Prepare, Pause, and Frame

Get ready to focus and respectfully absorb as you prepare to develop a deep understanding of a source. Initiate connection and spark curiosity.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why engage actively

- How to prepare

- Why pause judgment

- How to quick check

Consider this: According to Internet Live Stats (2020), a site that tracks internet activity, in an average second:

Think about this: How does this volume of information impact our ability to focus, pay attention, and engage with a source long enough to get a deep understanding of it?

Engage Actively

Engaging actively with a source requires focus and attention. It involves creating space in your mind and your day to dive deeply into a source’s content and its message. It requires exploring the message’s nuances, creating connections to what you already know, and appreciating its context.

Passive and active engagement with a source look different. Active engagement takes time and effort, while passive engagement is faster and less focused. As professionals and students, it will be important to decide when active engagement is required.

How Are Active and Passive Engagement Different?

| ACTIVE ENGAGEMENT | PASSIVE ENGAGEMENT |

|---|---|

| Explore the context for the source. | Ignore the context. |

| Examine the purpose. | Engage without purpose. |

| Alter your speed based on the significance and difficulty of the source. | Use the same speed for all sources. |

| Preview before engaging. | Don’t preview; just jump right in. |

| Engage with questions in mind. | Engage without questions in mind. |

| Stop to monitor your understanding. | Don’t stop to think about whether you are understanding. |

| Annotate if reading; read with a pencil or highlighter in hand to mark important passages and jot down notes. | Don’t annotate. Don’t have anything in hand. |

| Make time to reflect upon and evaluate the source. | Don’t make time to reflect upon and evaluate the source. |

Prepare

This first step of engaging actively is about knowing yourself as a reader and finding a space that works for you, away from distractions. If possible, this space should also be a comfortable working environment. Physical discomfort can also interfere with your ability to focus.

For example, you might know that if you sit in a common area, you will be distracted by your roommates and their actions, getting side-tracked and involved in their activities rather than focusing on the source. Or having your phone at your fingertips with alerts buzzing and beeping will lure you onto social media and its enticing diversions.

Along with finding a good physical space, you should also give some thought to the time of day, and your fatigue and energy levels. You probably have a window of time in the day that is most productive for you. Perhaps it’s first thing in the morning when you’re the only one up and your place is quiet. Find that time and use it for tasks that require focus and attention. Put away distractions and set a timer; be prepared to focus for a planned amount of time.

According to an article titled “8 Ways to Improve Your Focus” on fastcompany.com, “If it’s too hot or too cool in your work environment, it could impact your focus. A study from Cornell University found that workers are most productive and make fewer errors in an environment that is somewhere between 68 and 77 degrees [20 and 25 degrees Celsius]. Another study from the Helsinki University of Technology in Finland says the magic temperature is 71 degrees [22 degrees Celsius]. If you don’t control the thermostat, you can opt to bring a sweater or a fan” (Vozza, 2015, para. 12).

Pause Judgment

In our polarized world where people have strong positions on many topics, it can be easy to get caught up in offering opinions. You may navigate frequently through social media, posting and commenting, perhaps positively, perhaps negatively, since, in the digital world, opinions flow quickly and easily. The anonymity and protection of a screen contribute to this.

It is important at times, and especially for professional or academic purposes, to pause. Pause so that you can give quiet and respectful consideration to others’ viewpoints. Pause so that you can develop your own considered, evidence-based response that builds from your understanding, finds common ground, and, when relevant, disagrees constructively.

In this first stage of absorbing a source, you should practise pausing. Wait to hear and understand. Later, you will respond, analyze, and critique.

Quick Check

Ok, now that you’re comfortable, ready to focus, and have paused judgment, you should do one more thing before you start to work with a source: a quick check to frame it. This creates context for understanding and further investigation later. Be inquisitive about the source. Learn a little about it—who is the author? When was it written? Where was it published? What can we predict and learn from the title? This is a time when you might be reminded of how much you love your smartphone because all these answers are at your fingertips. Don’t spend too long on this; a quick internet search should be enough.

QUICK CHECK:

“It’s Time for ‘They.’” Read it here.

Publication Name and Details

“It’s Time for ‘They’” was published in The New York Times. If you don’t know anything about The New York Times as a publication, you could take another few moments to learn more. You’ll learn that it’s an American publication. On first glance, does it seem to be a credible source? Why or why not? These are the sorts of questions you might want to consider quickly, but you will return to explore them further later.

Publication Date

“It’s Time for ‘They’” was published in 2019.

Prediction from Title

The title of this article seems fairly clear. You might expect to read about the word “they,” and given the use of “It’s Time for…,” you might predict that the author is expressing a strongly held opinion in this article.

Author Details

You can also do a quick internet search on the author, Farhad Manjoo. You’ll learn that they have been a columnist at The New York Times since 2018. What else? They were born in South Africa and have been a journalist at other publications since 2008.

Publication Name and Details

What do you know about TED Talks and the organization behind them? There is a ton of information about this platform readily available on the internet, but perhaps the best spot to learn more is at https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization. Here you’ll find that “TED is a nonprofit devoted to spreading ideas, usually in the form of short, powerful talks (18 minutes or less). TED began in 1984 as a conference where Technology, Entertainment and Design converged, and today covers almost all topics—from science to business to global issues—in more than 100 languages” (TED, n.d., para. 1).

Publication Date

“The Danger of a Single Story” was published in 2009.

Prediction from Title

What can you predict from this title? By looking at the wording, you may guess that the source is about “single stories” and that the author thinks these are dangerous. You may guess, correctly, that you’ll hear or read about why the author has this perspective.

Author Details

Onto the author. Her name is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. She has a website—https://www.chimamanda.com/about-chimamanda—that you can access to learn that she is a novelist who grew up in Nigeria. She has won numerous awards. Her TED Talk is one of the most viewed of all time. (As of June 2020, it had been viewed 22 million times.)

A quick check should take you no more than 3–5 minutes. Don’t spend more time on it. The benefit of framing a source is that you’ve begun your journey of engaging with the source, becoming curious about what you will read, and building respectful understanding.

Try It!

Do Your Own Quick Check

Directions:

- Complete a quick check for “Forgiveness Story” by June Callwood in the table provided. Access “Forgiveness Story” here.

- Compare your quick check to the model.

| Title | |

| Publication Name and Details | |

| Publication Date | |

| Prediction from Title | |

| Author Details |

| Title | Quick Check – “Forgiveness Story” |

| Publication Name and Details | • Published in Canadian magazine The Walrus • “The Walrus provokes new thinking and sparks conversation on matters vital to Canadians. As a registered charity, we publish independent, fact-based journalism, produce national, ideas-focused events, and train emerging professionals in publishing and non-profit management. The Walrus is invested in the idea that a healthy society relies on informed citizens” (The Walrus, n.d.) |

| Publication Date | June 12, 2007 |

| Prediction from Title | • Article that focuses on the topic of forgiveness • Not clear if it’s about the author’s opinion on the topic or has a different focus, but expect to read stories of forgiveness |

| Author Details | • Google search lists numerous sites for details on June Callwood • According to cbc.ca, she was a journalist and activist; she was described as “Canada’s Conscience”; she passed away at the age of 82 in April 2007 after a battle with cancer, two months before the publication of “Forgiveness Story” (CBC, n.d.) |

In this subtopic, you’ve learned the first steps of actively engaging with a source including how to

- prepare to engage with a source;

- pause judgment to allow understanding; and

- quick check a source’s background.

Active vs. passive reading. (n.d.). Excelsior Online Reading Lab. https://owl.excelsior.edu/orc/introduction/active-reading

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

Adichie, C. N. (2020, May 18). The danger of a single story. LibreTexts. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Literature_and_Literacy/Book%3A_88_Open_Essays_-_A_Reader_for_Students_of_Composition_and_Rhetoric_(Wangler_and_Ulrich)/Open_Essays/01%3A_The_Danger_of_a_Single_Story_(Adichie)

Callwood, J. (2007, June 12). Forgiveness story. The Walrus. https://thewalrus.ca/forgiveness-story/

CBC. (n.d.). June Callwood: Canada’s conscience. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/topic/june-callwood-canadas-conscience

Internet Live Stats. (2020, June 17). 1 second. Retrieved June 17, 2020, from https://www.internetlivestats.com/one-second/#tweets-band

Manjoo, F. (2019, July 10). It’s time for ‘they.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/pronoun-they-gender.html

TED. (n.d.). Our organization. https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization

The Walrus. (n.d.). The Walrus is Canada’s conversation. https://thewalrus.ca/about/

Vozza, S. (2015, August 8). 8 ways to improve your focus. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/3050123/8-ways-to-improve-your-focus

Skim, Scan, and Use Tools

Get an overview of a source. Find specific content. Proceed to engage closely and focus strategically.

What You’ll Learn:

- How to quick read: skim and scan

- How to use tools to engage closely

Recall what you know: Skimming, scanning, and reading closely are all strategies for engaging with a source. How are they different? Recall what you already know about these strategies by placing the descriptors below in the correct column.

Think about this: Before beginning to engage actively with a source, set a goal. What are you trying to achieve? How much time will you spend? What are the outcomes you are looking for? With this purpose in mind, you can choose how to interact with the source.

Quick Read: Skim and Scan

Skim First

When you skim a source, you go through it quickly so that you begin to grasp its focus, style, and content. The key word here is “quickly.” Remember that a full understanding will come later.

You’ll probably find that you’re adept at looking at content this way; it’s often how we approach the endless stream of media feeds on our devices.

You will engage with countless sources as part of your academic, personal, and professional experience. Your approach to skimming should vary by the type of source, its complexity, its length, and your reason for skimming. Are you skimming before doing a more detailed review of the source? Are you skimming so that you can decide if the source should be used for another purpose—e.g., as support for an argumentative essay you are writing? Are you using skimming to remind yourself of the key parts of a source you read a week ago?

The key is this: Don’t get bogged down when skimming. Focus on only the main points, headings, subheadings, and bolded or highlighted terms. It can be helpful to set a timer to limit how long you spend on this.

Approach to Skimming

Here are three examples of how the time and approach may vary by type of source:

| TYPE OF SOURCE | TIME FOR SKIMMING (approximate) | APPROACH TO SKIMMING |

|---|---|---|

|

Popular: Web Article or Web Page | 1–2 minutes | • Read the title. • Read the first sentences and the last sentences. • Quickly look through the rest of the article to identify keywords and concepts. • Focus on bolded, bulleted, or highlighted content. |

|

Scholarly: Journal Article | 3–4 minutes | • Look at the title, date of publication, and list of authors. • Quickly read the abstract and highlights (if included). • Look at keywords. • Look at headings, subheading, and figures. • Move to the discussion and conclusion, focus in on key findings. |

|

Academic: Textbook Chapter | 5–10 minutes | • Read the chapter title, introduction, and summary. • Look at titles and subtitles. • Focus on figures—charts, tables, images. • Look for definitions. |

Regardless of the source type, the goal of skimming is consistent: You are aiming for a general overview. You should also get a sense of how the source is organized, what the focus is, and keywords or concepts. You may also begin to identify areas that seem most challenging to you as a reader.

Scan with a Purpose

Scanning is also a quick-reading strategy, but when you scan, you’re on a mission. Scanning is not about understanding or absorbing a source as a whole. You are looking for specific content and only that content. You go through the source quickly until you find it, using your time efficiently to achieve your purpose. You could use scanning to

- look up definitions;

- find details such as a client name, technical term, a step in a procedure or experiment;

- search for content to use in a quotation;

- find the answer to a question; or

- locate statistics or data.

Approach to Scanning

- Identify the content you are looking for.

- Scan quickly to find it within the source.

- Stop when you find it.

- Pay close attention to the desired content and the details around it, extracting the required information.

- Move on.

Anatomy and Physiology is an OpenStax book published in 2013. You can access it here.

Approach to Scanning

| APPROACH TO SCANNING | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|

| 1. Identify the content you are looking for. | You have to find the definition of “serous membrane,” an anatomical term. |

| 2. Skim quickly to find it within the source. | You are looking through chapter 1 of Anatomy and Physiology, an open, digital textbook. |

| 3. Stop when you find it. | You find the definition in this part of the source: 1.6. Anatomical Terminology, so you stop here. |

| 4. Pay close attention to the desired content and the details around it, extracting the required information. | You find the definition is this: “A serous membrane (also referred to as a serosa) is one of the thin membranes that cover the walls and organs in the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities” (OpenStax, 2013, “Anatomical Terminology,” para. 13). You capture the definition and citation details. |

| 5. Move on. | You move on to scan for another definition and, in doing so, repeat this process. |

Engage Actively: Use Tools

To absorb a source, you will need to engage closely with it. This requires slow, focused attention on the whole source, but also on its parts. In this section, we will focus on tools that you can use to help you engage closely before moving on to work with the source in other ways (see Situate; Break Down a Source; Summarize; Paraphrase; Clarify, Respond, and Infer). There are numerous proven approaches and tools that can help you immerse your attention and focus on a source.

Annotate

One tool that can help with engaging actively is annotation.

When you annotate, you add comments, notes, and symbols. You might highlight or underline. You work right on the source, not on a separate screen or piece of paper. This means that the annotations become part of the source; this is the power of annotation.

Annotating has a number of benefits:

- It helps you sustain focus and attention on the source.

- It assists you in making personal connections with the source.

- It reminds you to look further if you encounter content, terms, or ideas in the source that you find challenging or are new to you (e.g. look up the definition of a new word).

- It creates a personalized record of your interaction with a source that you can refer back to at a later date.

- With digital annotation tools, you can collaborate and connect with others as you annotate.

Annotating should be personal in nature; over time, you will develop your own approach to annotating that makes sense. Perhaps you will use colour coding or develop a set of symbols, or a combination of both.

Research on Reading Strategies

Did you know? The effectiveness of reading strategies is supported by research.

As discussed in a study published in Educational Technology & Society, “Many studies have found reading strategies useful when implemented before, during or after reading (e.g., Brown, 2002; Ediger, 2005; Fagan, 2003; McGlinchey & Hixson, 2004; Millis & King, 2001; Sorrell, 1996). For example, reading strategies include rereading, scanning, summarizing, keywords, context clues, question-answer relationships, inferring, thinking aloud, activating prior knowledge, setting a purpose, and drawing conclusions” (Hsieh & Dwyer, 2009, p. 36).

A 2018 study published by TESL Canada Journal also discusses the importance of reading strategies: “Studies have shown that reading improves a reader’s vocabulary, grammar, and reading comprehension, and that using strategies when reading leads to improved reading comprehension (Anderson, 1991; Grabe & Stoller, 2011; Hudson, 2007; Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2008)” (Khatari, 2018, p. 80).

Further, a 2008 study published in Issues in Educational Research comments on the role of reading strategies in cognitive processing: “Successful comprehension does not occur automatically. Rather, successful comprehension depends on directed cognitive effort, referred to as metacognitive processing, which consists of knowledge about and regulation of cognitive processing. During reading, metacognitive processing is expressed through strategies, which are ‘procedural, purposeful, effortful, willful, essential, and facilitative in nature’ and ‘the reader must purposefully or intentionally or willfully invoke strategies’ (Alexander & Jetton, 2000, p. 295), and does so to regulate and enhance learning from text” (Cubukcu, 2008, p. 3).

Here are two examples of annotation systems that could work for you:

| AREA OF SOURCE | COLOUR CODING | LABELS AND SYMBOLS |

|---|---|---|

| Main idea/thesis | Highlight in yellow | Underline |

| New word, important term | Highlight in blue | Circle |

| Key supporting point, statistic, other evidence | Highlight in green | Emphasize with an exclamation mark |

| Challenging or confusing content to be revisited or explored further | Highlight in red | Place a star beside/around content |

| Questions, responses, or commentary you have as you engage with the source | Write beside area of source that sparked the question, response, or commentary; write in the margin or around the content; use physical or digital sticky notes | |

Many sources today are digital. Digital media can be annotated with annotation apps, and, subsequently, the annotation can be saved, printed, and/or shared. Digital annotation can be public and collaborative, allowing for conversations on the text. Comments can be added through voice recordings in some applications. Many digital annotation tools can be used in different ways. Here is a beginning list:

(Note: Authors are not endorsed by these companies, and students should use at their own risk.)

More details on these digital tools can be found here:

- “Annotating Text, Images, and Videos Online” by Stanford University

- “Top Tech for Digital Annotation” by Common Sense Education

Reverse Outlines

You’ve likely used outlines to select, develop, and organize your ideas as part of the writing process. A reverse outline, as its name suggests, works in reverse. You take a published source and produce an outline from it. This can also be an effective first step in summarizing a source.

When creating a reverse outline, it can be helpful to use a table with two columns: one for the location information (e.g. paragraph number), and the other for the summary of that part of the source. When summarizing a paragraph, try to keep it to one to two sentences in length.

Here is an example of a reverse outline of the first segment of “You’ve Got to Find What You Love” by Steve Jobs; it focuses on paragraphs 1 to 9 of the speech.

| LOCATION | SUMMARY |

|---|---|

| para. 1 | honoured to give the speech, will focus on three stories |

| para. 2 | first story: connecting the dots |

| para. 3 | dropped out of college after six months |

| para. 4 | adopted at birth; his birth mother ensured that adoptive parents would send him to college |

| para. 5–6 | went to college but dropped out after six months; was not engaged in his program, started auditing other classes |

| para. 7 | one class he audited, calligraphy, had an impact; he learned about typography |

| para. 8 | years later, used knowledge of typography when designing the Mac; this became the norm for personal computers and would not have happened if he had stayed in original college program |

| para. 9 | connecting the dots between life events can only be done with hindsight, have to trust that there is a purpose to choices |

Other Tools

There are many additional tools that can help you actively engage with a source.

Graphic Organizers: Graphic organizers area visual representation of a concept, an idea, or information. They are used for various purposes and can be as simple as a table or as elaborate as a mind map with many connections. They are particularly effective for visual learners. You can find a description of graphic organizers, as well as templates and examples here.

Journals: Like annotations, journals can be physical or digital. They are useful for developing a permanent archive of ideas, connections, and questions related to sources. They can also be used to capture quotations and specific content such as data or statistics from sources that can be used in your writing. Examples of specific types of journals are provided in the book Reading Reconsidered; the authors, Lemov, Driggs and Woolway (2016), recommend the following journals: double-entry quotation journals, common-place journals, essential question trackers, hypothesis trackers, and theme or motif trackers (pp. 334–335).

Lemov, D., Driggs, C., & Woolway, E. (2016). Reading reconsidered: A practical guide to rigorous literacy instruction. Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley.

Text-to-Talk: If you are an auditory learner—someone who learns well by listening—your understanding will increase if you listen to a source. This can be used to accompany your reading. You can try out a free, easy-to-use, and versatile text-to-talk online tool called NaturalReader here.

SQ3R: This is a reading strategy that prescribes five steps in the reading process: 1) survey (skim the source); 2) question (identify questions); 3) read (go through the source thoroughly); 4) recite/recall (assess your ability to recite or recall what you have learned); and 5) review (refresh and ensure understanding through review at a later date) (Lumen, n.d., Chapter 12, para. 23–25). You can read more about this strategy here.

Active Reading Documents: This reading strategy involves capturing your understanding of a source and making logical connections between the source and other sources. This can work well for program-related content and assigned textbook readings. Like SQ3R, there are five tasks: 1) create visual representations of information; 2) depict personal understanding with short explanations and/or visual representations; 3) identify and explain logical connections within the reading; 4) identify and explain logical connections to other chapters or units; and 5) identify and explain logical connections to related academic content and to personal, social, or professional aspects of life (Dubas & Toledo, 2015, p. 29). You can read more here.

Self-Explanation Reading Training: Self-Explanation Reading Training (SERT) is “designed to improve students’ ability to generate effective inferences while reading complex text. Self-explanation refers to the process of explaining aloud the meaning of written text to oneself” (McNamara, 2017, p. 480). As the name suggests, when using SERT, you explain a source’s content to yourself, checking on your own understanding as you go. This involves a combination of comprehension monitoring, paraphrasing, elaboration, and using logic, predicting, and inferring (McNamara, 2017, p. 481). You can read more here.

Try It!

Directions:

- Practise creating a reverse outline of section 2 (para. 10–15) of “You’ve Got to Find What You Love” by Steve Jobs. Use the outline template below.

- Compare your reverse outline with the model.

| para. 10 | |

| para. 11 | |

| para. 12 | |

| para. 13 | |

| para. 14 | |

| para. 15 |

| para. 10 | second story: love and loss |

| para. 11 | co-founded and grew Apple to large company in ten years; got fired from Apple at the age of 30 |

| para. 12 | felt distraught, embarrassed that events occurred in public eye, but decided to begin again, still passionate and motivated |

| para. 13 | realized that separation from Apple was liberating, allowed more innovation |

| para. 14 | started NeXT, Pixar, met wife, Apple bought NeXT, went back to work at Apple; innovation from NeXT was instrumental at Apple |

| para. 15 | don’t compromise or give up on vision and goals despite hitting roadblocks; loving what you do will lead to outstanding results |

In this subtopic, you have covered how to

- get a general understanding of a source by skimming;

- find specific content in a source by scanning; and

- use annotation, reverse outlining, and various other tools to engage closely.

Freedman, L. (n.d.). Skimming and scanning. University of Toronto. https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/skim-and-scan/

GradProSkills. (2017, September 21). Reading strategies: Skimming vs close reading [Blog post]. Concordia University. https://www.concordia.ca/cunews/offices/vprgs/gradproskills/blogs/2017/09/21/reading-strategies-skimming-vs-close-reading.html

How to annotate. (n.d.). English Composition 1. Lumen Learning. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/engcomp1-wmopen/chapter/text-how-to-annotate/

Skimming and scanning. (n.d.). Butte University. http://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/readingstrategies/skimming_scanning.html

Active reading strategies. (n.d.). EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies. Lumen Learning. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/austincc-learningframeworks/chapter/chapter-12-active-reading-strategies/

Common Sense Education. (n.d.). Top tech for digital annotation. https://www.commonsense.org/education/top-picks/top-tech-for-digital-annotation

Cubukcu, F. (2008). Enhancing vocabulary development and reading comprehension through metacognitive strategies. Issues in Educational Research, 18(1), 1–11. http://ra.ocls.ca/ra/login.aspx?inst=centennial&url=https://search-proquest-com.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/docview/2393126912?accountid=39331

Dubas, J. M., & Toledo, S. A. (2015). Active reading documents (ARDs): A tool to facilitate meaningful learning through reading. College Teaching, 63(1), 27–33. doi:10.1080/87567555.2014.972319

Education Bureau. (n.d.). The use of graphic organizers to enhance thinking skills in the learning of economics. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/pshe/references-and-resources/economics/use_of_graphic_organizers.pdf

Hsieh, P., & Dwyer, F. (2009). The instructional effect of online reading strategies and learning styles on student academic achievement. Educational Technology & Society, 12(2), 36–50.

Jobs, S. (2005, June 14). ‘You’ve got to find what you love,’ Jobs says. Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/14/jobs-061505/

Khatri, R. (2018). The efficacy of academic reading strategy instruction among adult English as an additional language students: A professional development opportunity through action research. TESL Canada Journal, 35(2), 78+. https://link-gale-com.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/apps/doc/A582623251/CPI?u=ko_acd_cec&sid=CPI&xid=25036bcb

Lemov, D., Driggs, C., & Woolway, E. (2016). Reading reconsidered: A practical guide to rigorous literacy instruction. Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley.

Levy, S. (2020, October 1). Steve Jobs. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Steve-Jobs

McNamara, D. (2017). Self-explanation and reading strategy training (SERT) improves low-knowledge students’ science course performance. Discourse Processes, 54(7), 479–492. https://doi-org.ezcentennial.ocls.ca/10.1080/0163853X.2015.1101328

NaturalReader. (n.d.). https://www.naturalreaders.com/online/

OpenStax. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology

Stanford. (2008, March 7). Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford commencement address [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UF8uR6Z6KLc

Stanford University. (2020). Annotating text, images, and videos online.

Situate

Explore the situation surrounding a source. Gain further insight by identifying its subject, genre, audience, purpose, and setting.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why situate a source

- How to situate a source

Consider this: Society changes over time. These changes make the views of earlier generations outdated, only relevant in the context of their time and place in history.

Review the statements below. Which Canadian societal change makes the views in these statements outdated? Find the correct match.

Think about this: How does societal context impact an author’s views, opinions, and ways of expressing them? How important is it, when absorbing a source, to understand this context?

Why Situate

If you’ve already prepared and done a quick check (see Prepare, Pause, and Frame), you have a sense of the author’s background and know a little about when and where the source was published. This is an important first step. Now you’re ready to dig deeper into the source.

You should start by situating it, or placing it in a rhetorical context.

For example, imagine you are a student in 2040, reading an article written in 2020. To understand this article further, it would help to know more about the key contexts of the time. You’d find that the world in 2020 was in the midst of a global pandemic. This would help you understand the author’s choices and mindset at the time of writing the piece. It would also give insight into the outlook and attitude of its intended audience.

Or, perhaps, you’re reading a newspaper article in which an author expresses an opinion about fear of missing out (FOMO). The article was written in 2011. When you research further, you learn that iPhones were introduced in 2007, and social media platforms became more popular during the years after this. While the impact of social media is well known today, you find that the concerns of the author are insightful given its date of publication. You also gain a greater understanding of the observations and experiences shared by the author.

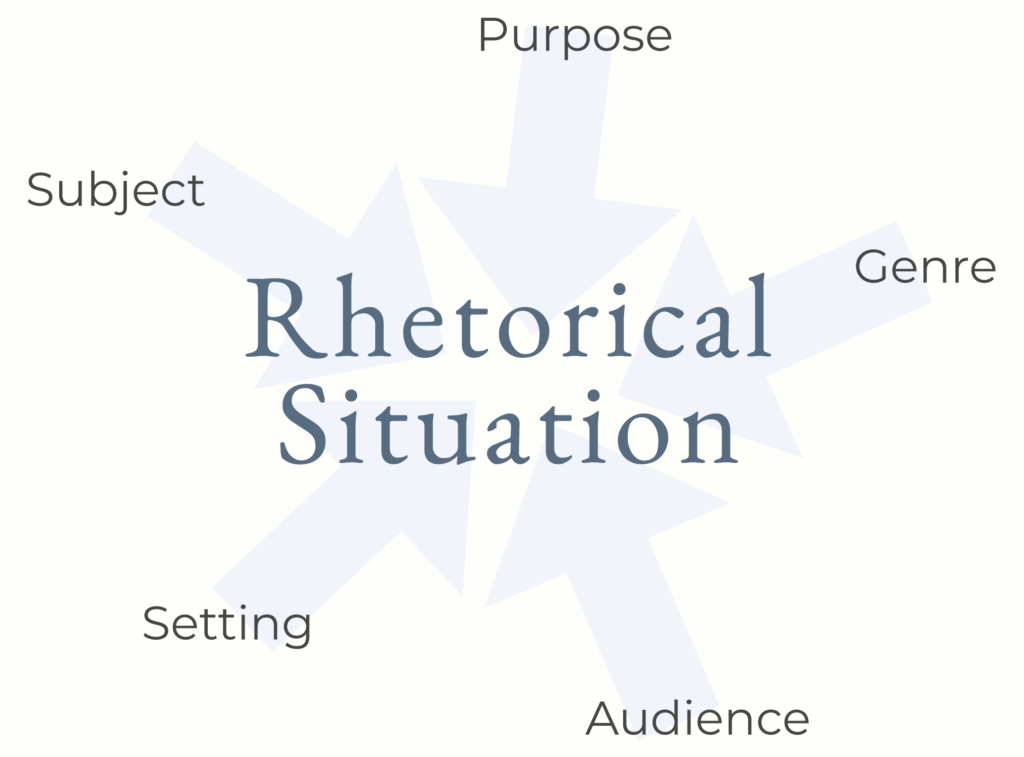

How to Situate

To situate a source, you should examine five elements: subject, genre, audience, purpose, and setting. By doing this, you consider why the source exists and determine how contextual factors led to its development and content.

Three sources are used as examples for “Rhetorical Context Defined.”

“Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Postsecondary Students” is a report from Statistics Canada published in May 2020. It is based on data collected from and about Canada and/or Canadians. You can find out more about Statistics Canada here.

“Pandemics Aren’t Wars” was published by Vox in April 2020 and was written by Alissa Wilkinson. Vox is a free online American publication that explains the news. You can find out more about the publication here.

“Most Common Panic-Buying Purchases During Coronavirus” was published by The Onion in May 2020. The Onion is an American satirical online publication that focuses on global and local news topics. You can learn more about the publication here.

| RHETORICAL | RHETORICAL CONTEXT DEFINED | |

|---|---|---|

| Subject | What is the topic of the source? | The subject should be captured in a specific short phrase. For example, in the case of the three sources listed above, the subjects would be “Impacts of COVID-19” (Statistics Canada report), “COVID-19 Compared to War” (Vox article by Alissa Wilkinson), or “COVID-19 and Purchasing Behaviour” (The Onion article). |

| Genre | What is the type of source? | There are many categories for both fiction and non-fiction. Non-fiction sources, the type most relevant to college students, include reports, essays, textbooks, reference books, biographies, and personal narratives. |

| Purpose | What was the author’s purpose in creating the source? | Generally, the purpose is described in one of three ways: to inform (e.g. the Statistics Canada report “Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Postsecondary Students”), to persuade (e.g. the opinion piece on Vox “Pandemics Aren’t Wars”), or to entertain (e.g. the satirical article published by The Onion “Most Common Panic-Buying Purchases During Coronavirus”). |

| Audience | Who are the intended readers or viewers of the source? | To determine the intended audience, you should look at: 1) the publication and its intended audience; and 2) the language used by the author—is it specialized (e.g. jargon for a specific professional audience), complex, formal, or informal? |

| Setting | What was happening—culturally, politically, socially—that may have influenced the author? | This requires a scan of factors that may have motivated the author. In all the above examples, the authors were influenced by the global COVID-19 pandemic and its extensive impact on day-to-day life. |

How Does Audience Influence Language?

As a communicator, you make choices about language all the time, and many of these choices depend on your audience.

Imagine this: You will miss class due to a doctor’s appointment and are concerned about getting caught up on the materials.

You text your friend this message:

hey im not going to be in class due to drs appt can you send pic of notes ttul

You email your professor this message:

Dear Prof. Gupta, Unfortunately, due to a medical appointment, I will have to miss your class today. If possible, could you post your notes so that I can review them tonight? Thank you, Sophie

Think about this: Although the purpose of these messages is similar—to advise someone that you are missing class and to make a request about class notes—the language choices are quite different. The personal message to a friend is written in informal language with short forms of words and no punctuation. The message to a professor is more formal, using correct sentence form.

All authors make intentional language choices when they consider their audience and purpose.

In the following example, we will explore the rhetorical context of a source.

Watch this: “The Amazon Belongs to Humanity—Let’s Protect It Together”

Now, learn more about this source in two steps:

Step 1: Do a quick check—find the author(s), publication, and publication date.

The quick check should be really fast. In less than a minute, you can find these details:

Authors – Tashka and Laura Yawanawá. Learn more here

Publication –Ted.com. Learn more here

Publication Date – September 2019

Step 2: Investigate the rhetorical situation.

When you have watched the video and done a little more searching, you’ll be able to identify its rhetorical situation:

Subject – protection of the Amazon

Genre – non-fiction, speech

Audience – viewers of TED Talks, general public since language is straightforward with no technical terms or jargon

Purpose – to persuade viewers that Indigenous people need to be heard; they have the answers to protecting the Amazon

Setting –

• “Indigenous peoples inhabit a large portion of the Amazon rainforest and their traditional and cultural beliefs have existed for centuries” (Lutz, n.d., para. 1)—read here

• in Brazil, 160 societies live within the Amazon (Lutz, n.d., para. 2)

one of the presenters, Tashka Yawanawá, is the chief of the Yawanawá people: “he leads 900 people stewarding 400,000 acres of Amazon rainforest in Brazil” (Skoll, n.d., para. 1)

• the threat to the Brazilian Amazon rainforest increased in January 2019 when Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, “cut funds for the enforcement of Brazil’s strict environmental laws, leading Amazon deforestation to spike” (EcoWatch, 2020, para. 14)

• the video was published at a time of significant increase in forest fires in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest; “There were … 19,925 fire outbreaks in September [2019] in the Brazilian part of the rainforest … the numbers soared by 41% compared to the same period in 2018” (Ortiz, 2019, para. 5)

When you are familiar with a source’s rhetorical context, you can situate it within the bigger picture, and are able to appreciate the source, its perspective, and its role, leading to greater understanding. You will later be able to analyze and critique it.

Try It!

Directions:

- Practise identifying rhetorical context for “It’s Time for ‘They’” and “You’ve Got to Find What You Love” by placing the following descriptors in the correct spot in the Rhetorical Context Chart.

- Compare your rhetorical context to the model.

“It’s Time for ‘They’” by Farhad Manjoo is a 2019 article from The New York Times. Read it here, find more about the author here, and learn about The New York Times here.

“You’ve Got to Find What You Love” by Steve Jobs is a 2005 commencement speech made at Stanford University. Read it here, watch it here, and find more about the author here.

In this subtopic, you’ve learned

- why it is important to explore the rhetorical context of a source;

- what should be considered as part of a source’s context; and

- how to situate a source.

Canadian Cancer Society. (n.d.). Why tobacco control is important. https://www.cancer.ca/en/get-involved/take-action/what-we-are-doing/tobacco-control/?region=on

CBC. (2013, February 26). Women & the right to vote in Canada: An important clarification. https://www.cbc.ca/strombo/news/women-the-right-to-vote-in-canada-an-important-clarification.html

Ecowatch. (2020, February 28). Indigenous people may be the Amazon’s last hope. https://www.ecowatch.com/indigenous-people-amazon-2645327056.html?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1

Government of Canada. (2007, February 5). History of Canada’s food guides from 1942 to 2007. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-food-guide/about/history-food-guide.html

Government of Canada. (2020, July 24). Medical assistance in dying. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying.html

Hardcastle, L. (2018, December 3). Decriminalization of cannabis and Canadian youth. University of Calgary Faculty of Law. https://ablawg.ca/2018/12/03/decriminalization-of-cannabis-and-canadian-youth/

Jobs, S. (2005, June 14). ‘You’ve got to find what you love,’ Jobs says. Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/14/jobs-061505/

Kirkey, S. (2019, January 22). Got milk? Not so much. Health Canada’s new food guide drops ‘milk and alternatives’ and favours plant-based protein. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/health/health-canada-new-food-guide-2019

Koren, M. (2019, July 11). Why men thought women weren’t made to vote. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/07/womens-suffrage-nineteenth-amendment-pseudoscience/593710/

Levy, S. (2020, October 1). Steve Jobs. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Steve-Jobs

Little, B. (2018, September 13). When cigarette companies used doctors to push smoking. History. https://www.history.com/news/cigarette-ads-doctors-smoking-endorsement

Logan, R. (2001, July). Crime statistics in Canada, 2002. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/85-002-x2001008-eng.pdf?st=ge9X09Hj

Lutz, D. (n.d.). Indigenous people. Amazon Aid Foundation. https://amazonaid.org/indigenous-people/

Manjoo, F. (2019, July 10). It’s time for ‘they.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/pronoun-they-gender.html

Marshall, T. (2016). Assisted suicide in Canada. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 28, 2020, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/assisted-suicide-in-canada

Martin, V. (n.d.). Meet Tashka and Laura Yawanawa. Sanctuary Nature Foundation. https://www.sanctuarynaturefoundation.org/article/meet-tashka-and-laura-yawanawa

Oritz, J. (2019, October 18). The Amazon hasn’t stopped burning. There were 19,925 fire outbreaks last month, and ‘more fires’ are in the future. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/10/18/amazon-rainforest-still-burning-more-fires-future/4011238002/

Skoll. (n.d.). Biography: Tashka Yawanawa. https://skoll.org/contributor/tashka-yawanawa/

Stanford. (2008, March 7). Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford commencement address [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UF8uR6Z6KLc

Statistics Canada. (n.d.). https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start

Statistics Canada. (2020, May 12). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on postsecondary students. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200512/dq200512a-eng.htmStatistics Canada. (n.d.). https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start

TED. (n.d.). Our organization. https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization

The New York Times Company. (n.d.). Company. https://www.nytco.com/company/

The New York Times. (n.d.). Farhad Manjoo. https://www.nytimes.com/by/farhad-manjoo

The Onion. (n.d.). About The Onion. https://www.theonion.com/about

The Onion. (2020, May 8). Most common panic-buying purchases curing coronavirus. https://www.theonion.com/most-common-panic-buying-purchases-during-coronavirus-1843345581

Vox. (n.d.). About us. https://www.vox.com/pages/about-us

Wilkinson, A. (2020, April 15). Pandemics are not wars. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/2020/4/15/21193679/coronavirus-pandemic-war-metaphor-ecology-microbiome

Yawanawá, T., & Yawanawá, L. (2019, September). The Amazon belongs to humanity – let’s protect it together [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/tashka_and_laura_yawanawa_the_amazon_belongs_to_humanity_let_s_protect_it_together/up-next

Break Down a Source

Break down a source to show its meaning is clear to you. Develop a starting point for interpretation, evaluation, and critique.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why break down a source

- What are arguments and personal narratives

- How to break down arguments

- How to break down personal narratives

Pandemic Lessons: An Effective Argument?

Read this: In a May 2020 cbc.ca article, Canadian Mark Sakamoto expresses this view on COVID-19: “This pandemic has highlighted how our globalized and deeply interconnected world can be so vulnerable to a virus. How quickly and widely it can spread—to devastating effect. However, it has also shown us that our knowledge and expertise and hope can be shared just as quickly” (para. 3–4).

Consider this: There is hope to this perspective. Do you share this view? Does it relate to your experiences during the pandemic? What would you want to know before evaluating this argument further? How could you ensure that you assess the argument fairly and respectfully?

Read the full piece here. Read more about the author here.

Why Break Down a Source

When you break down a source, you gain a clearer picture of how it is constructed. The benefits include

- furthering your understanding;

- identifying its parts and its structure; and

- laying the foundation, when applicable, for your development of a similar source, or for evaluation, interpretation, and critique.

For example, perhaps you must write a formal technical report as the culminating task for a capstone course in your program. Your professor provides you with a sample report from a previous student to use as a model. Your professor asks you to take the report apart, noticing its focus, support, organization, and style of writing. In doing this, you begin to understand how the report is constructed and think about how you will apply this understanding to write your formal report.

Or you are presenting an overview and interpretation of a recently released journal article in your field. You need to break down the article into its main idea and supporting points before you can interpret it. As you work on this, you develop a deeper understanding of the source’s position, and subsequently, you can begin to evaluate the strength and credibility of its support (see Rob’s Subtopics).

Arguments and Personal Narratives

(Content in this section is used with permission from Unit 6 of Centennial College 170 Online, Winter 2020.)

We will examine two types of sources further since they are often used in college-level communication courses: arguments and personal narratives. Both offer a perspective on an issue, question, or problem. Both have a message to share and provide support for that message.

However, they are different in several ways.

Arguments typically address a current issue and are persuasive—that is, the author has an opinion on a subject and intends to persuade the audience of their point of view. They do this by using various reasons and forms of evidence to influence the audience and substantiate their main idea or thesis. Their thesis is often directly stated.

Personal narratives address a problem or question and use first-person fact-based experiences, anecdotes, and life details to support the author’s perspective. Their main message is often implied and has to be determined by the audience after careful consideration.

| ARGUMENT | NARRATIVE |

|---|---|

| Addresses an issue | Addresses a problem or question |

| Includes a thesis (often explicitly stated) | Includes a main idea (often implied) |

| Provides reasons to support the thesis | Uses critical events (plot) from a story to emphasize, illustrate, and/or reinforce the main idea |

| Uses various types of evidence to support the thesis | Uses other narrative strategies and elements |

How to: Break Down an Argument

(Content in this section is used with permission from Unit 6 of Centennial College 170 Online, Winter 2020.}

Most arguments contain some mixture of the following types of strategy, known as rhetorical appeals (Centennial College, n.d., para. 5):

Logical: The writer persuades through facts and reasoning designed to seem rational and reasonable.

Emotional: The writer persuades through imagery, words, and stories designed to make the reader feel an emotion—joy, horror, sadness, empathy, etc.

Ethical: The writer persuades through markers of credibility (writing that is fair-minded, accurate, and self-aware; but this may also refer to elements not directly in the text, such as the writer’s background, experience, education, and reputation).

When you take an argument apart, you will look for its issue, thesis, reasons, and evidence.

An issue is the question or controversy addressed by the author.

The thesis is the author’s perspective or point of view about the issue.

- Evidence is provided by the author to support the thesis.

- It helps to explain and provide reasons for the author’s position.

- Evidence can take various forms including anecdotes, personal observations or experiences, expert knowledge, statistics, historical details, scenarios, common knowledge, and analogies.

More on Evidence

| TYPES OF EVIDENCE | EXAMPLES | WHAT YOU’LL SEE |

|---|---|---|

| Stories or accounts based on the author’s personal experience | Stories or accounts based on the author’s personal experience | “I,” “my,” and other uses of the singular first-person voice |

| Expert (or disciplinary) knowledge | Theories, concepts, or research produced by scholars, journalists, scientists, or other writers | Full name of the expert, title of work by expert, university or college affiliation, title (i.e. PhD or Dr.), reference to study/results, such as “recent studies show. . .” |

| Statistics | Research in the form of data | Historical details |

| Historical details | Specific events that take place in the recent or distant past | Dates, places, notable historical figures/events (“9/11,” “WWII,” “Gulf War,” etc.) |

| Scenarios | Hypothetical situations | Asked to imagine a possible situation that could happen |

| Common knowledge | Information that is shared and widely known by the general public; may be extended to include commonly shared experiences and observations | Might use “we,” “our,” and other uses of the plural first-person voice |

| Analogies | Comparisons | Similarities found between two subjects, may use words or phrases such as “like,” “compared to,” “similar to” |

We’ll practise breaking down an argument by looking further at “It’s Time for ‘They’” by Farhad Manjoo.

| Break Down an Argument: “It’s Time for ‘They’” by Farhad Manjoo | |

|---|---|

|

Issue Tip: Express as a question. | Should the plural pronoun ‘they’ be used in place of the singular gendered pronouns ‘he’ and ‘she’ in common usage? |

|

Thesis Tip: Express as an answer to the question. | In 2020, we should make the shift to ‘they,’ avoiding gender assumptions in our choice of pronouns (see para. 5, 6, and 18) |

|

Reasons & Evidence | Few linguistic advantages to gendered pronouns he/she (para. 3) • personal observation (para. 3) “They” is ubiquitous, inclusive, neutral, and already widely used (para. 7) • expert opinion (para. 8–10) “They” is used in mainstream media by marketers and companies • personal observation (para. 11) “They” does not default to the limitations of gender binary • personal observation (para. 13–16) |

When you break down Manjoo’s argument in this way, it is simplified. You can use this simplified version to verify your understanding of the argument with a professor, colleague, or friend. In addition, you may want to find other opinions that respond to the same issue. You can use the issue to develop a research question and look for other relevant sources.

Subsequently, you can assess how well Manjoo supports the thesis with reasons and evidence. Are they sufficient to you as a reader? Would you prefer to see less personal experience and more expert opinion? Perhaps, if you prefer logical appeals—numbers, research studies, expert opinions—you would feel more persuaded if Manjoo increased the use of these forms of evidence.

How to: Break Down a Personal Narrative

(Content in this section is used with permission from Unit 6 of Centennial College 170 Online, Winter 2020.)

Personal narratives are an essay about a particular moment, event, problem, or question that occurs in the author’s life. They are usually brief and tightly focused. They use the same narrative techniques as fictional stories—plot, character, setting, figurative language—but they are true and autobiographical.

When you break down a personal narrative, you should look for its problem, main message, and narrative strategies/elements.

The writer of a personal narrative usually seeks to understand or unravel some specific problem or question in their life.

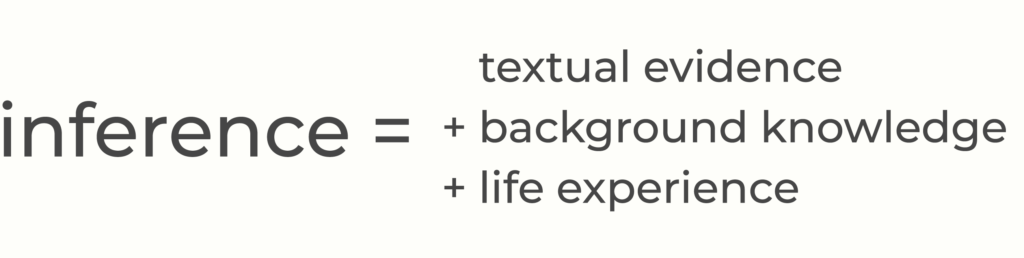

Narrative writers typically avoid stating their main meaning directly. Readers must infer the lesson of the narrative, and it’s possible for different readers to arrive at different—but related—interpretations. As a reader, questions to ask may include “What does the writer most want me to understand?” or “What is the writer’s central insight?”

Narratives are built out of narrative elements, using key events in the personal story to support the main message. Narrative elements include character, plot, setting, theme, and symbolic or figurative language.

We’ll practise breaking down a personal narrative by looking further at “The Danger of a Single Story” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

Break Down a Personal Narrative: “The Danger of a Single Story” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

| Problem/Question Tip: Can be expressed as a question or a statement. | |

|---|---|

|

Problem/Question Tip: Can be expressed as a question or a statement. | Why should people avoid simplifying the narratives of others’ lives? |

|

Main Message Tip: Express as a statement, related to the problem/question. | When viewing others, we should avoid the tendency to simplify someone’s life into a “typical” narrative because it will be incomplete; we will overlook nuances and be influenced by stereotype, bias |

|

Narrative Elements Tip: Address various elements. | Events/Plot

e.g. From paragraphs 1 to 20 only • grew up in Nigeria influenced by British and American literature • recalls a limited view of a neighborhood boy • attends university in America and is viewed by the single story of Africa: “a single story of catastrophe” • visits Mexico and had her own limited view of Mexicans/the country Setting: e.g. Geographical – Nigeria, America, Mexico e.g. Time – 1970s to 2000s (Adichie’s childhood to adulthood) Characters: e.g. Adichie, parents, university roommate, other Nigerians Theme: e.g. Limitations of stereotypes: “What struck me was this: She felt sorry for me even before she saw me…. My roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe” (para. 13). |

When you break down Adichie’s narrative, you get a well-defined picture of it. You clearly identify its main message and how Adichie supports it. Again, it gives you an opportunity to verify your understanding before moving on to evaluate and interpret it. You can also search for other sources that relate to it, that address the same problem. This allows you to begin to evaluate Adichie’s ideas. Are her ideas relevant? Are they shared by others? Are they verifiable? Can you find other authors who support or, perhaps, contradict Adichie’s perspective on this problem?

Try It!

Directions:

A. Break Down an Argument

- Watch “Fighting Islamophobia with Education” by Shafique Virani.

- Break down Virani’s argument by identifying the issue, thesis, and reasons/evidence.

- Check your work with your instructor or a peer.

B. Break Down a Narrative

- Read “Why Would My Father Not Want to Know Me” by Tara Ellison.

- Break down Ellison’s personal narrative by identifying the problem, main message, and narrative elements.

- Check your work with your instructor or a peer.

In this subtopic, you’ve learned an important step in absorbing a source. This includes

- defining arguments and personal narratives;

- breaking down arguments into issue, thesis, and reasons/evidence; and

- breaking down personal narratives into problems, main message, and narrative elements or strategies.

Adichie, C. N. (n.d.). About. https://www.chimamanda.com/about-chimamanda

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

Adichie, C. N. (2020, May 18). The danger of a single story. LibreTexts. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Literature_and_Literacy/Book%3A_88_Open_Essays_-_A_Reader_for_Students_of_Composition_and_Rhetoric_(Wangler_and_Ulrich)/Open_Essays/01%3A_The_Danger_of_a_Single_Story_(Adichie)

CBC. (n.d.). Mark Sakamoto. https://www.cbc.ca/arts/mark-sakamoto-1.4582744

CBC News. (n.d.). About CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/about-cbc-news-1.1294364

CBC News: The National. (2017, April 4). Fighting Islamophobia with education | ViewPoints [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/TtXCJ6NQwSY

Centennial College. (n.d.). Unit 6: Beginning project 2 – choosing a source. In COMM 170. Winter 2020 [Online course]. https://e.centennialcollege.ca/d2l/le/content/496524/viewContent/5529231/View

Ellison, T. (n.d.). About Tara. https://taraellison.com/

Ellison, T. (2020, June 19). Why would my father not want to know me. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/style/modern-love-coronavirus-missing-father.html

Manjoo, F. (2019, July 10). It’s time for ‘they’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/pronoun-they-gender.html

Sakamoto, M. (2020, May 24). Knowledge, expertise and home can spread just as quickly as a virus. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-mark-sakamoto-learning-during-covid-crisis-1.5559452

TED. (n.d.). Our organization. https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization

The New York Times Company. (n.d.). Company. https://www.nytco.com/company/

The New York Times. (n.d.). Farhad Manjoo. https://www.nytimes.com/by/farhad-manjoo

The New York Times. (n.d.). Modern Love. https://www.nytimes.com/column/modern-love

Virani, S. N. (n.d.). About Professor Virani. https://shafiquevirani.org/

Summarize

Create shortened versions of a source in a respectful, neutral, and fair way that reflect a deep understanding.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why summarize

- How to summarize

- How to give attribution

- How to stay neutral

Recall what you know: What do you already know about summarizing? Take this quick true or false test to find out.

Summaries can range in length from a couple of sentences to multiple paragraphs.

The correct answer is

TRUE: depending on the length of the original source that is being summarized and the type of summary you are writing, the length will vary.

Summaries should clearly acknowledge the original source that is being summarized.

The correct answer is

TRUE: it’s important that a summary states the title, author, and date of the original source; typically, it should be identified in the opening of the summary.

Written summaries can use word-for-word content from the original source.

The correct answer is

FALSE: typically summaries should be written in your own words and avoid quoted content from the original source.

Summaries should include your opinion and evaluation.

The correct answer is

FALSE: summaries should be objective and remain neutral.

Summarizing is an important academic skill, but you won’t need to summarize in your professional life.

The correct answer is

FALSE: summarizing is considered an important skill in the workplace. According to Bhavna Dalal (2016) in an article published by Forbes India, “A well-spoken summary can verify that people understand each other. It can make communications more efficient and ensure that the gist of the communication is captured by all involved” (para. 19).

Think about this: Effective summarizing reflects your understanding of a source. Summarizing is simple, but not easy! This is where the time you spend on getting to know a source (see Prepare, Pause, and Frame; Skim, Scan, and Use Tools; Situate; Break Down a Source) will pay off. How effective are your summarizing skills? What can you do to improve them? How can you ensure your summaries have academic integrity?

Why Summarize

When you summarize, you condense and restate the essential meaning of a source. You use your own words but respect the message of the original without adding, interpreting, or assessing anything.

This is key: Your judgment and critical evaluation are on hold, for now.

Think about the areas of your life in which summarizing plays an important role. In an academic setting, some examples of summarizing include

- integrating content from a source into your work to add credibility to yourself as an author and/or to build an argument;

- showing your group members or professors that you grasp their ideas;

- making notes while studying, as you work independently or collaboratively on ensuring that you comprehend course material; and

- capturing findings from a recent journal article.

Beyond this, in academic, professional, or personal contexts, you can use summarizing in active listening, a valuable skill. You can also use it to share ideas, find common ground, identify and correct misunderstandings, and de-escalate conflict.

Imagine This: Summarizing Scenarios

| Scenario | How Summarizing Helps |

|---|---|

| Due to a medical appointment, your group member misses an important three-hour class. This is a problem since you are working on an assignment together that requires an understanding of that class content. Given your busy schedules, you only have one night to work on the assignment, so it’s essential that your group member catches up quickly. | You summarize the class content for your group member, highlighting the main points. You’re able to do this in 30 minutes because you omit activities and the minor points made by the professor. Now, you can move on to complete the assignment effectively. |

| You and a colleague do not see eye to eye on how to approach a project for an important client. You have tried to discuss it numerous times, but it ends up with each of you sticking firmly to your plan. You have to figure this out soon. The client meeting is now just a couple of days away. | You summarize your colleague’s suggested plan for the project, ensuring to avoid your opinion and stay neutral. You then compare this to your approach. By doing so, you are able to find common ground, remove the conflict from the situation, and move forward with a shared approach. |

| You are a registered early childhood educator and supervisor at a local nursery school. Your staff have identified a child who may require early intervention services, and you need to meet with the parents to share these concerns. | You gather the observations of your staff and summarize them when meeting with the parents. The parents provide their input, and then you neutrally and respectfully summarize what you’ve heard from them. You work collaboratively with them to find common ground on the best steps forward to support their child. |

How to Summarize

You should only summarize after you have engaged actively with an author’s message to ensure that you have an accurate understanding of it. (See Prepare, Pause, and Frame; Skim, Scan, and Use Tools; Situate; and Break Down a Source.)

Summarizing involves

- grasping the core meaning;

- distinguishing between the most and least important ideas;

- explaining the main ideas in your own words accurately, respecting the author’s perspective; and

- omitting your evaluation or opinion.

In academic writing, you may need to write a brief summary of a source, and in other cases, you will write an extended summary.

| Brief Summary | AND/OR | Extended Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Source title, publication details, author’s name, and main idea only | Source title, publication details, author’s name, and main idea | |

| 1–2 sentences in length | Main points in sequential order | |

| Paragraph form with transitions between points to ensure coherence | ||

| Length varies (depending on the length of the original source, but it should be much shorter than the original) |

Tips for summarizing in academic writing include the following:

- write in the present tense;

- acknowledge the source’s title, publication date, and author in the opening of the summary;

- capture the author’s main idea in the opening of the summary, and then summarize the key points in sequential order after that;

- use various verbs to give attribution to the author throughout the summary (see more in How to Give Attribution and Stay Neutral);

- avoid using exact words from the original source unless necessary (avoid looking at the source when summarizing to ensure that your wording is unique);

- be sure to quote (i.e. include content in quotation marks) if it is necessary to use exact words from the source; and

- cite appropriately (see a relevant style guide for various options).

BRIEF SUMMARY

In “It’s Time for ‘They’” published in The New York Times in 2019, author Farhad Manjoo argues that the pronoun ‘they’ should be uniformly used in place of gendered pronouns such as ‘he’ and ‘she.’

EXTENDED SUMMARY

In “It’s Time for ‘They,’” published in The New York Times in 2019, Farhad Manjoo argues that the pronoun ‘they’ should be uniformly used in place of gendered pronouns such as ‘he’ and ‘she.’ Manjoo begins by indicating that people use ‘he’ and ‘him’ when referring to them, and Manjoo accepts this. However, Manjoo comments on issues with assuming gender and asserts that gendered pronouns have limited advantages. Manjoo is confused by the need of some institutions to continue to use gendered pronouns and points out the advantages of uniform use of ‘they.’ Manjoo believes it is inclusive and ubiquitous; this is supported by a study. Manjoo observes that many companies use ‘they’ in marketing and states that only grammarians are recommending against it. Manjoo believes society should avoid gender norms, and that doing so in language is a start. Manjoo concludes with a request that others use the pronoun ‘they’ for both Manjoo and themselves.

This example illustrates how the extended summary can begin with the one-sentence brief summary, which captures the article’s thesis, and then move on to capture the main supporting points provided in the article in sequential order. The extended summary uses citations narratively in each sentence (e.g. “Manjoo comments”; “Manjoo believes”). This is one acceptable way to use citations in a summary according to APA 7 (Walden University, 2020, para. 11). After reading the extended summary, the audience should have a good grasp of Manjoo’s argument.

How to Give Attribution

When you summarize, you must clearly indicate that the ideas you are condensing are not your own; they belong to someone else. This is where author attribution plays a role. Giving author attribution is a key part of ensuring that your summaries have academic integrity.

You are summarizing the main point of “You’ve Got to Find What You Love” by Steve Jobs. You write this:

It’s essential to learn lessons from life experience.

The problem with this is your audience will not know if this is your idea or Steve Jobs’s idea. However, you can fix this by attributing the idea to Jobs. Here is one way you could do this:

Jobs illustrates that it’s essential to learn lessons from life experience.

Notice that the summary of the content is the same (highlighted text), but now this idea is attributed to its author—Steve Jobs—through the use of the lead, “Jobs illustrates that.”

You are a social services worker and have been tasked with summarizing the findings from the report “Ending Mandatory Minimums for Drug Offences.”

You might write this:

Compulsory minimum jail time for drug-related and non-violent offences should be eliminated, giving judges more discretion in sentencing decisions.

There is no attribution for the source of this idea; this means that the reader cannot look up the report to learn more or validate the summary. This undermines the credibility of the summary.

Here is one way to correct this issue:

A report from the Canadian Association of Social Workers (2020) recommends that compulsory minimum jail time for drug-related and non-violent offences should be eliminated, giving judges more discretion in sentencing decisions.

In the correction, there is clear attribution to the author of the report (in this case, the Canadian Association of Social Workers) so that the reader can look up the report to learn more.

You can choose from many verbs to show attribution to the author. These are referred to as signal verbs, and some style guides specify that they should be in the present tense. Here is a helpful list to get you started:

- advises

- asserts

- concludes

- continues

- contradicts

- disagrees

- elaborates

- expands

- illustrates

- points out

- predicts

- states

- supports

For many more signal verbs, see here.

Stay Neutral

Staying neutral in a summary can be tricky because you may have a strong opinion on the source that you are eager to express. However, you need to hold back your opinion at this point since the purpose of a summary is to demonstrate a respectful and thorough understanding of a source’s ideas.

You are summarizing June Callwood’s piece “Forgiveness Story.” You might be tempted to write this:

Callwood illustrates various scenarios for forgiveness, thus engaging the reader in a thoughtful way.

However, when you write “thus engaging the reader in a thoughtful way,” you are no longer offering a neutral view of Callwood’s ideas. Instead, you are layering in your opinion on the piece.

You stay neutral by simply using the first part of this sentence:

Callwood illustrates various scenarios for forgiveness.

You’re summarizing a scientific finding that you read titled “Beets Bleed Red but a Chemistry Tweak Can Create a Blue Hue,” and you write this:

In a significant discovery in the field of food science, scientists discovered that beet juice, which is normally a deep red in colour, can be turned blue by modifying the bonds in the beet pigment (Drahl, 2020).

However, the use of the word “significant” reflects your opinion of this discovery and should be avoided when writing a neutral summary. You can correct this by just omitting that word:

In a discovery in the field of food science, scientists discovered that beet juice, which is normally a deep red in colour, can be turned blue by modifying the bonds in the beet pigment (Drahl, 2020).

Try It!

Directions

- Watch this 3.27 minute TED Talk: “Why 1.5 Billion People Eat with Chopsticks” by Jennifer 8. Lee.

- Practise writing a brief summary of this source. (Tips: Remember to include the source details (citation) as part of the summary and limit your summary to 1–2 sentences.)

- Practise writing an extended summary of this source. (Tips: Include details of the source and its main idea first, use present tense throughout, give attribution to the author, and limit your summary to 100–150 words.)

- Compare your brief and extended summaries with the model.

Model: Brief Summary

In the 2020 TED Talk “Why 1.5 Billion People Eat with Chopsticks,” author and journalist Jennifer 8. Lee informs viewers that there is a rich history to chopsticks and various reasons for today’s widespread use.

Model: Extended Summary

In the 2020 TED Talk “Why 1.5 Billion People Eat with Chopsticks,” author and journalist Jennifer 8. Lee informs viewers that there is a rich history to today’s widespread chopstick use and various reasons for it. She begins by describing how to use chopsticks and the variations of materials that can be used for chopsticks. The author believes that chopsticks are suitable for certain foods and shares that their design varies slightly by country. She describes the transition to chopstick use in the West and comments on the reasons they may have been useful thousands of years ago in the East. The author continues by discussing how chopsticks work well for the small bites of food typical in Asian cooking and that they reflect the communal eating style. She concludes with a legend on chopstick use in heaven versus hell.

In this subtopic, you’ve learned how to summarize a source including

- writing brief summaries;

- developing longer or extended summaries;

- giving attribution to the author; and

- remaining neutral throughout the summary.

Freedman, L. (n.d.). Summarizing. University of Toronto. https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/summarize/

Summarizing. (n.d.). Excelsior Online Reading Lab.

https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/Summarizing2019.pdf

Webster, M. (2017, January 18). How to write an academic summary. Thompson Rivers University. https://inside.tru.ca/2017/01/18/how-to-write-an-academic-summary/

Writing a summary. (n.d.). Las Positas College. http://www.laspositascollege.edu/raw/summaries.php

Callwood, J. (2007, June 12). Forgiveness story. The Walrus. https://thewalrus.ca/forgiveness-story/

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (n.d.). About CASW. https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/about-casw/about-casw

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2020, March). Ending mandatory minimums for drug offences. https://www.casw-acts.ca/sites/default/files/documents/Ending_Mandatory_Minimums_for_Drug_Offences_23.pdf

Dalal, B. (2016, August 30). Paraphrasing and summarizing: Two weapons of solid communication. Forbes India. https://www.forbesindia.com/blog/life/paraphrasing-and-summarising-two-weapons-of-solid-communication/

Drahl, C. (n.d.). https://www.carmendrahl.com/

Drahl, C. (2020, April 3). Beets bleed red but a chemistry tweak can create a blue hue. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/chemistry-tweak-beets-red-juice-create-true-natural-blue-dye

Jobs, S. (2005, June 14). ‘You’ve got to find what you love,’ Jobs says. Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/14/jobs-061505/

Lee, J, 8. (n.d.). http://www.jennifer8lee.com/

Lee, J, 8. (2020, January). Why 1.5 billion people eat with chopsticks [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/jennifer_8_lee_why_1_5_billion_people_eat_with_chopsticks?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Levy, S. (2020, October 1). Steve Jobs. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Steve-Jobs

Manjoo, F. (2019, July 10). It’s time for ‘they.’ The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/pronoun-they-gender.html

Science News. (n.d.). About Science News. https://www.sciencenews.org/about-science-news

Stanford. (2008, March 7). Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford commencement address [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UF8uR6Z6KLc

TED. (n.d.). Our organization. https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). June Rose Callwood. In The Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/June-Rose-Callwood

The New York Times Company. (n.d.). Company. https://www.nytco.com/company/

The New York Times. (n.d.). Farhad Manjoo. https://www.nytimes.com/by/farhad-manjoo

The Walrus. (n.d.). The Walrus is Canada’s conversation. https://thewalrus.ca/about/

University of Illinois Springfield. (n.d.). Signal verbs. https://www.uis.edu/cas/thelearninghub/writing/handouts/grammar-mechanics-and-style/signal-verbs/

Walden University. (n.d.). Using evidence: Citation frequency in summaries. https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/evidence/citations/summaries

Paraphrase

Put an author’s ideas into fresh and unique words but stay true to and respect their meaning. Ensure to give credit to the author.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why paraphrase

- How to paraphrase

- Why cite in a paraphrase

Recall what you know: Like summarizing, paraphrasing is an important skill for effective communication in many contexts. Do you know the similarities and differences between summary and paraphrase? Test your knowledge by dragging the descriptors into the appropriate columns.

Think about this: Think of times when you paraphrase in your day-to-day life—perhaps for professional or personal purposes. How important is it to ensure your paraphrase respects the original message’s meaning? Consider how this is a critical part of developing a paraphrase that has integrity and also supports your credibility as an effective communicator.

Why Paraphrase

When you take someone’s ideas and express them in your words while keeping the same approximate length, you are paraphrasing. You must ensure the meaning is consistent with the original source and avoid layering in your commentary or opinions so that the intention of the author is maintained.