of a conflict of interest. Take a look at the following excerpt from the “Conflict of Interest” section in the CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices:

CBC’s journalists are, first and foremost, expected to be independent and impartial. This means that our primary allegiance is to the public. Any conflict, real or perceived, between that allegiance and our personal or professional interests risks corroding the trust placed in us by Canadians.

This means we strive to avoid actions that create an impression of partisanship or of advocacy for a cause. It means we consider carefully what organizations we associate with. It means that we are mindful of our public statements. And it means we recognize that our personal and business relationships have the potential to affect the perception of our work.

To guide our actions, we refer to the code of conduct and the corporate policies on conflict of interest and on political activity, and comply with their requirements.

Dealing with any real or perceived conflicts of interest requires transparency. We have a duty to disclose such situations to our supervisor and to strive to resolve any problems that may arise from them. (CBC, n.d.)

As Canada’s public broadcaster, we should hope that the CBC lives up to these standards and practices when it comes to conflict of interest. Either way, such noble aims are useful to keep in mind when looking at other sources. Ask yourself:

- Does the source’s publisher also have a mission statement on maintaining journalistic integrity and avoiding conflict of interest?

- Do they also encourage their journalists to be “independent and impartial”?

- Do they put a similar emphasis on transparency when there is a “real or perceived conflict of interest”?

If the answer is “no” to any or all of the above questions, then it’s probably wise to be suspicious of the information you find in that source.

Tip

Look out for conflict of interest. For decades, tobacco companies claimed that smoking was not unhealthy. They supported their position with scientific tests to prove they were right, but tobacco companies were funding the tests, thus controlling the conclusions. Years later, objective research conducted by scientists independent of the tobacco companies proved the opposite—that smoking is a serious health hazard. This classic example of a conflict of interest is dramatized in the 2005 movie Thank You for Smoking.

You can read about the movie here.

Try It!

While thinking about the three criteria for verifying a source’s reliability—process, expertise, and aim—rank the following websites in order from “most” to “least” reliable. This is based on your opinion; there is no right or wrong answer. Share your list with your class and see if it differs from your peers.

| PRACTICE | SUMMARY |

|---|---|

| Verifying the reliability of a source | Consider the three criteria discussed in Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers: process, expertise, and aim. |

| Verifying evidence to gauge credibility and accuracy | Consider the four “moves” discussed in Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers: 1) “Check for previous work”; 2) “Go upstream to the source”; 3) “Read laterally”; and 4) “Circle back” (Caulfield, 2017, Chapter 2, para. 3). |

| Examining a source for conflict of interest | Consider the CBC’s “Conflict of Interest” policy in order to see if your sources measure up to their standards. |

See related subtopics in Connect, Build Your Toolkit, and Absorb.

Caulfield, M. A. (2017, January 8). Web literacy for student fact-checkers. Pressbooks. https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/

CBC. (n.d.). Journalistic standards and practices. https://cbc.radio-canada.ca/en/vision/governance/journalistic-standards-and-practices

Gavin, F., Donville, E., Vavrusa, D., & Buchanan, D. (Eds.) (2010). Effective reading and writing for COMM 170 and beyond. Toronto: Pearson Education.

Suzuki, D. (2014, October 14). Commissioner’s report shows Canada must do more for the environment. The Georgia Straight. https://www.straight.com/news/749141/david-suzuki-commissioners-report-shows-canada-must-do-more-environment

Zuckerberg, M. (2019, March 30). The internet needs new rules. Let’s start in these four areas. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mark-zuckerberg-the-internet-needs-new-rules-lets-start-in-these-four-areas/2019/03/29/9e6f0504-521a-11e9-a3f7-78b7525a8d5f_story.html

Recognize Logical Fallacies

A logical fallacy is “a failure in reasoning which renders an argument invalid” (“Fallacy,” n.d.).

What You’ll Learn:

- How logical fallacies work

- How to avoid logical fallacies in your own writing

Does the following conversation between roommates look familiar to you?

Roommate 1: You were on dish duty yesterday. Why’s the sink still full of dirty dishes?

Roommate 2: Relax. This is an apartment, not a laboratory.

Roommate 2’s response is a classic example of the “straw man” fallacy, in which a person’s point is intentionally misrepresented, making it easier to defeat (“Straw man,” n.d.).

In this case, it’s easy for Roommate 2 to defeat the idea that a student apartment should conform to the same standards of cleanliness as a laboratory. Who would insist on that? Of course, Roommate 1 never said anything of the sort. All she asked was “Why’s the sink still full of dirty dishes?” and pointed out it was Roommate 2’s turn to clean them.

Logical fallacies are as widespread in daily life as they are in writing. Understanding how they work is the best method of protection against their faulty logic.

How Logical Fallacies Work

There are plenty of online resources that classify logical fallacies by name, definition, and example. The Purdue University Online Writing Lab, a web resource for English students and instructors, is an excellent place to start.

You can access its page on logical fallacies here.

Let’s examine a few from the list while keeping the following two questions in mind:

- Why is the fallacy effective at first?

- Why is the same fallacy ineffective on closer inspection?

In June Callwood’s 2007 essay “Forgiveness Story,” published in the Canadian magazine The Walrus, she disapproves of sympathizing with abusers if they—the abusers—were also victims of past abuse. Or, in Callwood’s words, she disapproves of the idea that “bad parenting comes from being badly parented” (para. 11).

The reason for Callwood’s disapproval? “This technique can be applied to almost any injustice and falls within the rapists-were-beaten-as-children, poor them school of thought, which for some sceptics veers perilously close to non-accountability” (para. 13).

Read the source.

You may find her argument to be valid and compelling. It’s reasonable to conclude that Callwood has made a strong point (her graphic language, coloured by sarcasm, may add to its strength). After all, shouldn’t abusers be held accountable for their actions and not be excused of them due to the hardships they have faced in their own lives?

However, consider that within criminology and social theory, many books have been written and studies conducted on the cyclical nature of abuse, with conclusions presenting different insights than Callwood’s.

If you believe an argument oversimplifies matters, it may be an example of a fallacy known as “hasty generalization” or “straw man.” Do you believe Callwood’s article to be accurate or overgeneralized? Is it…

You decide.

“This technique can be applied to almost any injustice and falls within the rapists-were-beaten-as-children, poor them school of thought, which for some sceptics veers perilously close to non-accountability.”

In the same essay, Callwood describes our day and age—the 21st century—as one in which we no longer have the ability to forgive. Why? According to Callwood, we do not understand the religious teachings on forgiveness as well as we used to.

This, then, is how Callwood describes the 21st century:

[T]his is the age of anger, the polar opposite of forgiveness. Merciless ethnic, tribal, and religious conflicts dominate every corner of the planet, and in North America individuals live with high levels of wrath that explode as domestic brutality, road rage, vile epithets, and acts of random slaughter. (para. 4)

Again, many may find Callwood’s claim to be well-taken (notice again the effectively graphic quality of her language: “merciless,” “dominate,” “explode”). If we’ve just watched or read the news, we may find ourselves nodding in agreement with her harsh indictment of our century.

Other readers may question whether past centuries weren’t just as plagued—if not more so —by “merciless ethnic, tribal, and religious conflict” (para. 4). Yet people in those times, according to the argument, would have had a better understanding of the religious teachings on forgiveness than ours does.

If you judge that the argument is flawed, it may be an example of “post hoc ergo propter hoc” or, once again, “hasty generalization.” Do you believe this claim is…

You decide.

“[T]his is the age of anger, the polar opposite of forgiveness. Merciless ethnic, tribal, and religious conflicts dominate every corner of the planet, and in North America individuals live with high levels of wrath that explode as domestic brutality, road rage, vile epithets, and acts of random slaughter.”

For our final example, let’s look at the central question at the heart of Callwood’s essay: to forgive or not to forgive? She clearly answers “forgive” because of the benefits forgiveness can have on our health, both mental and physical.

The way that Callwood presents it, there are two outcomes attached to either choice:

The choice may seem simple. If given the choice between having “scalding thoughts of revenge” or “peace of mind” (para. 18), what would you choose? Most of us would have to agree with the author’s choice here.

Yet some may feel that “scalding thoughts of revenge” and “peace of mind” are but two extreme poles on a spectrum. Between them lie a host of other outcomes, each less extreme in degree than the two poles.

If that’s your judgment, you may feel that you’re looking at an example of a fallacy known “either/or.” With that in mind, do you feel that the argument is…

You decide.

Not to forgive – To forgive

“scalding thoughts of revenge” – “peace of mind”

Avoiding Logical Fallacies in Your Own Writing

It’s important to be on the lookout for fallacies in the world of arguments and opinions. This applies to your dual roles as reader and writer.

If you agree that logical fallacies can be effective at first, but not as much on closer inspection, then you will probably want to avoid using them in your own writing.

Tip

Because logical fallacies often appear early in the writing process, as in the rough draft, consider using strategies covered in Practice Iterative Design and Peer Review for the purposes of checking your work for logical fallacies

Try It!

Using this list of logical fallacies, try to determine the fallacy in the following example:

The author’s essay is poorly executed because they are a bad writer with a very limited understanding of their subject matter.

We covered logical fallacies—how they work and how to avoid them in our own writing. Continue to keep logical fallacies in mind by:

Learning about the different types (their names, definitions, and examples)

Recognizing specific instances when other writers use them

Understanding their superficial effect (if closely examined, they’re rendered invalid)

Watching out for them in your own writing as you move through the writing process

See related subtopics in Build Your Toolkit and Share Your Work.

Callwood, J. (2007, Jun 12). Forgiveness story. The Walrus. https://thewalrus.ca/forgiveness-story/

Fallacy. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/fallacy

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). Logical fallacies. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/logic_in_argumentative_writing/fallacies.html

Straw man. (n.d.). In Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/definition/straw_man

Challenge Assumptions

An assumption is the “taking of anything for granted as the basis for argument or action” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.).

What You’ll Learn:

- How to challenge the assumptions in a writer’s claim

- Some strategies for challenging our own assumptions

Does the following conversation between acquaintances look familiar to you?

Acquaintance 1: You would love this movie. I just know it.

Acquaintance 2: Ok, thanks. I’ll check it out.

Two hours later…

Acquaintance 2 (thinking): What a waste of time. I’ll never get those two hours back.

This could’ve been avoided if Acquaintance 1 had not taken for granted Acquaintance 2’s taste in movies—in other words, if they’d challenged their own assumption. Doing so might’ve saved Acquaintance 2—not a science fiction fan—the two hours she spent watching Flaming Globes of Sigmund.

Try not to let this happen to you! If you’ve taken anything for granted en route to an argument, action, or claim,

- stop;

- retrace your steps; and

- challenge your underlying assumption.

Challenging the Assumption in a Writer’s Claim

On June 12, 2005, the late Steve Jobs delivered a commencement address at Stanford University. Its main message? “You’ve got to find what you love” (para. 15).

Read/view the source.

In Jobs’s speech, he preaches self-reliance. This is illustrated by his decision to drop out of college. Jobs’s faith in himself was so strong that he believed he could achieve his goals without institutional support. And he did! Jobs encourages his audience of recent graduates to have the same reliance and faith in themselves:

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary. (para. 23)

In “‘Just Three Stories’: The Career Lessons Behind Steve Jobs’ Stanford University Commencement Address,” authors Julia Richardson and Michael B. Arthur (2013) challenge the following assumption in Jobs’s message of self-reliance: “Whereas Jobs was in a situation where he could drop in and out of classes and presumably had parental support to do so, others may not be quite as fortunate due to their social and economic circumstances” (para. 25).

In other words, it was Jobs’s good fortune that enabled him to rely on himself, and in preaching his message of self-reliance to others, he assumes that they are as fortunate as he was. As a result, Jobs may be taking for granted the idea that “in all careers there are constraints on which opportunities can be accessed” (King et al., 2011, as cited in Richardson, Arthur, 2013, para. 25).

Jobs’s first story, on “connecting the dots,” is about gaining the rewards of patience. After dropping out of college in just six months, Jobs stayed on campus for another 18 months as a “drop-in.” During this time, he “dropped in” on classes, like the one on calligraphy that would later influence Apple’s “beautiful typography.” About this period of his life, Jobs says the following: “And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on” (para. 6).

Richardson and Arthur (2013) challenge another assumption in Jobs’s advice here. According to them:

Although Jobs was able to spend time searching for his calling, for some—if not most—people, responsibilities to others and social and economic circumstances do not allow them to search for their calling, let alone fulfill it (see Berg, Grant & Johnson, 2010). Similarly, as Jobs himself acknowledged, he found his calling early in life whereas others may not. (para. 26)

By encouraging his audience of recent graduates to patiently follow their curiosity and intuition, Jobs is assuming they have the same amount of time and freedom from responsibilities as he did. As a result, he may be taking for granted his audience’s diverse “social and economic circumstances.”

In Jobs’s second story, about “love and loss,” he says “that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life” (para. 13).

Not only did getting fired lead Jobs to fall in love with his future wife, but it also led him to start two successful companies before his triumphant return to Apple. Based on this experience, he urges his audience not to lose faith in themselves during difficult times.

Richardson and Arthur (2013) challenge an assumption in this part of Jobs’s speech as well:

Regarding the proclaimed positive side of involuntary job loss, it should be acknowledged that Jobs was in a very different situation than most people who lose their job. Indeed, recent research has suggested that most people are likely to experience lower self-esteem, depression, and health problems after losing their job (Zeitz et al., 2009). (para. 27).

The authors then paraphrase the following conclusion: “[W]hereas Jobs welcomed his newfound freedom to explore and craft further career opportunities, for many people the change and uncertainty incurred during job loss is more likely to be a source of stress than liberation (Halbesleben & Buckley, 2004)” (para. 27).

By encouraging his audience of recent graduates to embrace the times when, as he puts it, “life hits you in the head with a brick” (para. 15), Jobs is assuming that they will be able to rebound as successfully as he did. As a result, he may be taking for granted that other people will find opportunity in a job loss, too.

Some Strategies for Challenging Our Own Assumptions

Steve Jobs was an incredibly successful person in his lifetime. But, as we learned in the previous section, not even he could avoid making assumptions. That’s because we all make them. No matter who we are or what we’ve accomplished, assumptions are a part of life. So, let’s take a look at some strategies for challenging our own assumptions.

1. Practise the Assumption-Challenging Habit

An effective method of grammar instruction is based on correction. For example, to learn to avoid run-on sentences in your own writing, you may find it effective to correct run-on sentences in someone else’s. This same method can be used for assumptions. The more we practise challenging assumptions in someone else’s writing, the better we’ll become at challenging those that may appear in our own.

As was demonstrated by Julia Richardson and Michael B. Arthur’s commentary on Steve Jobs’s commencement speech, challenging assumptions means figuring out what the author might have taken for granted en route to a claim.

2. Practise Iterative Design and Peer Review

If Steve Jobs had given a draft of his speech to Richardson and Arthur for advanced feedback, they could’ve flagged his assumptions listed above. At that point, Jobs might’ve gone back and revised his points.

Assumptions are like blind spots in our own thinking. Which is why we need others—friends, family members, teachers, and peers—to help us see what we might be taking for granted. Therefore, review the material covered in Practice Iterative Design and Peer Review. With the help of others, we can challenge our own assumptions.

Tip

Assumptions are tricky because they can often be correct. For example, a college professor assigns her automotive students a reading about the history of cars because she assumes they will like it, given their program of study. The first time, her assumption is correct. The second time, however, she discovers what she’d taken for granted: not all automotive students are interested in cars as a historical subject. Now, before assigning this reading again, she polls her class first.

3. Practise Asking before Assuming

Here’s an alternate version of the conversation we looked at earlier.

Acquaintance 1: Do you like science fiction movies?

Acquaintance 2: No. That’s my least favourite movie genre.

Acquaintance 1: Good to know! I’ll remember that before my next movie recommendation.

Similarly, in the example of the college professor and her automotive students, she asks them about their interest in the history of cars first, before assigning that particular reading. As for Steve Jobs, if he’d done some research on the effects of involuntary job loss first, maybe he wouldn’t have put such a positive spin on getting fired.

An assumption is like jumping to a conclusion. Especially when it’s a big jump, you don’t want to take anything for granted. Instead, take all the necessary precautions first, which means ask yourself and others some key questions. If you do that, your jump—i.e. your conclusion, claim, argument, or action—might be a success!

Try It!

In the following claim, think about what the author might be taking for granted.

By assuming that all millennials are the same, is it possible that the author is taking for granted the sheer diversity of the millennial population

As Reniqua Allen (2019) points out in her TED Talk “The Story We Tell about Millennials—and Who We Leave Out,” “There are also extreme differences [among millennials], often between millennials of color and white millennials. In fact, all too often, it seems as though we’re virtually living in different worlds.”

Read/view the source.

Here are some key takeaways from our topic on challenging assumptions:

- An assumption is “the taking of anything for granted as the basis for argument or action” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.).

- Practise the assumption-challenging habit: challenge the assumption in a writer’s claim.

- Keep assumptions in mind when practising iterative design and peer review.

- Try asking before assuming.

See related subtopics in Build Your Toolkit and Share Your Work.

Allen, R. (2019). The story we tell about millennials—and who we leave out [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/reniqua_allen_the_story_we_tell_about_millennials_and_who_we_leave_out?language=en

Assumption. (n.d.). In Oxford English Dictionary. https://www-oed-com.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/view/Entry/12052?redirectedFrom=assumption#eid

Jobs, S. (2005, June 12). ‘You’ve got to find what you love,’ Jobs says. Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/14/jobs-061505/

Richardson, J., & Arthur, M. B. (2013). “Just three stories”: The career lessons behind Steve Jobs’ Stanford University commencement address. Journal of Business and Management, 19(1), 45–57. http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=https://search-proquest-com.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/docview/1549238166?accountid=39331

Understand Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is defined as “the tendency to seek or favour new information which supports one’s existing theories or beliefs, while avoiding or rejecting that which disrupts them” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2019).

What You’ll Learn:

- What confirmation bias is

- What confirmation bias looks like in action (or lessons for how to avoid it)

Do you like puzzles?

“A Quick Puzzle to Test Your Problem Solving” by David Leonhardt (2015) is based on an experiment conducted by Peter Cathcart Wason, who is credited with coining the phrase “confirmation bias.”

Try solving the puzzle yourself here. Make sure to take note of the following instruction: “You can test as many sequences as you want” (Leonhardt, 2015), but you only get one guess.

What Is Confirmation Bias?

If you’re like most people, when you tried to solve “A Quick Puzzle to Test Your Problem Solving” you probably entered sequences of numbers that obeyed the rule rather than disobeyed it. And maybe that led you to guess that “[e]ach number is double the previous number” (Leonhardt, 2015). A good guess! But incorrect. And possibly premature.

According to Leonhardt, entering a sequence of numbers that disobeyed the rule rather than obeyed it may have been the key to solving the puzzle. However, as the author states in their explanation, the majority of people “don’t want to hear the answer ‘no.’ In fact, it may not occur to them to ask a question that may yield a no […] It’s a lot more pleasant to hear ‘yes.’ That, in a nutshell, is why so many people struggle with this problem” (para. 3).

In other words, it’s a natural human tendency to seek information that confirms our beliefs (yes’s) rather than contradicts them (no’s). Or, as Leonhardt explains, “[n]ot only are people more likely to believe information that fits their pre-existing beliefs, but they’re also more likely to go looking for such information” (para. 6).

Confirmation Bias in Action (or Lessons for How to Avoid It)

Author David Leonhardt offers the following two examples of confirmation bias within the context of reading and writing:

If you’re politically liberal, maybe you’re thinking of the way that many conservatives ignore strong evidence of global warming and its consequences and instead glom onto weaker contrary evidence. Liberals are less likely to recall the many incorrect predictions over the decades, often strident and often from the left, that population growth would create widespread food shortages. It hasn’t. (para. 7)

Reading this, are you surprised that there is such a growing divide between liberal and conservative viewpoints today? Maybe one explanation for this is that each side is virtually ignoring the other.

Let’s take a detailed look at two other examples of possible confirmation bias in action. By doing so, hopefully we can learn some lessons for how to avoid it.

Example 1: Cellphones in School

If you already believe that cellphones should be kicked out of school, then this editorial, and many others just like it, will serve as confirmation of your belief. And if you only give your attention to articles like this one, you may be less open to hear the other side.

Now, let’s imagine you’ve come to this editorial as someone who does not believe that cellphones should be kicked out of schools.

Let’s take an issue we can all relate to: cellphones in the classroom. On October 25, 2017, an editorial was published in Bloomberg News called “Kick Mobile Phones Out of School”; in it, research was used to show that cellphones “[contribute] to sloppy work, reduced concentration and lower problem-solving capacity” (para. 2), among other adverse effects.

Read the source.

Looking Up is an award-winning blog by Andrew Campbell, an Ontario-based primary school teacher. In his blog post “We Need Cellphones in School Because They’re Distracting” (2017), Campbell, who opposes banning cellphones in the classroom, discusses the Bloomberg News editorial mentioned above.

Campbell doesn’t dispute the editorial’s claim that cellphones can be a distraction in school. In fact, he accepts it. What he disputes is the solution to this problem. “The ability to self-regulate the use of devices,” he claims, “is a critical skill if students are to become productive adults” (para. 10). He goes on to write the following:

This, not their role in learning, is the most important reason we need cell phones in [the] classroom. Students need to learn, from an early age, how to regulate their use of digital devices. Soon cell phones won’t be considered technology. They’ll be tools we use for certain jobs and then put away. But until then schools and teachers can play a vital role in teaching students how to use cell phones effectively and responsibly. (para. 11)

Andrew Campbell’s blog post is an excellent example of what we can do to avoid confirmation bias. Consider the following habits he demonstrates in his blog post:

- He took the time to read and understand the other side. Even though he remains opposed to the ban, reading and understanding the other side has enabled him to clarify and maybe even modify his own position on the issue.

- He found a point of agreement. Both he and the editorial agree that cellphones can be distracting for students, just as they can be distracting for drivers. Even though they disagree on a solution, finding other points of agreement can often lead to a constructive dialogue between opposing viewpoints.

Example 2: Climate Change

Maxime Bernier, the leader of the People’s Party of Canada, wrote a controversial tweet during the lead up to the 2019 Canadian federal election in which he disputed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s use of the word “pollution” to describe carbon dioxide, or CO2 (Trudeau had used the word while proposing his plans for a carbon tax).

“CO2 is NOT pollution,” Bernier (2019) tweeted. “It’s what comes out of your mouth when you breathe and what nourishes plants.”

You can read more about his controversial tweet here.

Bernier (2019) repeated his claim that “CO2 is NOT ‘pollution’” in a tweet appearing a few months later, which received 7.4 thousand likes. Here’s a brief sample of its favourable replies:

- “Thank you Max for speaking the truth” (Nelmes, 2019).

- “Bravo [. . .] I said it all along, CO2 is food for plant” (Phoenix, 2019).

- “Maxime Bernier, thank you, thank you, thank you for speaking TRUTH” (Shayne, 2019).

Whereas a carbon tax can and should be debated among people and politicians, the same can’t be said for the way that CO2 pollutes our planet. In fact, in 2007, the US Supreme Court ruled that CO2 is a pollutant. And it’s not alone in its judgment. Climate scientists and world leaders from around the globe agree.

Here, we may see confirmation bias in action, and a lesson for how to avoid it. Despite the unscientific nature of Bernier’s tweets, there were many who not only liked them but replied to them favourably. Why is that?

- Is it because their opposition to a carbon tax was so strong that they were inclined to agree with him, despite the absence of science in his tweets?

- By agreeing with him, is it also possible that they were avoiding or rejecting contradictory information, like the US Supreme Court’s 2007 ruling that CO2 is a pollutant?

If you answered “yes” to both questions, then you will probably agree that confirmation bias played a role in their decision to like and favourably reply to Bernier’s tweets.

Tip

Did you know that confirmation bias is just one form of bias? Familiarize yourself with these other forms of bias by looking up their definitions:

- Implicit bias

- Explicit bias

Try It!

As we learned from the puzzle activity at the beginning of this unit, “[w]hen you seek to disprove your idea, you sometimes end up proving it—and other times you save yourself from making a big mistake. But you need to start by being willing to hear no” (Leonhardt, 2015, para. 14).

With that in mind, sort the following two claims into their appropriate columns:

Now, go search for information online that contradicts your opinion. For example, if you “agree” that cellphones are harmful for students, seek information that claims the opposite. Similarly, if you “disagree” that climate change is primarily caused by humans, seek information that claims the opposite. Share your findings with your class.

Tip

One proven method to combat confirmation bias is to seek and be open to information that disproves or contradicts—rather than supports—your opinion.

Check the following boxes if you…

See related subtopics in Connect, Build Your Toolkit, and Absorb.

Bernier, M. [@MaximeBernier]. (2019, April 1). 1. CO2 is not ‘pollution’. 2. Increasing gas prices by four cents will have zero effect on climate. 3. You [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/MaximeBernier/status/1112677625619759105

Campbell, A. (2017, October 28). We need cellphones in school because they’re distracting [Blog post]. https://andrewscampbell.com/2017/10/28/we-need-cellphones-in-class-because-theyre-distracting/

Confirmation bias. (2019). In Oxford English Dictionary. https://www-oed-com.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/view/Entry/38852?redirectedFrom=confirmation+bias#eid1263597520

Joseph, R. (2018, October 25). Reality check: Maxime Bernier says CO2 isn’t a pollutant. Climate scientists say he’s wrong. https://globalnews.ca/news/4595603/reality-check-maxime-bernier-co2-pollution/

Kick mobile phones out of schools. (2017, October 25). https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2017-10-25/kick-mobile-phones-out-of-class

Leonhardt, D. (2015, July 2). A quick puzzle to test your problem solving. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/03/upshot/a-quick-puzzle-to-test-your-problem-solving.html?_r=0

Nelmes, B. [@billnelmes1]. (2019, April 1). Thank you Max for speaking the truth [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/billnelmes1/status/1112767432312020994

Phoenix. [@Forwhat71379442]. (2019, April 1). Bravo @ MaximeBernier I said it all along CO2 is food for plant [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Forwhat71379442/status/1112882882576506881

Shayne. [@shayne12877208]. (2019, April 1). Maxime Bernier – Thank you, thank you, thank you for speaking TRUTH [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/shayne12877208/status/1112726425994326016

Answering “true” for each claim shows that you understand—or have listened to—some of the main claims in the article “It’s Time for ‘They’” by Farhad Manjoo. Well done! Listening is the first step when conversing with a source. After all, before responding to someone’s claim, you first have to know what it is, right? Only then can you decide if you agree or disagree, and come up with your reasons why.