Focus on Process

Serve your readers through your investment in the writing process. Plan your time. Write iteratively, looping through the process several times.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why your process matters to your readers

- How the writing process works

- How to write iteratively

The writing process is a bit like hosting a dinner. There’s far more involved than just grabbing whatever’s in the fridge and serving it.

- The experience is social. You focus on someone else’s needs and preferences.

- You plan and organize early in the process, and perhaps do some research to offer the right thing.

- Once it’s underway, you have to see it through to the end.

- Along the way, you make little adjustments and improvements.

- The most important moment is when you present what you’ve made.

- You learn from the process—insights you can use the next time around.

- However small it may be, the experience reverberates outward. Connections form. Relationships shift.

- The experience is ultimately about people.

Why Process Matters to Your Readers

Be a Maker

When you write, you make something for others.

- Making is a process (exploring, researching, planning, drafting, revising, and so on).

- The others are your target readers.

Look at Process

A thoughtful, deliberate process improves the quality of the product, and therefore serves the reader.

Former Globe and Mail columnist Margaret Wente argues that postsecondary students in 2017 (the time of her writing) are overprotected and coddled by the expansion of student services for mental health and accessible learning. It leaves them unable to cope with the “real” world, she claims. Elamin Abdelmahmoud counters that Wente unfairly characterizes students and unjustly dismisses a growing mental health crisis on campus.

You’re writing a critique essay on Elamin Abdelmahmoud’s “I Sure As Hell Wouldn’t Want To Be a Student Now: An Open Letter to Margaret Wente.”

Consider how two stages in the writing process help you and your readers:

| STAGE | WHAT YOU ACCOMPLISH | HOW YOUR READER BENEFITS |

|---|---|---|

| Explore the Article | • Determine what will be of most interest to readers.

• Find the most significant moments in Abdelmahmoud’s article. • Discover what other people are saying about this issue. | • Strong inputs mean strong outputs. Your research and exploration enrich your argument for your reader. |

| Plan OR Reverse Outline Your Essay | • Decide your main points and the order to put them in. This can happen at the pre-drafting stage or after a complete draft, when you outline what you have as a way of seeing it clearly so you can develop it (“reverse outline”). | • Without organization, readers can’t make sense of things. Your planning or reverse outlining establishes the solid structure and organization that will help readers follow your ideas. |

The Writing Process Overview

Here we will take a top-level view of the writing process. In other topics, we’ll dive deeper into some of the details.

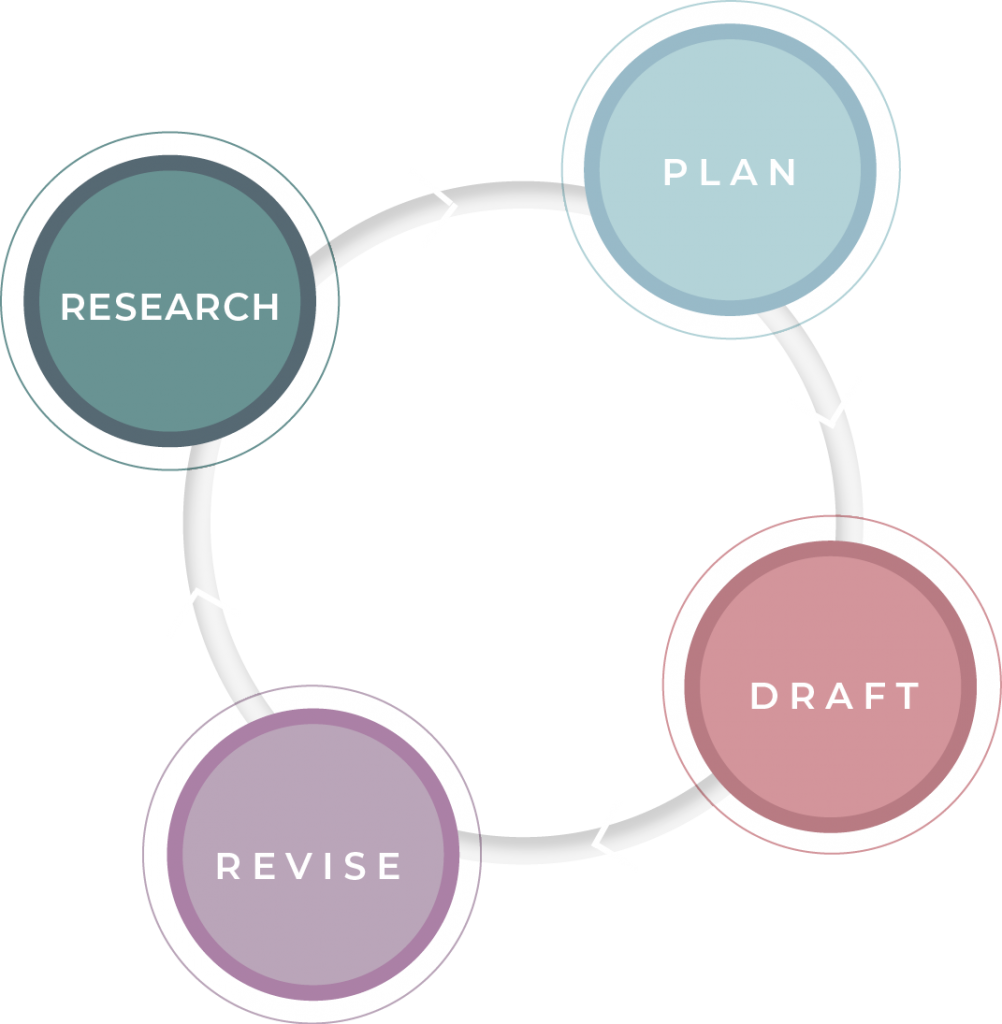

Fundamentally, the writing process is Research – Plan – Draft – Revise.

Adapting Process

There’s a logic to the eight-step writing-process sequence you’ve just learned.

But you can also reorder the steps, or leave some out.

- Draft

- Proofread

You can also adapt the process to suit your preferences:

- Draft

- Reverse-outline your draft and develop the structure

- Do research and exploration to enrich the draft before your first major rewrite

Alternatively:

- Plan and research

- Draft, rewriting, and revising as you go

This approach folds step 6 (revision) into step 4 (drafting). This method is generally not as efficient. But for some people, it just works.

Process is not a set of rules. Adapt as needed.

Iterative Process

More sophisticated projects—a critical essay, a technical report—often benefit from an iterative approach.

Iteration means “repeated process.” For example:

- Explore

- Plan

- Write draft 1

- Get feedback

- Explore new ideas

- Revise into draft 2

- Get more feedback

- Plan new section

- Revise into draft 3

- Proofread

You can repeat any steps, in whatever order, as many times as you need.

Often, writers need to finish a first full draft before they understand what they are trying to do.

The first draft (up to step 3 in the above example) is all about discovery. It is messier and more writer-focused than the final product will be.

For more information on the difference between writer-focused and reader-focused drafts, see Acts of Writing.

The steps of feedback, revision, and additional exploration and planning are about transforming that work into a reader-focused draft.

Try It!

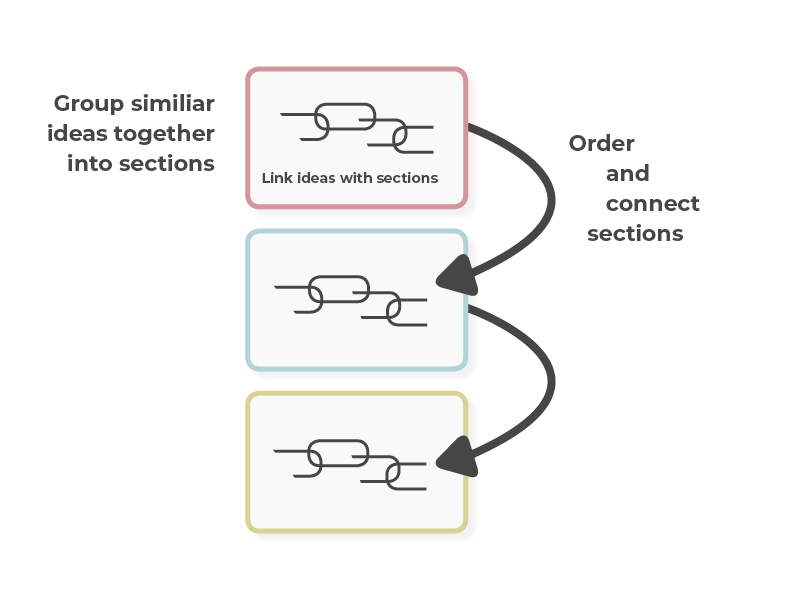

When you plan or reverse outline a project, you think about the structure and organization of the product. Structure is essential to readers being able to follow your ideas. This stage of the writing process has a huge impact on how readers respond to your argument and ideas.

A writer-focused draft comes early in the writing process. It’s the first full draft and is meant to help the writer get a sense of what they are trying to do. The reader-focused draft develops through the revision process. To create this draft, the writer thinks more consciously about what readers need and how they will respond.

Abdelmahmoud, E. (2017, September 22). I sure as hell wouldn’t want to be a student now: An open letter to Margaret Wente. Chatelaine. https://www.chatelaine.com/opinion/campus-mental-health/

Baron, M. (2015, March 2). Acts of Writing. https://actsofwriting.wordpress.com/2015/03/02/reader-based-vs-writer-based-prose/

Practise Iterative Design

Don’t just write. Design your communications by looping through the stages of prototyping, testing, and refining.

What You’ll Learn:

- What iterative design means

- How to design for the needs of readers

- How iterative design can improve your writing

Design means to plan and create something. Iterative design means to loop repeatedly through the design process, gradually refining the product through feedback.

Iterative design is common in the development of commercial and tech products:

| Pixel 3 Phone | Pixel 4 Phone | |

|---|---|---|

| Specifications (RAM) | 4GB RAM | 6GB RAM |

| Updated Features | Camera: Dual front cameras for wider view | Camera: New telephoto lens for better zooming |

| New Features | Titan M chip for more secure passwords and operating system | Motion Sense to control actions without touch |

Writers and their readers can benefit from this approach. Picture the following process:

- Draft something

- Get feedback

- Revise based on the feedback

- Get more feedback

- Revise based on that feedback

- Etc.

In the iterative design approach, you share a draft long before your project is finalized.

Get readers’ reactions to your work while you’re still developing it.

Iterative Design

Characteristics of iterative design:

- Focus on a user’s needs

- Prototype to meet those needs

- Test the prototype with users

- Refine and improve the design

Meet the Audience’s Needs: Connection First

Iterative design is all about connection. Focus on your audience’s needs, even when making an argument or disagreeing with someone.

This approach fits with any communication situation, including essay writing and public speaking.

In a debate, your opponents need several things:

- Evidence that you’ve heard and understood them, and that you are open to hearing their point of view

- Clear, direct communication of your claims and reasoning, so they in turn can understand and respond

- Accurate, credible evidence backing up your points

- Unbiased language

With that in mind, consider these critical responses to an argument made by Mark Kingwell.

In May 2020, Mark Kingwell wrote an op-ed in Canada’s Globe and Mail to argue that online education was inferior to face-to-face education (“Let’s Admit It—Online Education Is a Pale Shadow of the Real Thing”). Kingwell was responding to the rapid transition to online learning with the onset of COVID-19 that March.

Response 1

“Biased opinion coming from an institutionalized professor” (monexatb, 2020). Read the comments here.

Response 2

“Contributor Mark Kingwell may be right, but he may also just be resisting change” (Daudelin, 2020).

Read the letter here

The writer of this letter welcomes all readers, including those who share Kingwell’s view. Notice the qualifications:

- Acknowledgement of the other side (“Kingwell may be right”)

- Limitation of the argument (“he may also just be resisting change,” as opposed to something aggressive like “he’s clearly just resisting change”)

Response 3

“I teach legal studies at a community college. I recognize the necessity of online teaching to salvage the academic year. But I lament the loss of the classroom for two major reasons” (Berger, 2020).

Read the source.

The opening lines of this letter clearly establish the main point and provide a quick structural roadmap (“two major reasons”). The author also qualifies the argument and begins with context that personalizes the letter. It reaches out to readers by being clear, fair and personal.

Design your communications to meet the recipient’s needs.

How do you discover your target audience’s needs and expectations?

- When possible, just ask!

- Put yourself in a reader’s shoes.

- Analyze different readers’ likely expectations and motivations.

Prototype Rapidly

Step 1: Get it off the ground

A prototype is a rough draft. Its purpose is to generate feedback.

Think about a target reader’s needs, then produce the quickest draft that you think fits those needs.

“Quickest” depends on the size of the project. A research project usually involves a lot of reading, exploring, prewriting, and outlining before you’re even able to make a draft.

Consider showing someone your initial ideas in note or outline form. Or write the first full draft as early in the process as you can.

The point is, the first thing a reader sees doesn’t need to be polished or fully formed.

Parallel or sequential?

In technical design, prototyping may be either parallel or sequential.

- Parallel prototyping: You offer users several versions at once (Hohl, 2017).

- Sequential prototyping: You offer one version, apply the feedback, offer the next version, and so on.

In the world of writing, prototyping usually makes more sense.

But you could offer a reader different versions of one brief section of a document. For example, you could draft two separate introductions and say to your reader, “Here are two possible intros. Which works better?”

Step 2: Give it a once-over to correct the obvious errors or gaps

It’s better to get feedback on an imperfect version early on than to put off receiving feedback.

That said, aim to provide something as error-free as possible. Don’t trip readers up with little things you can solve easily. You want them to focus on your ideas and structure more than typos.

Fix the things you can, then send it to a reader.

Original:

“Online learning has its own unique challenges however opens the doors to a larger audience” (monexatb, 2020).

Corrected:

Online learning has its own unique challenges. However, it opens the door to a larger audience.

Test Early

Get feedback early. Share a whole or partial draft. See how readers react. Find out what they understand and what they don’t.

Discover how close you are to meeting the target reader’s needs and expectations.

Let’s say you are making an argument about a contemporary issue. To know if you’re meeting readers’ needs, you require certain feedback:

- Is your thesis clear?

- Are your reasons clear?

- Is your evidence accurate and considered trustworthy?

- Do you yourself come across as credible and trustworthy?

Know that it’s hard to see your own work through a reader’s eyes. There is no substitute for getting feedback. Strive hard to overcome the fears we all have about sharing our written work. Feedback is one of the most valuable parts of the writing process!

Consider the following exchange, in the comments thread below an op-ed.

“The highest % of funds are spent on the capital costs for constructing large buildings” (monexatb, 2020).

“[L]argest, by far, component of university budgets is salary, not capital costs” (ToryForever, 2020).

Read the exchange here.

Here, the respondent points out a correction.

This pair of comments illustrates the kinds of things that might come up in a reader’s response to an essay draft.

Don’t write in a vacuum. Find out what readers think and have to offer.

Tips

- Get feedback early and often.

- Give readers specific questions. What exactly do you want feedback on? The language and tone? Your argument? The structure?

- If you can’t find someone to give feedback, go over your own work with a second reader’s eyes as best you can. It’s very challenging to read something of yours as if you’re not the writer, which is why feedback is so important—but it’s always worth a try.

Refine Continuously

Develop your ideas based on feedback.

Let’s go back to the last example. Imagine you’re critiquing Mark Kingwell’s criticism of online teaching and learning. You’re making the point that online teaching will save money:

ORIGINAL

“The highest % of funds are spent on the capital costs for constructing large buildings” (ToryForever, 2020).”

See the source.

Now imagine that you receive the feedback that you’ve made a factual error. You do a little bit of research and verify the feedback. How might you revise?

One option is to delete the statement entirely. But you don’t have to.

You’ll need to question your own claim that online learning will bring significant savings to postsecondary institutions. But that doesn’t mean you have to abandon your line of thinking. You just need to refine it:

FEEDBACK-BASED REVISION:

While capital expenditures are a relatively small part of postsecondary budgets, the savings brought by online learning would still be meaningful.

The revision fixes the factual error and backs the point up with a source. It improves accuracy and credibility.

This revision reverses the statement about spending, yet makes fundamentally the same point: online learning saves postsecondary institutions money. It’s a much stronger claim now that it’s research-based and qualified.

The process is

- collect feedback;

- refine your work; and

- repeat the process.

Let’s end with one more example of what iterative design can look like in the writing process.

Let’s say you’re writing a critique essay evaluating Bruce Pardy’s claim that Mental disabilities shouldn’t be accommodated with extra time on exams,” and you’re getting input from readers on various drafts. What might these iterations look like?

| ESSAY DRAFT 3 | ESSAY DRAFT 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Critique essay—evaluates Pardy’s argument based on close analysis of his article | Research-based critique essay—evaluates Pardy’s argument based on both analysis and additional research into the topic of “student accommodation” |

| Updated Elements | Claim 1 (weakness of Pardy’s opening analogy that compares athletes in a race to students): adds additional example of a false analogy to clarify why Pardy’s analogy doesn’t work | Claim 1: adds research to solidify the claim and show alternatives to the “competitive” model of education |

| New Elements | New claim: adds a claim to address a reader’s observation of a weakness in the argument | Qualification section: adds a paragraph-length acknowledgement of the merits of Pardy’s argument |

Iterative writing is a great way to rapidly improve your work with the input of readers!

Try It!

Begin your journey with iterative design by putting users first.

To clearly understand the problem and the customer request. To feel humanely treated despite the fact that it’s a complaint.

To understand your thesis. To know the reasons why you feel as you do. To feel like their point of view is being treated fairly.

We covered what iterative design is and how it helps you focus on the needs of your audience. We explored how iterative design is a looping process of:

- Prototyping (making something to address others’ needs)

- Testing (getting feedback)

- Refining (improving the draft based on feedback)

Berger, G. (2020, May 25). May 25: ‘When done well, online education is much more than grainy videos.’ Is online education a pale shadow of the real thing? Plus other letters to the editor [Letter to the editor]. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/letters/article-may-25-when-done-well-online-education-is-much-more-than-grainy/

Daudelin, J. (2020, May 25). May 25: ‘When done well, online education is much more than grainy videos.’ Is online education a pale shadow of the real thing? Plus other letters to the editor [Letter to the editor]. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/letters/article-may-25-when-done-well-online-education-is-much-more-than-grainy/

Hohl, M. (2017, March 18). Prototyping: Iterative vs. parallel. The Medium. https://medium.com/ucsddesignco/iterative-vs-parallel-prototyping-575d455da5b5

Kingwell, M. (2020, May 19). Let’s admit it—online education is a pale shadow of the real thing. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-lets-admit-it-online-education-is-a-pale-shadow-of-the-real-thing/

monexatb. (2020, May 25). Re: Let’s admit it—online education is a pale shadow of the real thing [Comment]. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-lets-admit-it-online-education-is-a-pale-shadow-of-the-real-thing/

Pardy, B. (2017, August 17). Mental disabilities shouldn’t be accommodated with extra time on exams. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/opinion/bruce-pardy-mental-disabilities-shouldnt-be-accommodated-with-extra-time-on-exams

Simon, M. (2019, October 21). Pixel 4 vs every other Pixel: The newest Google phone might not be the best one to buy. PC World. https://www.pcworld.com/article/3446919/pixel-4-pixel-4-xl-pixel-3-pixel-3a-versus-features-specs-comparison.html

ToryForever. (2020, May 25). Re: Let’s admit it – online education is a pale shadow of the real thing [Reply to comment]. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-lets-admit-it-online-education-is-a-pale-shadow-of-the-real-thing/

Develop Voice

What you write is an extension of yourself, a little bit of your personality shows up on the page. Shape the personality of the writing you send out in the world.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why voice matters

- How context influences voice

- Strategies for shaping voice

Writing is social. For it to work, there needs to be some personality on display:

“Last week my wife and I told our 13-year-old daughter she could join Facebook. Within a few hours she had accumulated 171 friends, and I felt a little as if I had passed my child a pipe of crystal meth” (Keller, 2011).

Read the source here.

This writing sparkles!

Inject life into your prose. Say real things to real people.

Voice Matters

It’s normal for writing to come out a bit flat in the early drafting stage. At that stage, it’s often hard enough just to get ideas down!

This is probably especially true for academic writing and projects we don’t choose for ourselves.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there are a lot of things people can learn from the challenges already being faced by chronically ill people.

The idea matters.

Yet the eyes glaze over. There’s no colour, emotion, or spark.

It’s a bit like the writer is sitting expressionless at a party. We don’t know who they are, and we’re going to lose interest fast.

Without voice, writing can’t be social—or interesting!

When revising, transform a flat-sounding draft into something with character.

Context Matters

The fact that good writing has a voice doesn’t mean all your writing has to be full of huge gestures and humour.

A thoughtful, eloquent voice may suit who you are or may fit the situation, as in this meditation on the act of writing by author Jhumpa Lahiri:

“The urge to convert experience into a group of words that are in a grammatical relation to one another is the most basic, ongoing impulse of my life. It is a habit of antiphony: of call and response” (Lahiri, 2008).

Maybe your purpose and subject matter demand a factual, serious, scholarly tone:

“For most of the century between the two Reconstructions, the bulk of the white South condoned and sanctioned terrorist violence against black Americans” (Bouie, 2015).

In short, writing situations limit and define the possibilities of voice.

Who are you writing for? Why? Where are you sharing or publishing?

American comedian and actor Mindy Kaling can post a tweet like this:

“Speaking of movies I absolutely loved #TheWayBack. My man Ben Affleck crushed it. Such a moving movie about the healing power of sports, and this is coming from a person who tripped on her treadmill this morning. And my sis @Janina was Fire! Highly rec” (Kaling, 2020).

That tone would be disastrous in a bank’s annual report, which has to sound like the voice of corporate marketing:

“At CIBC, we are committed to delivering sustainable earnings growth to our shareholders and creating a relationship-oriented bank for our clients” (CIBC, 2019).

Read the report here.

Context shapes voice.

Be aware of who you’re writing to, and why.

Voice Is Attitude and Connection

Think of voice as attitude. Besides context, attitude depends on lots of things, such as:

- Your feelings

- Your personality

- The subject

In sum, voice is personality, the sense of an authentic person behind the written or spoken word.

With those points in mind, how can we cultivate voice?

We’ll look at three key strategies:

- Perspective

- Tone

- Style

Tip

Craft a voice that connects you to the people you want to reach, that shows them who you are and what you value, and that suits what you’re writing about.

Have a Perspective

Commitment to your topic or subject matter shows.

Some writing tasks are given to us. We don’t ask for them.

In those cases, find something about the topic that interests you. A fresh angle. A new idea to offer. Something all yours and just for your readers.

If the topic doesn’t interest you, maybe your own process of analysis does.

For instance, if you’re writing a critique essay or report, your focus may be your own evaluation of the source, event, or whatever you are analyzing.

Let’s say you’re asked to write a critique of Bill Keller’s “The Twitter Trap,” where he argues that social media is dumbing us down.

In your argument, you will engage with the subject of social media and its effect on us. But whether or not that subject matter interests you, your real focus is the way Keller builds his claims.

In this case, you’ll have a viewpoint on Keller’s own rhetoric and method of argumentation, not just the topic of social media.

Let the process of exploring Keller’s method of argumentation be what interests you.

There’s a lesson in Keller’s work itself. Bill Keller is passionate about his viewpoint, which comes through in many places in his essay through his original language and clear, ethically committed position:

“Typing pretty much killed penmanship. Twitter and YouTube are nibbling away at our attention spans.”

“Basically, we are outsourcing our brains to the cloud.”

“[Twitter] is the enemy of contemplation.”

“The things we may be unlearning, tweet by tweet—complexity, acuity, patience, wisdom, intimacy—are things that matter.” (Keller, 2011)

A critique of Keller can be just as committed, just as rooted in a perspective.

Let’s demonstrate this idea through a comparison. Here are two examples of a critique, both of them less committed than they could be. One supports Keller, one disagrees with him. Both are definitely starting to stake a position. But both could do more to create an authentic voice:

Keller makes a strong argument that Twitter and social media are having a negative effect on society. His evidence and claims show how Twitter affects attention span, memory, and the serious discussion of important topics.

Keller has valid concerns, but ultimately makes a weak argument that social media is causing us to become dumbed down. Granted, there are some examples of empty, silly communication on social media. But social media is also a platform for engagement and discussion.

Notice that while these critiques sound more committed, they are also more rounded and qualified. Both statements hedge a little bit and point to other viewpoints than their own.

Committed does not mean uncompromising. It means conveying passion for, and interest in, your own argument or purpose, within the boundaries of your writing context.

If the writer’s not visibly invested, why should anyone else be?

Communicate with Tone

Tone is the mood of your writing.

It’s a powerful, efficient way of communicating. It indirectly yet relentlessly shows readers the author’s view of the subject.

In any given project, the mood of your writing might be funny, sad, serious, measured…. Anything is possible.

As always, it depends on your purpose and the situation. Are you writing an opinion piece? An academic paper? A business or technical report? A post? A speech? Are you writing out of anger? Joy? Curiosity?

But even within related contexts, there are many possibilities of tone.

These three examples all come from articles written in response to the early part of the COVID-19 crisis, specifically around April–May 2020. The first is Canadian, the second American, the third Indian.

For example, the following three passages all relate to the same topic (vulnerable populations affected by the COVID-19 crisis) and appear as articles for a general readership in newspapers and magazines. Similar contexts. Similar topics. Different tones.

In the first, the personality of the writing is casual and clever, even though the topic is serious:

“We’re living in some wild times. A virus is on the loose, people are being quarantined, and many of us haven’t left our apartments in days. It feels like science fiction. Or, if you’re a chronically ill person, it feels pretty close to reality” (Feldman, 2020).

Read the source.

What makes this example feel casual and witty, like a friend is in the room, chatting with you?

- Informal writing (“wild times,” “pretty close”)

- Colourful language, including personification (“a virus is on the loose”)

- Ironic reversal (“It feels like science fiction. Or, if you’re a chronically ill person, it feels pretty close to reality.”)

Considering the topic—chronic illness—another fitting voice might be compassionate:

“As anyone who lives with chronic illness knows, life in a holding pattern is stressful. During an illness flare, each day bleeds into the next as we wait and wait and wait for things to get better. It’s tiresome and boring. As if that’s not enough, we are acutely aware that things could get worse. Our health could slide fast, leaving us longing for the boredom over pain and terror. Anxiety mixes with tedium to produce an unwelcome cocktail.

“We’re all in that space these days [during COVID-19]. We’re fatigued, agitated, and lonely. We long for normalcy—to go to work, to celebrate milestones together, to be part of the humming of the world” (Virant, 2020).

Read the article here.

How does the writer’s sense of empathy come through?

- Serious language (“illness flare,” “acutely aware,” “longing for the boredom over pain and terror”)

- The way the writer draws special attention to—or heightens—the suffering of chronically ill people, for example in the repetition of the verb “wait” (“we wait and wait and wait for things to get better”)

- The voice of a collective to which the writer belongs, through the use of the first-person plural pronoun (“we wait,” “our health”)

- The connection drawn between the chronically ill and everyone else (“We’re all in that space these days”)

The writer never says, “I have compassion for the plight of the chronically ill.” In fact, a direct statement like this would probably sound insincere. The writer’s tone communicates her compassion.

The voice could also be formal and serious:

“Ever since the lockdown began, stories of migrant workers have haunted [India]. These stories of suffering and hardship have become the face of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in India’s megacities. There is an eerie similarity to many of them, highlighting an unequal society that has caused a humanitarian crisis to erupt during an unprecedented health crisis” (Priyam & Bordoloi, 2020).

Read the entire article here.

What makes this writing formal?

- The use of third person, where a seemingly neutral, disembodied voice is speaking about a third party (the migrant workers). As readers, we’re more distanced from the author and the subject matter than in the examples above. This is neither better nor worse—just different, with a different effect.

- Formal language (“…that has caused a humanitarian crisis to erupt during an unprecedented health crisis.”)

Even short extracts from each piece are enough to see the distinct tones and personalities in the writing.

Write with Style

Like tone, style is about the way you communicate something, as opposed to the literal content. But where tone is synonymous with mood, style is more about the arrangement and patterns of words and sentences.

For our purposes, style is the shapes and sounds of your sentences, and the special, original choices you make (such as using fresh figures of speech).

Consider these three passages, and notice how characteristics of style do a lot to shape the voice that comes through:

Here the style is blunt. It’s also kinda informal. I’m using mostly short sentences, some slang. A fragment or two. You get the picture. It’s writing done more like speech.

Listen now to the change in style. Because I’m using periodic sentence structure, where the main clause is delayed, and parallelism, where several corresponding grammatical chunks (nouns, phrases, clauses) stem from the same root, and because the lexis is more complex, the style sounds less like speech. That doesn’t mean it has to be especially dense and difficult. Nor that all the sentences must be lengthy. Very much the opposite. The point is, the overall effect is more formal, and the pattern of thought is different.

Style is music. This short passage aims for sonority and rhythm—a beat, a pulse. Writing it, I’m alert to combinations of vowels and the clash of consonants. I want some sentences that drift, and turn, and softly close on words of several syllables. And other lines that hurtle to a rhythmic end.

Don’t feel you have to learn a lot of grammar and prosody to write with style! It’s not about the rules and the labels. It’s about listening to your own style, experimenting with it, and actively shaping your sentences.

That said, here are a couple of quick sentence patterns and other tools it’s good to be aware of:

1. Vary Sentence Length

Use lots of short sentences. They are easier to read. They take a load off your readers. Readers appreciate them. But not too many in a row! Otherwise the writing becomes monotonous. Like here.

By contrast, this paragraph contains variety. Some sentences are short. Others, like this one, are slightly longer and consist of more than one phrase. Only once does sentence length in this paragraph exceed 15 words, and if you want to reach a wide audience, make about 20 words your upper limit. The point is, vary the sentence length!

2. Place Your Main Clause Deliberately

Do you know where your main clause is?

Ok, that is one piece of grammar terminology you should make sure you know.

Understand the difference between an independent clause (often called main clause when it’s the only independent type in the sentence) and subordinate clause.

- An independent clause has a subject and verb and can stand alone as grammatically complete, although it’s often embedded in longer sentences.

- A dependent clause also has a subject and verb but cannot stand alone, except as a

fragment. It is grammatically dependent on some other part of the sentence. It’s marked by something called a subordinating conjunction (as long as, because, since, though, which, etc.):

- subordinating because it marks the clause as dependent; and

- conjunction because it joins the clause to some other part of the sentence.

Let’s look at some examples. Pay attention to where the main or independent clauses are (underlined in each example):

This sentence is a single independent clause.

This sentence has two independent clauses, and it joins them with the word “and.”

Because it begins with a subordinate clause and builds towards the main idea, this sentence is a distinct but common type called “periodic.”

This so-called “cumulative” sentence starts on the main clause, which is then followed by any number of additional phrases or clauses that qualify or enlarge our understanding of the idea.

For more information, see this resource.

And while we’re at it:

Beginning with a participial phrase, this sentence demonstrates a very common pattern you should study.

Want to solidify your knowledge of this pattern? Look up participial phrase here.

3. Use Figures of Speech

Common figures of speech include simile and metaphor, which are both types of comparison.

A simile compares two things with “like” or “as”:

“The best sentences orient us, like stars in the sky, like landmarks on a trail” (Lahiri, 2012).

A metaphor compares two things as if they are identical, as if one thing is not merely like another but is that thing:

“The first sentence of a book is a handshake, perhaps an embrace” (Lahiri, 2012).

Used sparingly, figures of speech enhance voice and clarify thought, and therefore build connection to the reader.

Tip

Avoid clichés, which are tired or overused figures of speech or other expressions. “Sick as a dog” and “He’d give you the shirt off his back” are two examples. Avoid non-figurative generalizations, too, such as “In today’s society….” When revising and editing, replace overused expressions with something fresh and original.

Voice Changes

Nobody has one single “writing voice” or “speaking voice.” Our sound—our personality—changes according to context. There may be a common thread or a dominant voice in your output, but it’s ok if your voice changes.

As you go forward, think about how you can do more to bring your communications to life by cultivating different voices for your different writing situations.

Each time, use the power of voice to connect with others!

Your Right to a Voice

A parting thought: When you craft voices to connect with others, you also create space for your voice(s) to be heard. If your culture has historically silenced people from the groups you identify with, this act may be especially significant.

As Rebecca Solnit says, “Having the right to show up and speak are basic to survival, to dignity, and to liberty. I’m grateful that, after an early life of being silenced, sometimes violently, I grew up to have a voice, circumstances that will always bind me to the rights of the voiceless” (2012).

https://www.guernicamag.com/rebecca-solnit-men-explain-things-to-me/

At one level, developing “voice” is technical. At another, it becomes the same as striving to “show up and speak” and “have a voice,” sometimes in the name of those who remain voiceless.

Instructions:

Click on the buttons below for some writing prompts that help you practise crafting different voices. In the panel that opens for each, you can click on further suggestions as needed.

Try the exercises in your favourite software. Feel free to use the text editors provided, but remember that your responses will not be saved.

1. Description of Space

2. Opinion and Critique

Voice is the personality of your writing. For every piece you write, it’s important to be aware of voice in general and to cultivate the particular voice you’re developing for that project.

Think about perspective (fresh angles, unique insights) and tone (the mood you convey) to craft the voice of your writing.

Engage your readers—make them feel like you’re a real person writing real things that should matter to them!

Bouie, J. (2015, February 10). Christian soldiers. Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/02/jim-crow-souths-lynching-of-blacks-and-christianity-the-terror-inflicted-by-whites-was-considered-a-religious-ritual.html

CIBC. (2019). 2019 annual report. https://www.cibc.com/content/dam/about_cibc/investor_relations/pdfs/quarterly_results/2019/ar-19-en.pdf

Feldman, M. (2020, April 11). What we can learn about “distant socializing” from chronically ill trauma bbs. Shameless. https://shamelessmag.com/blog/entry/what-we-can-learn-about-distant-socializing-from-chronically-ill-trauma-bbs

Kaling, M. (2020, March 25). Speaking of movies I absolutely loved #TheWayBack. My man Ben Affleck crushed it. Such a moving movie about the healing [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/mindykaling/status/1242961017963008001

Keller, B. (2011, May 18). The Twitter trap. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/22/magazine/the-twitter-trap.html

Lahiri, J. (2012, March 17). My life’s sentences. New York Times. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/17/my-lifes-sentences/

LastWeekTonight. (2018, September 23). Facebook: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OjPYmEZxACM

Priyam, M., & Borodolio, M. (2020, May 28). Documenting the story of India’s migrant distress. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/documenting-the-story-of-india-s-migrant-distress/story-sVC8sCHFetXYBPKLa1OhZM.html

Solnit, R. (2012, August 20). Men explain things to me. https://www.guernicamag.com/rebecca-solnit-men-explain-things-to-me/

Traffis, C. (2020). What is a subordinating conjunction? Grammarly Blog. https://www.grammarly.com/blog/subordinating-conjunctions/

Virant, K. W. (2020, May 15). COVID-19 and chronic illness. We won’t be marginalized as the country re-opens. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/chronically-me/202005/covid-19-and-chronic-illness

When can government restrict speech? | Nadine Strossen [Video]. (n.d.). Big Think. https://video.bigthink.com/m/vOGRPxGK/when-can-government-restrict-speech-nadine-strossen?list=KYTkXdhA

Be Concise

More meaning. Fewer words.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why concision matters

- How to trim your writing

- Three quick strategies that always work

First drafts are for free. Use all the words you need to generate your ideas:

One of the big problems in communication is when readers are forced to wade through far more words than they need to get fundamentally the same meaning. (27 words)

But then go back and trim unnecessary words:

A key communication problem is using more words than needed to express the same meaning. (15 words)

Go further. When relevant, focus on solutions. Propose actions. These lend themselves to concise, razor-sharp points:

To help your readers, trim unnecessary words. (7 words)

Why Concision Matters

Imagine you’re critiquing an argument.

Consider the following passage:

The argument made by the author as to why the government is not doing enough for the wellbeing of Indigenous communities is strong and reliable because the article provides evidence that is effective, accurate, and reliable, which makes the author’s points valid.

The idea is important! But that’s a lot to chew on!

How can we improve this?

Try these strategies:

- Trim

- Cut redundancy

Let’s see these strategies in action.

Tip

Remember, your writer-focused draft can be anything. The key is, revise so it’s reader-focused. The wordy sentence above is not wrong. It’s how the writer got the idea down. But readers need the revision!

Trim

Let’s trim, or cut unnecessary words.

Consider:

The argument made by the author as to why the government…

Let’s take a closer look at these cuts:

First, use “The author’s” instead of “made by the author”:

The argument made by the author The author’s argument

Now, replace a three-word phrase with one word:

as to why that

The result?

The argument made by the author as to why the government… The writer’s argument that the government…

Combined, these changes reduce the opening from 11 words to six. Almost half the length! Yet with no loss of information.

Tip

Concise writing is your complete meaning in the fewest possible words.

Cut Redundancy

Redundancy is unnecessary repetition. It comes in at least two forms:

- Piling up synonyms

- Stating info the reader does not need, because

- it’s a given (like telling a chessmaster the rules of the game); or

- you’ve already implied it; or

- it’s beside the point.

Look again at the original passage. (The main idea is in boldface):

The argument made by the author as to why the government is not doing enough for the wellbeing of Indigenous communities is strong and reliable.

Do we need both “strong” and “reliable”? No! They’re close enough in meaning.

Don’t pile up synonyms.

Also, don’t repeat the word “reliable.” The original says the argument is “strong and reliable,” and the evidence is “accurate and reliable.”

Let’s just say, accurate evidence leads to a strong argument.

Tip

There has to be a really good reason to use two terms when one will do!

Don’t stop at single words. Cut whole clauses, sentences and ideas:

The argument … is strong and reliable because the article provides evidence that is provides effective, accurate, and reliable evidence, which makes the author’s points valid.

Do we need “which makes the author’s points valid”?

Maybe. It depends on how important the idea of validity is here.

If it’s not central, cut it.

Putting It All Together

The revisions below mean the same thing as the original passage. But they’re concise.

Revision 1

The author’s argument that the government is not doing enough for Indigenous communities is strong because it’s based on accurate evidence.

Revision 2

Drawing on accurate evidence, the author convincingly argues that the government is not doing enough for Indigenous communities.

The term “convincingly” implies that the argument is strong, reliable, and effective. We can cut all those terms.

Revision 3

While concise, revisions 1 and 2 above could sound more natural:

The author argues that the government is not doing enough for Indigenous communities. The claim is strong and just, backed up by accurate evidence.

Going Further

We have a concise, natural-sounding version of the original. Next, let’s build it back into a longer statement. Not by padding out the same idea, but by adding new ideas.

By revising for concision, we’ve freed up space. Now we can push further and build the argument.

Recall the original:

The argument made by the author as to why the government is not doing enough for the wellbeing of Indigenous communities is strong and reliable because the article provides evidence that is effective, accurate, and reliable, which makes the author’s points valid. (42 words)

Here’s a sample revision. Notice it’s three words shorter, but says far more:

I accept the author’s claim that the government is failing Indigenous communities. The evidence is accurate, the reasoning sound. The question is, what then? First, I’ll look more closely at the argument’s strengths, then explain why it matters today. (39 words)

In the first half of the revision, which is fewer than 20 words (up to the word “sound”), we say what took twice as many words before.

In the remaining 20 words (the second half of the revised version), we push into new territory, explore implications, and create more interest and anticipation.

We say more with less.

Try it!

Test Your Knowledge

Which of the following best defines concision?

Try It Out!

The author’s point that coronavirus communication must be reasonable and fact-based may help reduce misinformation, and therefore panic.

You can write concisely by:

- Trimming

- Cut unnecessary words

- Compress your language (“as to why” = “because”)

- Cutting redundancy

- Cut synonyms

- Cut direct statements of what is already implied

By writing concisely, you make room to push your ideas into new territory. Your writing becomes at once clearer and lighter yet richer in information.

Be Clear and Complete

Don’t leave people guessing what you mean. Be clear and direct, and use lots of examples.

What You’ll Learn:

- Strategies for clarity

- Strategies for completeness

Clarity and Completeness Defined

Clarity

Clarity means readers don’t have to ‘decode’ to understand your meaning:

- Points are clear, direct, straightforward.

- Words are precise but common.

- There’s no filler. (See Concision)

- Sentences and paragraphs are short (with enough variation to keep things interesting).

- There are definitions, examples, and explanations so the meaning is complete.

When in doubt, use plain language, language people can understand on a first reading.

Completeness

Completeness means you’ve left nothing out that your reader needs in order to follow along:

- Ideas are fully explained.

- Terms are defined.

- Context is provided, so readers know why you’re writing and how the ideas relate to the larger world.

- Examples are used wherever appropriate, to illustrate abstract concepts.

Two qualifiers:

- In some contexts, people expect more dense, complex, or indirect language. For instance: some academic writing, along with poetry, fiction, and other personal, expressive forms of writing. “Look at the old house/ Outmoded, dignified/ Dark and untenanted/ With grass growing instead/ Of the footsteps of life” (Thomas, n.d.). Read the original poem here.

- Discipline-specific writing is also not always written for the “general reader,” but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s unclear. For example, the following statement is unclear to a layperson, but perfectly clear to a software specialist, because the grammar and syntax are clear and the terms are precise: “If I had this requirement, I would probably solve it by creating a base class for my serializers (which I always do anyway for key transforms and other shared behavior [sic]), and then copy the parameter on init” (christophersansone, 2019). (https://github.com/fast-jsonapi/fast_jsonapi/issues/21)

Strategies for Clarity and Completeness

Fix Sentence Structure and Ambiguous Words

Ambiguity refers to “inexact meaning.” It happens in at least two ways:

- Grammar, syntax, and word choice make the meaning unclear.

- A word, phrase, or sentence is unintentionally open to two or more equally possible interpretations.

People who don’t know specific people of a certain gender identity could create biases because of their portrayal in the media.

Here are some questions a reader might have:

- Which of the two “people” nouns does the pronoun “their” refer to?

- Does the writer intend the meaning “People … could create biases”?

- What does the writer mean by the phrase “a certain gender identity”?

Solutions may include the following:

- Be clearer and more specific than the term “gender identity.”

- Clarify who or what “creates” biases—here, it’s stereotypical media portrayals.

- Make the clause “People who don’t know specific people of a certain gender identity” more natural and concrete: “those who have no direct personal experience of transgender identity.”

Consider this revision:

Historically, transgendered identity has been misrepresented and stereotyped in the media. False media portrayals encourage biases among those who have no direct personal experience with transgender people.

Define Terms

Define specialized terms, even relatively common ones that you assume people are familiar with.

In the following passage, the writer defines the term “obsessive-compulsive disorder”:

“I have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a mental disorder characterized by intrusive thoughts or feelings (obsessions) that can lead an individual affected to engage in behaviours (compulsions) that alleviate the anxiety that can come with intrusive thoughts. My OCD is mostly obsessive with compulsive behaviors thrown in under high stress” (Hannah, 2020).

Read the source.

Remember:

First ideas are for free. Draft however you need to in order to get your ideas down. Then stand back from your writing and ask yourself where readers are likely to get confused. It’s always challenging to review your own work from an external reader’s perspective, so you should also get feedback from real readers. Ask them where they don’t follow your ideas. Fix the problem areas. But don’t sweat the fact that there are problems! A first draft of anything worthwhile always has them.

Be Precise and Concrete

Consider this statement:

Plastic is bad.

What does this mean? How is plastic bad? What does the writer mean by the term “bad,” anyway?

Considering that plastics are light, tough, cheap, and highly useful in construction and electronics, they can’t be uniformly bad.

In short, the statement is unclear.

The following alternatives are clearer because they are more precise (specific):

Plastic is bad for the environment.

Plastic is environmentally harmful.

The unclear statement (“Plastic is bad”) might come from a writer who is picturing environmental effects or assuming readers are doing the same.

That’s dangerous. When writing, get your assumptions out of your head and onto the page.

The following statement is even clearer and more precise:

Plastic harms ocean life.

Why is this statement an improvement? Because it’s even more precise, and it’s concrete.

Concrete means things you can sense—see, touch, hear, taste, smell.

The terms “environment” and “environmentally” are abstract. It’s hard to picture “environment,” and if you try, there are dozens of things you could think of—birds, trees, a forest, a waterfall, a climate protest, a nature show complete with narration, soundtrack and high-definition images…. It’s different for everyone.

An “ocean” everyone can visualize right away and agree on. It’s concrete.

Add Context

Context means the bigger picture. Context positions your idea in relation to the world around it:

Plastic is everywhere and we can’t avoid it—but it’s harming the oceans.

Now we have more context for the statement that plastic is harmful: It’s everywhere, and its use is seemingly unavoidable.

With context, we better understand why the writer is drawing our attention to the harm of plastic on ocean life. We see that the problem is urgent because it doesn’t have an easy fix.

Provide Examples

Consider this improved version, which comes directly from the original article:

1 Avoiding unnecessary plastic is not just hard, it’s nearly impossible. Bags, take-out food containers and other single-use plastic items spill out of our recycling bins and litter our neighbourhoods. Now we have more data than ever on how plastics are killing our oceans.

2 “You might want to sit down for this: the equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic enters our oceans every minute. Mistaking it for food, one in three sea turtles, some 90 per cent of seabirds and more than half of all whales and dolphins have ingested plastic. (Khan & Alfred, 2018)

See the source here.

In paragraph 1, the writers use concrete examples to illustrate the concept of how hard it is to avoid plastic:

- Bags

- Take-out containers

- Other single-use plastic items found in recycling bins and forming litter on the streets

At the end of paragraph 1, the writers make a precise, forceful claim about the effect of plastic on oceans: “Now we have more data than ever on how plastics are killing our oceans.”

Immediately following, in paragraph 2, the writers illustrate this claim with more vivid examples.

Clarity and Completeness in More Abstract Writing

It’s relatively easy to solve issues of clarity and completeness when you’re writing about concrete subjects. You can reach for concrete examples more easily.

What do you do if you’re writing about abstract things, such as concepts and arguments?

The techniques are pretty well the same:

- Be as precise and concrete as possible.

- Contextualize your ideas.

- Define terms.

- Provide examples.

Suppose you’re writing a critique of Bruce Pardy’s argument against accommodations for difference and disability.

If you judge Pardy to be mistaken, your critique might circle around the following idea:

Pardy is wrong.

As it stands, this point is ambiguous and incomplete. (Also, the tone is harsh and dismissive, which is something else we can correct at the same time.)

In 2017, Bruce Pardy, professor of law at Queen’s University, wrote a public opinion piece based on one of his academic articles, in which he argues that it’s unfair to provide extra time on exams for people who identify as having learning disabilities. He claims that the entire point of a timed exam is to “discriminate” between (select among) those who can perform up to standard in the allotted time and those who—for whatever reason—cannot do so.

Here’s a clearer version:

1In a special for the Canadian newspaper National Post, “Mental Disabilities Shouldn’t Be Accommodated with Extra Time on Exams” (2017), Professor Bruce Pardy argues that accommodations are unfair to students who do not require them. Given enough time, anyone could perform up to standard. But the point of a timed test, he argues, is precisely to see who can perform up to standard in the allotted time, and who cannot.

2 Pardy’s desire to protect academic integrity is understandable. That said, it’s a problem that his argument privileges some types of students and excludes others. However, before even looking at that problem, I want to suggest some different, broader ways to think about how to measure student learning.

3 Pardy assumes education is competition. 4 For instance, he compares accommodations to a runner gaining an advantage in a race:

Last week at the World Track and Field Championships, Usain Bolt ran his final race. Andre De Grasse, the Canadian sprint star, missed his last chance to beat Bolt because of a hamstring tear. If, instead of pulling out of the race, De Grasse had claimed accommodation for his injury and demanded a 20-metre head start, no one would have taken the request seriously.

Yet an equivalent accommodation is standard practice at Canadian universities and colleges. They award extra time on exams and assignments to students who claim mental and cognitive impairments. Extra time for mental disabilities is as unfair to other students as a head start would be to other runners. (Pardy, 2017)

On a first reading, this analogy seems compelling. 5 But there’s a different way to think about it. The entire point of a race is to see who’s fastest. Arguably, the primary purpose of a classroom test is to measure what a student knows and can do, and only secondarily, if at all, to see how fast a student can perform. Increasingly, educators are calling into question the idea that speed relates to skill and ability (see Blodget, 2019). Is speed a valid criterion?

How can we broaden the idea of “education” beyond “testing”? 6 There are many alternatives to the timed test, including simulations and e-portfolios (see Wingfield, 2014).

1 Context: Where Pardy’s argument comes from and what it’s about

2 Precision: A much more specific response than “Pardy is wrong”

3 Clarification: Zeroing in on part of Pardy’s argument

4 Example: Specific passage from Pardy’s argument that illustrates the preceding point

5 Clarification: Redefinition of what tests should measure

6 Example: Researched alternatives

Additional Strategies

Here are a few final pointers for making your writing clear and complete:

- Use strong, active verbs, not passive ones: “The study showed that…” instead of “It was shown in the study that…”

- Use common words: “This idea emerges grows out of…”

- Use headings, subheadings, and ordered (numbered) or unordered (bullet point) lists.

- Use graphics and graphic organizers wherever possible or appropriate (images, tables, etc.).

Examine the following “unclear stems” (vague and/or confusing statements). Choose one or several of these stems, and write clearer, more complete statements about the topic in the text editor below. Use research, as needed, to develop and define your ideas. Some sources have been provided, but you can use your own research as well. You are welcome to switch position on the topic or keep it the same as in the original.

“Millennials are coddled and selfish, which can be extrapolated from the issue.”

RESEARCH

- Lincoln Anthony Blades, “Millennials Are Not Entitled” (3-min video). https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/892319299873

- Goali Saedi Bocci, “Are Millennials More Than an Entitled Generation?” https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/millennial-media/201909/are-millennials-more-entitled-generation

“Genetic technologies are dangerous and need to be banned at all levels.”

RESEARCH:

- John Oliver, “Gene Editing” (20-min video). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AJm8PeWkiEU&t=267s

- “The Basics of Genetic Engineering” https://sites.psu.edu/english202geneticengineering/pros-and-cons/

Make sure your writing and other communications are clear and complete, so that your audience will have no trouble quickly understanding your intended meaning. Strategies include:

- Fixing sentence structure and ambiguous wording

- Defining your terms

- Being precise and concrete

- Adding context

- Using examples

The basics of genetic engineering. (n.d.). Penn State. https://sites.psu.edu/english202geneticengineering/pros-and-cons/

Blades, L. A. (n.d.). Millennials are not entitled [Video]. CBC Viewpoint. https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/892319299873

Blodget, A. S. (2019, September 30). It’s time to end timed tests. Education Week 39(7). https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/10/02/its-time-to-end-timed-tests.html

Bocci, G. S. (2019, September 23). Are millennials more than an entitled generation? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/millennial-media/201909/are-millennials-more-entitled-generation

christophersansone (username). (2019, December 16). Allow conditional relationships to see what’s been included [Discussion thread]. Github. https://github.com/fast-jsonapi/fast_jsonapi/issues/21

Hannah, R. P. (n.d.). Marriage, OCD, and Covid-19. abilities. https://www.abilities.ca/top-stories/what-its-like-to-have-a-6-feet-apart-marriage-due-to-covid-19/

Khan, F., & Alfred, E. (2018, April 20). Plastics bomb: The throwaway culture pushed by corporations is killing our oceans. Now Magazine. https://nowtoronto.com/news/plastics-killing-oceans/

LastWeekTonight. (2018, July 1). Gene editing [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AJm8PeWkiEU&t=267s

Pardy, B. (2017, August 27). Mental disabilities shouldn’t be accommodated with extra time on exams. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/opinion/bruce-pardy-mental-disabilities-shouldnt-be-accommodated-with-extra-time-on-exams

Plain Language Action and Information Network. (n.d.). What is plain language? https://plainlanguage.gov/about/definitions/

Simmons, R. L. (2020). The participle phrase. Chomp Chomp. https://www.chompchomp.com/terms/participlephrase.htm

Singh, S. (2018, August 4). What are the advantages of plastic? [Forum response]. Quora. https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-advantages-of-plastic

Thomas, E. (n.d.). Going, gone again. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/53747/gone-gone-again

Wingfield. M. (2014, August 13). What are the alternatives to exams in vocational education? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/aug/13/alternatives-academic-exams-vocational-education

Be Correct in Context

Correct your work according to context. Provide accurate content and consistent presentation.

What You’ll Learn:

- How to correct things depending on context

- How to protect factual accuracy

We communicate differently in different situations.

What counts as “correct” depends on that situation, and depends on whether we’re speaking or writing, writing a tweet or an essay, presenting at a conference or chatting with a friend.

For instance, in many types of writing, it’s considered incorrect to use:

- Sentence fragments (grammatically incomplete sentences, such as “Arranging the ideas,” or a one-word sentence like “Right.”)

- Contractions (“won’t”)

- Interjections (“yeah,” “oh”)

But in many spoken English contexts, it would be incorrect to avoid these, and a series of grammatically complete sentences would be wrong.

Being correct according to context is an important communication tool.

We’re going to use the word correct in another sense, meaning factually correct. Here, “correctness” is or should be less dependent on context, more absolute or universal. It’s never ok to willingly distort facts, and we must always check facts for mistakes and hold others to the same high standard.

Correctness in Context

When we say “be correct in context,” we mean pay attention to the rules and conventions of the context you’re in.

Dealing with Rules

You can follow the rules. You can break rules, too, but you should always be aware of the possible effects on readers and consequences to you as a writer.

For example, if you’re an engineering technician student in Ontario, Canada, you’ll need to prepare a report according to the rules set by the Ontario Association of Certified Engineering Technicians and Technologists (OACETT).

Here are four of the style and language guidelines for that report:

- The document should be typed, double-spaced using Arial, Univers, or a similar Sans Serif 12-point font.

- The lines should be justified left, with pages numbered and appropriate page breaks.

- Correct spelling, punctuation, and grammar should be used.

- Consistent voice, subject-verb agreement, and verb tenses should be used.

Read the source.

You’re always free to submit a report that is single-spaced, uses serif font, and switches verb tenses frequently. But there are consequences.

Rules in Context: Becoming a “Polyglot”

Items 1 and 2 from the OACETT guidelines above are objective:

- You can measure whether a document is typed and double-spaced using sans serif 12-point font, left justification, and numbered pages.

- The size of 12-point font is standardized and is unlikely to change from one place to another, or to change over time.

- Any two or more people will be able to reach unanimous agreement on whether a given document follows those first two guidelines.

Items 3 and 4 are less objective because the rules of orthography (spelling, punctuation) and grammar do change from place to place, and over time.

There are so many types of written and spoken English, and so many kinds of English speaker and English language learner, that it’s probably better to be able to adapt to many contexts and learn the conventions of different contexts than to “learn the rules,” as if there’s only one set.

Like a programmer who knows many computer programming languages and can pull out the right one for the job, you should become familiar with many different kinds of English (and other languages, if possible) and learn how to adapt to the situation you’re in.

There is no one “standard” or “correct” English.

Correctness and Power

It’s important not to privilege one rhetoric, or form of language, over another.

For example, the English classroom in a North American postsecondary institution can easily feel like a place of judgment, where you sense you’re either “correct” or “incorrect” in your use of language.

But if you’re a student in that setting, remember that the conventions and rules taught there don’t replace other rhetorics you possess and shouldn’t be privileged over them, such as the way you speak and write with friends.

Academic and so-called “mainstream” English are only correct in certain contexts. In other contexts, their rules don’t apply and are sometimes incorrect.

Linguistic Accuracy

Finding Out the Rules

To “follow the rules” of grammar and usage in a particular context, you should look at relevant and reputable examples of the genre, and at relevant style guides.

For example, if you’re learning how to write journalism, read a lot of journalism from around the world, especially from your region and in the specific genres you’re interested in.

In many North American postsecondary institutions, when writing academic essays, you can follow the guidelines for style, layout, grammar, and more set out in one of these manuals:

- APA https://apastyle.apa.org/products/publication-manual-7th-edition/

- MLA https://style.mla.org/works-cited-a-quick-guide/

- Chicago Manual of Style https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/home.html

There are also popular, classic texts on grammar and style you can consult:

- Strunk and White’s Elements of Style

- Messenger’s Canadian Writer’s Handbook

If you are writing for a particular publication, you can ask if they have a house style manual.

Flexibility

In some writing situations, there’s a lot of room to experiment, bend rules, or blend rules from different contexts. In others, the rules are more rigid. You can still always bend or break rules, but the stakes and consequences change.

If you’re asked to prepare a paper according to APA style, then there are specific rules of grammar, layout, citation, and more.

If you’re writing a personal blog, social media post, or piece of creative writing, there are conventions and reader expectations, but you can theoretically do anything you want.

Factual Accuracy

We’ve looked at linguistic correctness and said that guidelines depend on context.

We’re going to look at another form of correctness—factual accuracy—and lay down a more universal principle.

Especially in the era of fake news, mass mobile communications, and information overwhelm, it’s more important than ever to uphold the standards of factual accuracy and to be able to distinguish between fact and opinion.

Is It Fact or Opinion?

A fact is a piece of information that can be proven with evidence. It may be accurate or inaccurate.

An opinion is a judgment shaped by personal beliefs, values, and assumptions. It may be informed or uninformed.

An informed opinion is generally an interpretation of available facts, whereas an uninformed opinion may be based on nothing but personal feeling or even prejudices.

See this source for further information.

For example, the following is a fact:

In 2016, 2% fewer Canadian postsecondary students than in 2013 felt their mental health was very good or excellent.

This happens to be an inaccurate fact. The accurate fact is the following (notice the correction of the statistic):

In 2016, 8% fewer Canadian postsecondary students than in 2013 felt their mental health was very good or excellent.

You can see how easy it is to intentionally or unintentionally distort a fact. The consequences can be significant. Two percent and 8% may seem close, but in statistical terms they are very different. The consequences of getting the fact wrong is serious.

Put simply: Facts matter.

Is the following fact or opinion?

Student mental health is worsening.

It’s an opinion, not a fact. It’s a judgment based on

- the statistical data (the fact of fewer students reporting good mental health); and on

- assumptions about how to interpret that data.

Just because the opinion is fact-based does not necessarily make it true or valid.

As this source points out, the statistical decline in students reporting good mental health may not mean that more students are suffering. It may mean that more students are willing to admit to having poor mental health or that more students are able to recognize and label it—in short that there’s more space for expressing mental health problems (Chiose, 2016).

We don’t know for a fact what’s at the root of the decline.

Here, then, is an alternative opinion—that is, an alternative interpretation of the facts:

Students are increasingly able to recognize signs of mental health problems and increasingly willing to admit when they are suffering.

One of these statements may eventually become a fact, if enough convincing evidence can prove it beyond a doubt.

Be a Fact-Checker

Always check your own facts before communicating them. Ensure that you are reproducing data accurately, and also that your sources are reliable.

Likewise, check the facts that others present, or at least check how reliable the sources in question are.

Sometimes you have to go through more than one layer of fact-checking.

For instance, the fact in the previous example, that 8% fewer students reported good mental health in 2016 compared to 2013, comes from a Globe and Mail newspaper article.

The Globe and Mail is a mainstream Canadian newspaper-of-record, meaning that it’s held to a high standard of accuracy and impartiality in its reporting.

That doesn’t mean it never publishes factual errors. But it’s a reputable source, and it publicly corrects errors it makes when these are drawn to the editors’ attention.

In turn, the Globe article was citing a statistic from the National College Health Assessment. So the next step would be to look at that source and determine its credibility.

As of this writing, the web page the Globe article linked to is no longer available. We might not be able to check it directly.

The process, though, remains:

- Check the sources of any facts you cite. How reliable is the given source? Why?

- What sources is that source relying on?

- Remember that methods for collecting data are not always reliable.

- Remember that facts can be distorted, invented, and made to appear credible when they aren’t accurate.

- Remember that all facts can be interpreted in multiple different, sometimes contradictory, ways.

Try it!

In “I Sure As Hell Wouldn’t Want to Be a Student Now: An Open Letter to Margaret Wente,” Elamin Abdelmahmoud challenges Margaret Wente’s point that students today are overprotected and fragile. He draws on firsthand knowledge: “I’ve had the pleasure and challenge of teaching the young people you write about. For the last two years, I’ve taught a course at Ryerson University in Toronto. Based on what I see, students don’t at all fit your description” (2017). While every writer has to speak from their own experience, and Wente can’t be faulted for having less direct experience, his words on the subject carry more authority.

Correctness in communication is important, and incorrectness can have serious consequences. At the same time, what counts as “correct” in language is not universal. It depends on context.

Learn how to be correct in various contexts, and learn how to find and apply the rules or guidelines required, rather than memorizing lists of rules.

When it comes to factual accuracy, we should be more absolute. Know the difference between fact and opinion. Learn how to vet sources for their accuracy, and always make sure to check your own work for factual accuracy and integrity.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association, seventh edition (2020). https://apastyle.apa.org/products/publication-manual-7th-edition/

American Psychological Association. (2020). Style and grammar guidelines. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/

Chiose, S. (2016, September 8). Reports of mental health issues rising among postsecondary students: study. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/education/reports-of-mental-health-issues-rising-among-postsecondary-students-study/article31782301/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

Modern Languages Association. (2020). Works cited: A quick guide. The MLA Style Center. https://style.mla.org/works-cited-a-quick-guide/

OACETT. (2017). Technology report guidelines. https://www.oacett.org/getmedia/9f9623ac-73ab-4f99-acca-0d78dee161ab/TR_GUIDELINES_Final.pdf.aspx.

Pew Research Center. (2020). Distinguishing between factual and opinion statements in the news. https://www.journalism.org/2018/06/18/distinguishing-between-factual-and-opinion-statements-in-the-news/

University of Chicago. (2017). The Chicago Manual of Style online. https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/home.html

Develop Flow

Connect your ideas so readers can follow.

What You’ll Learn:

- How to group and sequence ideas

- How to connect ideas

Flow in writing is the sense of connection between ideas.

Writers should:

- Group similar ideas together

- Order (sequence) ideas logically

- Connect each sentence to the next

Group, Sequence, and Connect

A first draft is exploratory. Even if you’ve planned and outlined your project, ideas might pour out at random. It’s not easy to write a first draft. Give yourself permission to write prose that doesn’t yet flow:

1 Students are greatly in debt. 2 In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. 3 Postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life. 4 Credentials are no longer enough for employment.

Statements 1, 2, and 4 relate to the pressures and problems postsecondary students face. But nothing focuses these statements or pulls them together. Meanwhile, point 3 probably doesn’t belong.

Strategy 1: Group and Sequence Ideas

To solve this problem, separate out ideas into larger topics, put them in logical order, and directly identify the topics for your reader:

1 Students face many pressures today. They are greatly in debt. In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Credentials are no longer enough for employment.

2 There have been attempts to address the issue. Postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life.

Here we’ve

- created two separate topics;

- put them in a logical order (problem → solution); and

- identified each with a topic sentence (1, 2).

By default, topic sentences should go at or near the start of a given paragraph. It’s also possible to put a topic sentence at the end:

Students are greatly in debt. In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Credentials are no longer enough for employment. Students face many pressures today.

Strategy 2: Connect Ideas

Grouping and sequencing help, but the ideas still feel disjointed. We need to link them more with connectives. Connectives are those little words that link, or connect, ideas together:

- Also

- Moreover

- For example, for instance

- Yet

- But

- However

- More importantly/most importantly

- In short

These connectives help you add ideas, contrast two or more ideas by showing difference, summarize, and so on. By using them, you show your readers these same logical connections. Your writing feels more cohesive as a result.

Sometimes punctuation can help in the same way. For example:

- A colon (:) often shows that an example follows.

- An em-dash (—) can be used to emphasize or add an idea—just as this one does.

Students face many pressures today. For example, they are greatly in debt. They’re also stretched thin: In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Worse, the credentials they’re earning are no longer enough for employment.

There have been attempts to address the issue. For instance, postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life.

The words and phrases “for example,” “also,” and “worse,” and the colon (“stretched thin:”) all link ideas together and show the relationships between them. Let’s look at what each connective is doing:

- “For example” connects the subsequent idea to the previous one as an instance or illustration.

- “Also” adds a new, equal idea onto the previous one. (In fact, the entire clause “They’re also stretched thin” is one big connective, showing the relationship between student debt and student overwhelm.)

- The colon (:) after the word “thin” shows that an example or piece of evidence is coming.